Daniel 2:7–8 — Semitic Language Study

עֲנֹ֥ו תִנְיָנ֖וּת וְאָמְרִ֑ין מַלְכָּ֕א חֶלְמָ֛א יֵאמַ֥ר לְעַבְדֹ֖והִי וּפִשְׁרָ֥ה נְהַחֲוֵֽה עָנֵ֤ה מַלְכָּא֙ וְאָמַ֔ר מִן־יַצִּיב֙ יָדַ֣ע אֲנָ֔ה דִּ֥י עִדָּנָ֖א אַנְתּ֣וּן זָבְנִ֑ין כָּל־קֳבֵל֙ דִּ֣י חֲזֵיתֹ֔ון דִּ֥י אַזְדָּ֖א מִנִּ֥י מִלְּתָֽא

They answered a second time and said, “Let the king tell his servants the dream, and we will show its interpretation.” The king answered and said, “I know with certainty that you are trying to gain time, because you see that the word from me is firm.

Notes on Aramaic Grammar

Today’s study will begin with some peculiarities concerning Aramaic grammar since we’ve covered most of the vocabulary included here. Right off the bat, Aramaic uses a ד (dalet) preposition which is unique. This preposition functions as a genitive (possessive) marker but also functions as a preposition of relation. In other words, it can mean “that” or “which”. For an example, let’s take the last sentence from the passage above:

…because (דִּ֣י) you see that (דִּ֣י) the word from me is firm

There, the dalet preposition is functioning in a similar way to the Hebrew prefixes כי and ש and the word אשר all of which can mean “who or that” in different contexts. Another clear example can be seen in the Syriac (a group of Aramaic dialects) translation of the Lord’s Prayer. The opening line is,

ܐܒܘܢ ܕܒܫܡܝܐ abun d’bashmayo — our father who (ܕ) is in heaven.

Here, the ܕ (dalet) preposition is placed before the ܒ (bet) preposition. Delitzsch’s Hebrew translation of the New Testament has אָבִינוּ שֶׁבַּשָׁמַיִם abinu she-bashamayim with the letter ש acting in a very similar way to the ד. By contrast, the common Arabic translation supplies the word الذي alladhi — who/ that.

أبانا الذي في السموات abana alladhi fi’l samawat

This is interestingly comprised of the definite article ال al, the construction لَ la, and ذِي dhi — this/ that which is spoken of in more detail below. The Biblical Hebrew equivalent of this expression is הלזה hallazeh — this which appears in only two places (Gen. 24:56 and Gen. 37:19).

In the genitive sense, we have the sentence שַׁלִּיטָ֣א דִֽי־מַלְכָּ֔א shaliṭā di malkā — captain of the king. By contrast, Hebrew usually communicates the genitive by transforming the noun from its absolute state (as in the plural בָּנִים banim— sons) to its construct state (בְּנֵי bnei). Thus, sons of Israel would be בני ישראל instead of בנים ישראל. Another possible link with Hebrew is the word זֶה zeh — this. The change from the “z” sound to a “d” is not unusual in languages, a prominent example being different forms of the Greek name Ζεύς, which is in the nominative. In the genitive case, it becomes Διός Dios whence we get the Latin Deūs.

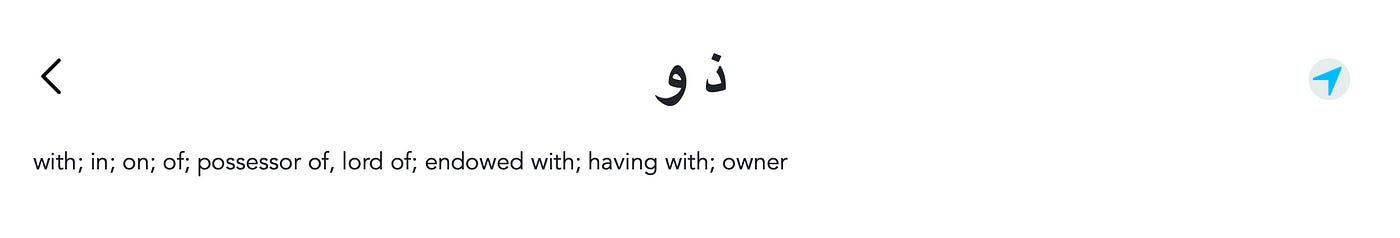

Interestingly, Arabic has both a cognate to the Hebrew זֶה as well as the Aramaic די. The former is the word هذا hadha — this and the latter is the word ذو dhu meaning a “possessor of”. The famous example in the Qur’an is the character ذو القرنين dhu al-qarnayn — possessor of the two horns in 18:83–98. Other examples include ذو النون dhu an-nun — the one with the fish (68:48) and ذو الكف dhu al-kifl — possessor of the portion (21:85, 38:48). Here is the full lexical gloss of ذو in the Qur’an, which appears more than 90 times.

In Arabic, ذو is treated as its own lexical entry rather than as a preposition. This is yet another example of Syriac influence on the language of the Qur’an, especially since the story of dhu al-qarnayn is a reference to Syriac legends about Alexander of Macedon. The “two horns” comes from the book of Daniel (8:3), which was markedly influential among Syriac Christians in the 6th and 7th centuries.

Another interesting feature of Aramaic that sets it apart, is the placement of the definite article (א) as a suffix rather than a prefix. Constructions such as מלכא malka — the king has an aleph at the end of the world, signifying the definite article. This is in contrast to the definite article in Hebrew (ה), used as a prefix. Thus the same construction in Hebrew would be המלך ha-melek. Like Hebrew, Arabic also uses its definite article (ال) as a prefix rather than a suffix. Thus, we would have الملك al-malik in Arabic.

The last note on Aramaic grammar that I would like to make before we cover new vocabulary, is the switch in some cases of the letter שׁ shin to ת taw. This is very similar to the switch from שׁ to ث tha in Arabic. An example from the Aramaic of this section is the word תנינות tinyanut — a second time. In Hebrew, we would have שניות shinyot, and in Arabic it would be ثانية thaniyatun.

New Vocabulary

The word יציב yaṣib is translated as “certainty”. The triliteral connotes something settled, in a fixed position. The verb יצב yaṣab in Hebrew means to take a stand. The Arabic equivalent is وصب waṣaba which means to remain“constant, fixed, or settled”. The next word is עדנא ‘idana — the time from the root עדה ‘adah referring to a fixed period of time. A common word from this root in Hebrew is the construction עד, meaning “until”. Related to this also is the word עֵדָה ‘edah — gathering and in turn, the Arabic عيد ‘eid — feast/ festivalwhich connotes both an appointed time as well as a gathering. Next we have the word זָבְנִ֑ין zabnin from the root זְבַן zeban — to buy/ gain but specifically in the sense of “bargaining in a way that takes advantage”. This sense can be readily seen in the Arabic, where the root زبن zabana typically has the meaning of “pushing” or “thrusting”, but can also have the sense of selling goods at an unfair or dishonest price. Lastly we have חָזָה ḥazah referring to “seeing” or a “vision”. This notion of “seeing” has to do more with perception, rather than just taking in visual stimuli. It is often used with respect to the prophets. The Arabic equivalent is حزو/ حزى ḥaza/ ḥazu — to compute by conjecture/ see in the distance and also can refer to an astronomer.

LXX

’Aπεκρίθησαν δὲ ἐκ δευτέρου λέγοντες Βασιλεῦ, τὸ ὅραμα εἰπόν, καὶ οἱ παῖδές σου κρινοῦσι πρὸς ταῦτα. καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς ὁ βασιλεύς Ἐπ᾽ ἀληθείας οἶδα ὅτι καιρὸν ὑμεῖς ἐξαγοράζετε, καθάπερ ἑωράκατε ὅτι ἀπέστη ἀπ᾽ ἐμοῦ τὸ πρᾶγμα· καθάπερ οὖν προστέταχα, οὕτως ἔσται.

And they answered a second time saying, “o King, the dream spoke and your young ones shall judge according to these”. And the King said to them, “On the truth, I know that you are redeeming the time (as in stalling for time/using it), just as you have seen that the thing has departed from me, so it shall be as I have commanded.

One thing of note in the translation is the rendering of זְבַן to the verb ἐξαγοράζω exagorazō meaing “to redeem”. If זְבַן refers to “taking advantage” of time in the sense of “stalling”, ἐξαγοράζω is a fascinating translation. Because it means to “redeem”, the sense should be more positive in tone. We see this positive use of it twice in the New Testament.

Βλέπετε οὖν πῶς ἀκριβῶς περιπατεῖτε μὴ ὡς ἄσοφοι ἀλλ᾽ ὡς σοφοί, ἐξαγοραζόμενοι τὸν καιρόν ὅτι αἱ ἡμέραι πονηραί εἰσιν.

See then how diligently you walk not as the unwise ones but as the wise ones, redeeming the time because the days are evil. — Eph. 5:15–16

Ἐν σοφίᾳ περιπατεῖτε πρὸς τοὺς ἔξω τὸν καιρὸν ἐξαγοραζόμενοι

In wisdom walk towards those outside, redeeming the time. — Col. 4:5

Here, the sense is of using time wisely. The way that Nebuchadnezzar is delivering it in Daniel, however, is much more negative. It is not so much using time “wisely” as it is stalling for time because they know that his word is firm that he will punish them unto destruction.

The use of τὸ πρᾶγμα pragma — thing is interesting as well in its rendering of מלתא. This word in Aramaic, like its Hebrew counterpart דבר, can refer to either a spoken “word” or the “matter at hand”. It can be translated either way. For example, the Vulgate takes the opposite approach and uses the word sermō — speech/ discourse instead.