As a student of scripture and her tongues, it has become increasingly frustrating to read “NATO” scholarship with their inability to look beyond the narrow end of their own noses. In my 2024 OCABS paper, I criticized the perennial trend in the reception of scripture that values institutional group-think levied against the outsider, in an attempt to foolishly claim ownership over the logoi of God. To anyone who thinks that God values a particular group, have you not read scripture? Have you not read about the healing of the outsider Na‘aman? Or the repentance of the Ninevites in the book of Jonah? Or the story of the Good Samaritan? The faith of the Roman Centurion which was greater than “all of Israel” according to Jesus? Yes, scripture is full of examples where the sins of the “group” lead God to look “outside” of the group. It’s relentlessly repeated ad nauseam beyond absurdity. It actually starts to make you feel crazy.

I remember my first time reading the Bible from Genesis to Revelation during my freshman year of college and feeling utterly exhausted by the Old Testament. The entire thing, for the most part, was Israel sinning and God punishing them. Reading through the prophets made me feel ill. I’m not kidding. I just wanted it to be over so I could get to the “lighter” New Testament. And then I actually got to the New Testament, and it was just a regurgitation of the Prophets. A trick was played on me. I was at the receiving end of īṣḥāq. The more I revisited scripture the more I understood Paul’s magisterial letter to the Roman world:

Τί οὖν ἐροῦμεν; ὁ νόμος ἁμαρτία; μὴ γένοιτο· ἀλλὰ τὴν ἁμαρτίαν οὐκ ἔγνων εἰ μὴ διὰ νόμου· τήν τε γὰρ ἐπιθυμίαν οὐκ ᾔδειν εἰ μὴ ὁ νόμος ἔλεγεν, οὐκ ἐπιθυμήσεις· ἀφορμὴν δὲ λαβοῦσα ἡ ἁμαρτία διὰ τῆς ἐντολῆς κατειργάσατο ἐν ἐμοὶ πᾶσαν ἐπιθυμίαν· χωρὶς γὰρ νόμου ἁμαρτία νεκρά. ἐγὼ δὲ ἔζων χωρὶς νόμου ποτέ· ἐλθούσης δὲ τῆς ἐντολῆς ἡ ἁμαρτία ἀνέζησεν, ἐγὼ δὲ ἀπέθανον, καὶ εὑρέθη μοι ἡ ἐντολὴ ἡ εἰς ζωήν, αὕτη εἰς θάνατον· ἡ γὰρ ἁμαρτία ἀφορμὴν λαβοῦσα διὰ τῆς ἐντολῆς ἐξηπάτησέ με καὶ διὰ αὐτῆς ἀπέκτεινεν. ὥστε ὁ μὲν νόμος ἅγιος, καὶ ἡ ἐντολὴ ἁγία καὶ δικαία καὶ ἀγαθή. τὸ οὖν ἀγαθὸν ἐμοὶ γέγονε θάνατος; μὴ γένοιτο· ἀλλὰ ἡ ἁμαρτία, ἵνα φανῇ ἁμαρτίᾳ, διὰ τοῦ ἀγαθοῦ μοι κατεργαζομένη θάνατον, ἵνα γένηται καθ᾿ ὑπερβολὴν ἁμαρτωλὸς ἡ ἁμαρτία διὰ τῆς ἐντολῆς.

Οἴδαμεν γὰρ ὅτι ὁ νόμος πνευματικός ἐστιν· ἐγὼ δὲ σαρκικός εἰμι, πεπραμένος ὑπὸ τὴν ἁμαρτίαν. ὃ γὰρ κατεργάζομαι οὐ γινώσκω· οὐ γὰρ ὃ θέλω τοῦτο πράσσω, ἀλλ᾿ ὃ μισῶ τοῦτο ποιῶ. εἰ δὲ ὃ οὐ θέλω τοῦτο ποιῶ, σύμφημι τῷ νόμῳ ὅτι καλός. νυνὶ δὲ οὐκέτι ἐγὼ κατεργάζομαι αὐτό, ἀλλ᾿ ἡ οἰκοῦσα ἐν ἐμοὶ ἁμαρτία. οἶδα γὰρ ὅτι οὐκ οἰκεῖ ἐν ἐμοί, τοῦτ᾿ ἔστιν ἐν τῇ σαρκί μου, ἀγαθόν· τὸ γὰρ θέλειν παράκειταί μοι, τὸ δὲ κατεργάζεσθαι τὸ καλὸν οὐχ εὑρίσκω· οὐ γὰρ ὃ θέλω ποιῶ ἀγαθόν, ἀλλ᾿ ὃ οὐ θέλω κακὸν τοῦτο πράσσω. εἰ δὲ ὃ οὐ θέλω ἐγὼ τοῦτο ποιῶ, οὐκέτι ἐγὼ κατεργάζομαι αὐτό, ἀλλ᾿ ἡ οἰκοῦσα ἐν ἐμοὶ ἁμαρτία.

Eὑρίσκω ἄρα τὸν νόμον τῷ θέλοντι ἐμοὶ ποιεῖν τὸ καλόν, ὅτι ἐμοὶ τὸ κακὸν παράκειται· συνήδομαι γὰρ τῷ νόμῳ τοῦ Θεοῦ κατὰ τὸν ἔσω ἄνθρωπον, βλέπω δὲ ἕτερον νόμον ἐν τοῖς μέλεσί μου ἀντιστρατευόμενον τῷ νόμῳ τοῦ νοός μου καὶ αἰχμαλωτίζοντά με ἐν τῷ νόμῳ τῆς ἁμαρτίας τῷ ὄντι ἐν τοῖς μέλεσί μου. Ταλαίπωρος ἐγὼ ἄνθρωπος! τίς με ῥύσεται ἐκ τοῦ σώματος τοῦ θανάτου τούτου; εὐχαριστῷ τῷ Θεῷ διὰ ᾿Ιησοῦ Χριστοῦ τοῦ Κυρίου ἡμῶν. ἄρα οὖν αὐτὸς ἐγὼ τῷ μὲν νοῒ δουλεύω νόμῳ Θεοῦ, τῇ δὲ σαρκὶ νόμῳ ἁμαρτίας.

What then shall we say? That the law is sin? By no means! Yet if it had not been for the law, I would not have known sin. For I would not have known what it is to covet if the law had not said, “You shall not covet.” But sin, seizing an opportunity through the commandment, produced in me all kinds of covetousness. For apart from the law, sin lies dead. I was once alive apart from the law, but when the commandment came, sin came alive and I died. The very commandment that promised life proved to be death to me. For sin, seizing an opportunity through the commandment, deceived me and through it killed me. So the law is holy, and the commandment is holy and righteous and good. Did that which is good, then, bring death to me? By no means! It was sin, producing death in me through what is good, in order that sin might be shown to be sin, and through the commandment might become sinful beyond measure.

For we know that the law is spiritual, but I am of the flesh, sold under sin. For I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree with the law, that it is good. So now it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me. For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh. For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells within me.

So I find it to be a law that when I want to do right, evil lies close at hand. For I delight in the law of God, in my inner being, but I see in my members another law waging war against the law of my mind and making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death? Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord! So then, I myself serve the law of God with my mind, but with my flesh I serve the law of sin. — Rom. 7:7–25 ESV

Suffice it to say, if you’re reading scripture to justify yourself you are in direct opposition to the Apostle Paul — which is bad news because according to his letter to the Galatians,

Θαυμάζω ὅτι οὕτω ταχέως μετατίθεσθε ἀπὸ τοῦ καλέσαντος ὑμᾶς ἐν χάριτι Χριστοῦ εἰς ἕτερον εὐαγγέλιον, ὃ οὐκ ἔστιν ἄλλο, εἰ μή τινές εἰσιν οἱ ταράσσοντες ὑμᾶς καὶ θέλοντες μεταστρέψαι τὸ εὐαγγέλιον τοῦ Χριστοῦ. ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐὰν ἡμεῖς ἢ ἄγγελος ἐξ οὐρανοῦ εὐαγγελίζηται ὑμῖν παρ᾽ ὃ εὐηγγελισάμεθα ὑμῖν, ἀνάθεμα ἔστω. ὡς προειρήκαμεν, καὶ ἄρτι πάλιν λέγω· εἴ τις ὑμᾶς εὐαγγελίζεται παρ᾽ ὃ παρελάβετε, ἀνάθεμα ἔστω.

I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting him who called you in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel — not that there is another one, but there are some who trouble you and want to distort the gospel of Christ. But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach to you a gospel contrary to the one we preached to you, let him be accursed. As we have said before, so now I say again: If anyone is preaching to you a gospel contrary to the one you received, let him be accursed. — Gal. 1:6–9 ESV

Therefore, it is ridiculous to read scripture as a “Christian” or “Jew” or “secular scholar”. When Paul says καθὼς γέγραπται, he means that scripture was already written before you were born! Who you are is of no importance.

I am using this as a preface because the words I am going to study in this article have been butchered by Jewish, Christian, and secular scholars alike. It all stems from the push to either defend the New Testament (and therefore Christianity) or to disregard it, with the presupposition that Jews inherently have a more authentic understanding of the Hebrew Bible. Unfortunately, modern rabbis (and NATO scholars) read Hebrew as if it is Yiddish — their concocted “Germanic” language — and therefore miss the itinerary of Semitic roots and their functionality. This is put on full display when they make a big deal about the Septuagint’s rendering of עַלְמָה ‘almah into παρθένος parthenos — virgin in Isaiah 7:14 and Matthew’s use of that verse in 1:23. They argue that עַלְמָה “means” young woman, not virgin, and is therefore mistranslated in the Septuagint. With Matthew quoting the mistranslation, he is (in their view) mischaracterizing the prophet Isaiah, ipso facto invalidating the literature of the New Testament.

The issue is that the polemics on either side (pro-Jew vs. pro-Christian) blind both camps from clearly hearing and understanding the words of the Prophet Isaiah on the one hand, and the message of Matthew on the other hand. To hear it, we have to do the work of lexicography.

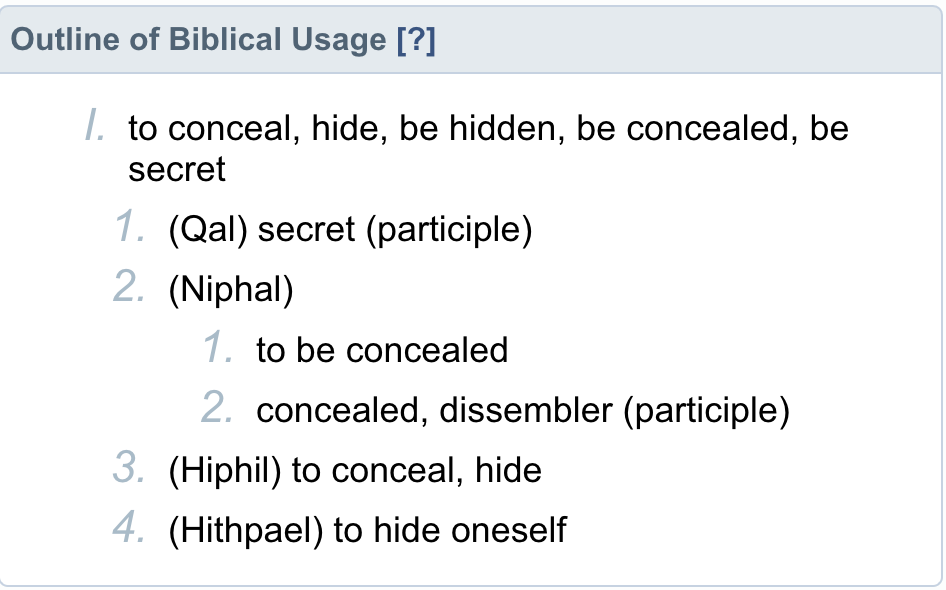

The function עַלְמָה is the feminine form of עֶלֶם ‘elem referring to a young man or a youth. Western dictionaries stop there, to their detriment. The root ‘ayin-lamed-mem in its verbal form is עָלַם ‘alam which properly means to hide or conceal.

It is precisely this connection where the link to the Greek παρθένος is blatantly obvious. A young (hidden/unknown) woman is assumed to be pure (i.e. a virgin). Think of the biblical euphemism for sexual activity: so and so “knew” his wife. This is a cultural image that we can understand in the West. Why is a bride veiled when she is presented to her bridegroom? When a bride is veiled, she is functioning as an ‘almah. In some interpretations of Islamic jurisprudence, unmarried women are expected to wear a face covering until they are married.

At its most basic level, παρθένος refers to being set apart (i.e. taboo/ sacrosanct) thus it renders עַלְמָה beautifully. “Virginity” is certainly implied but not necessarily guaranteed by either word. Fixating on the virginity of the subject also gravely misses the point, and is a clear example of theological discourse ambiguating the text.

So what was Isaiah getting at in chapter 7? Was it his intention to predict a miraculous birth a la Christian theology? No, and neither was Matthew’s.

לָכֵן יִתֵּ֨ן אֲדֹנָ֥י ה֛וּא לָכֶ֖ם אֹ֑ות הִנֵּ֣ה הָעַלְמָ֗ה הָרָה֙ וְיֹלֶ֣דֶת בֵּ֔ן וְקָרָ֥את שְׁמֹ֖ו עִמָּ֥נוּ אֵֽל חֶמְאָ֥ה וּדְבַ֖שׁ יֹאכֵ֑ל לְדַעְתֹּ֛ו מָאֹ֥וס בָּרָ֖ע וּבָחֹ֥ור בַּטֹּֽוב כִּי בְּטֶ֨רֶם יֵדַ֥ע הַנַּ֛עַר מָאֹ֥ס בָּרָ֖ע וּבָחֹ֣ר בַּטֹּ֑וב תֵּעָזֵ֤ב הָאֲדָמָה֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר אַתָּ֣ה קָ֔ץ מִפְּנֵ֖י שְׁנֵ֥י מְלָכֶֽיהָ יָבִ֨יא יְהוָ֜ה עָלֶ֗יךָ וְעַֽל־עַמְּךָ֮ וְעַל־בֵּ֣ית אָבִיךָ֒ יָמִים֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר לֹא־בָ֔אוּ לְמִיֹּ֥ום סוּר־אֶפְרַ֖יִם מֵעַ֣ל יְהוּדָ֑ה אֵ֖ת מֶ֥לֶךְ אַשּֽׁוּר

Therefore the Lord himself will give you a sign. Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel. He shall eat curds and honey when he knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good. For before the boy knows how to refuse the evil and choose the good, the land whose two kings you dread will be deserted. The Lord will bring upon you and upon your people and upon your father’s house such days as have not come since the day that Ephraim departed from Judah — the king of Assyria! — Isa. 7:14–17 ESV

The context of this verse is an ongoing oracle to King Ahaz of Judah, who was a wicked ruler in Jerusalem (2 Kgs 16:2). When the looming threat of the Assyrian Empire was at its most intense, the smaller kingdoms of Syria and Samaria allied to avoid becoming vassal states. Ahaz refused to bring Judah against the Assyrians out of fear, prompting the Syria-Samaria alliance to attack Judah in an attempt to depose Ahaz. As a result, we know from 2 Kings 16 that Ahaz did eventually seek the aid of Tiglath-Pileser III of Assyria, gifting him with gold from the Jerusalem temple. In Isaiah, the prompt from the prophet was to not rely on foreign powers but to be firm in faith (Isa. 7:9). The “prophecy” to Ahaz says that an ‘almah shall bear a son called “God with us”, and before he is old enough to know right from wrong God will devastate both Syria and Samaria (leading to “northern Israel’s total destruction). It’s poetic, saying that the events will take place swiftly. This prophecy comes with a double-edged sword, however. The Assyrians will cause suffering to the Judahites as well, even though Jerusalem itself won’t fall like Samaria until the Babylonian conquest over a century later. The designation “God with us” refers to judgment as it does in the other “child-is-born” prophecies in 8:3 and 9:6.

In the New Testament, the warning to Ahaz becomes the warning to Herod and Rome. The birth of Christ signals the end to both of their exploits, which is why the mighty King Herod loses his mind over a baby in a feeding trough. When a child is born at God’s command, it’s bad news for the ruling powers. THIS is how we should view Matthew’s “fulfillment” of the oracle to Ahaz.

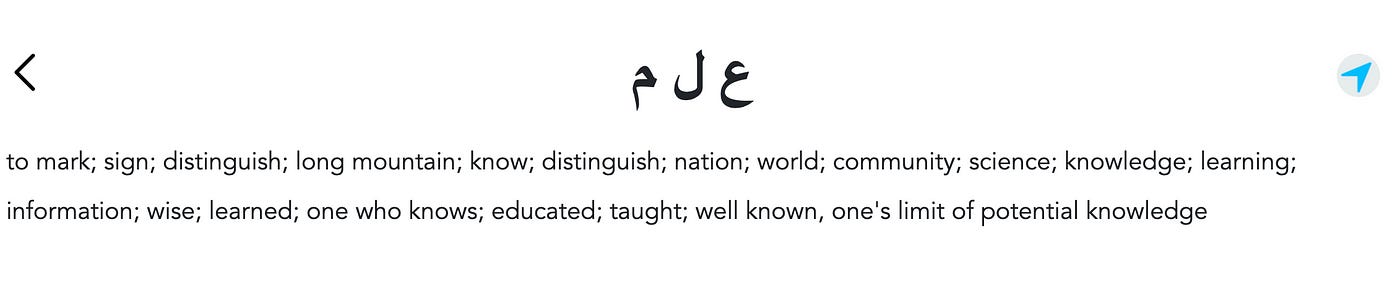

So why use עַלְמָה instead of נַעֲרָה na‘arah — young girl which can refer to a girl up to her teenage years? I think the answer precisely has to do with the function of hiddenness and revelation embedded within the root ‘ayin-lamed-mem. In Arabic, عَلَّمَ ‘alama means “to teach” or reveal. It seems contrary to the Hebrew verb, but for something to be taught, it needs to be hidden (i.e. out of view) first. With relevance to Isaiah, it can also refer to a “sign” and is the root behind the Arabic word for “flag” — علَم ‘elam.

In this way it can be understood to refer to the “world” or “age” because that is where matters are made known.

In Isaiah, the child Immanuel represents God’s judgment that is hidden from Ahaz, and will soon be revealed to him via God’s destruction of Syria and Samaria and the subsequent harsh treatment of Judah by the hand of the Assyrians. In the same way, Mary in Matthew’s Gospel acts as the vessel in which the “mystery which was hidden” was revealed to the world (Col. 1:26–28). Paul often speaks of Christ as a “revealed mystery”. Mary is the ultimate ‘almah.

So what is the difference between עַלְמָה and בְּתוּלָה betulah which is more specifically tied to “virginity” in the contexts in which it is found? Etymologically it doesn’t necessarily have to do with “virginity” per se, but like παρθένος it refers to one being “devoted” or set aside. That is the literal rendering of the root across the Semitic gamut.

Because Greek doesn’t have an exact equivalent to עַלְמָה, it had to settle for a word that was closer to בְּתוּלָה but still got the point across.

In conclusion, the question here has little to do with “literal” virginity — it has to do with God’s mystery being revealed. If virginity matters in the case of Mary, it is only to underscore that Christ is only God’s son and only belongs to Him. That is why Christ came into the world without human effort. God made Mary, his עַלְמָה, pregnant with the one who would one day sit at the right hand of the Father and judge all nations.