Daniel 2:9 — Semitic Language Study

דִּ֣י הֵן־חֶלְמָא֩ לָ֨א תְהֹֽודְעֻנַּ֜נִי חֲדָה־הִ֣יא דָֽתְכֹ֗ון וּמִלָּ֨ה כִדְבָ֤ה וּשְׁחִיתָה֙ הַזְמִנְתּוּן לְמֵאמַ֣ר קָֽדָמַ֔י עַ֛ד דִּ֥י עִדָּנָ֖א יִשְׁתַּנֵּ֑א לָהֵ֗ן חֶלְמָא֙ אֱמַ֣רוּ לִ֔י וְֽאִנְדַּ֕ע דִּ֥י פִשְׁרֵ֖הּ תְּהַחֲוֻנַּֽנִי׃

For if you do not make known to me the dream, this is your one decree: you have agreed to lying and corrupt words to speak before him until this situation be changed. Therefore, tell me the dream and I shall know that you can show me the interpretation.

This week’s study of Daniel will be focused primarily on one word since we’ve already covered most of the vocabulary in this verse. Despite this being nominally a “Semitic language” study, the word we will look at today is actually a borrowed Persian word.

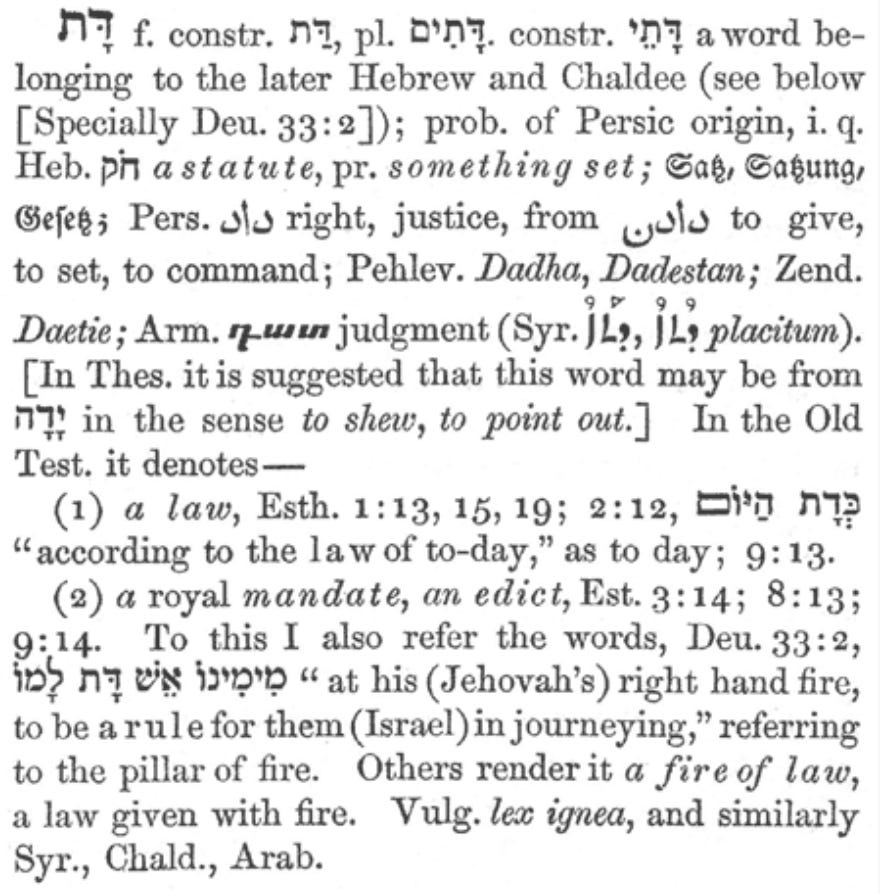

In my translation, the Aramaic דת dat (from דָֽתְכֹ֗ון datkon) is rendered as “decree” but can also be translated to “law” or “regulation”. Here is the entry from Gesenius’ lexicon.

This word should be recognizable by English speakers because it clearly shares an origin with the word “data” which we inherited from Latin. In English, it refers to a recorded observation. In Latin, however, it more readily means something “given” or “provided”. “Data” would actually be the nominative plural form, whereas the lexical form (nom. sg) would be “datum”.

From the Vulgate:

Quare data est misero lux et vita his qui in amaritudine animae sunt

Why is light given (data) to him that is in misery, and life to them that are in bitterness of soul? — Job 3:20

This cognate exists in Sanskrit with दत्त datta — gift/ donation.

From the Bhagavad Gita:

इष्टान्भोगान्हि वो देवा दास्यन्ते यज्ञभाविताः। तैर्दत्तानप्रदायैभ्यो यो भुङ्क्ते स्तेन एव सः ।

The gods, nourished by the sacrifice, will give you the desired objects. So, he who enjoys the objects given (दत्तान् dattan) by the gods without offering anything in return is indeed a thief. — BG 3:12

In Greek, we have the word δότης which refers to a “giver”.

From 2 Corinthians:

ἕκαστος καθὼς προῄρηται τῇ καρδίᾳ, μὴ ἐκ λύπης ἢ ἐξ ἀνάγκης· ἱλαρὸν γὰρ δότην ἀγαπᾷ ὁ Θεός.

Each one as he purposes in the heart, not out of regret or out of necessity: for God loves a cheerful giver (δότην) — 2 Cor. 9:7

Related to the Greek δότης is the word δόσις of a similar, if not identical, function. It’s common in the evolution of languages that the consonants “t” and “s” will merge. For example, the word for “sea” in Koine Greek is θάλασσα but in the Attic dialect, it was written as θάλαττα. It is from δόσις where we get the name Θεοδόσιος theodosios — gift of God. It is roughly analogous to the Hebrew name נְתַנְאֵל or “Nathaniel” in transliteration. It also corresponds to the Arabic name عطالله ‘aṭṭallah. Today, the Greek Orthodox Archbishop of Sebastia (a Palestinian village) bears both the Greek and Arabic forms of this name.

Another form of this name with the words flipped is Δοσίθεος dositheos. A famous bearer of this name was Patriarch Dositheos II of Jerusalem.

Since this word was common in the Persian Empire, it was heavily used in the Aramaic language. In the Aramaic sections of the Old Testament, the word דת is used 14 times. It is used an additional 20 times in the book of Esther which is mostly written in Hebrew, with several “Aramaisms” in the text. It always refers to a royal decree or some legal regulation. Some scholars believe it could also be the source of the word דֹּתָן dotan which is a location mentioned in Genesis and 2 Kings. Vocalized differently, it could be dotayin, the Aramaic dual meaning “two decrees”.

Another disputed instance of this word in the Torah is from the end of Deuteronomy.

וַיֹּאמַ֗ר יְהוָ֞ה מִסִּינַ֥י בָּא֙ וְזָרַ֤ח מִשֵּׂעִיר֙ לָ֔מֹו הֹופִ֙יעַ֙ מֵהַ֣ר פָּארָ֔ן וְאָתָ֖ה מֵרִבְבֹ֣ת קֹ֑דֶשׁ מִֽימִינֹ֕ו אֵשְׁדָּת לָֽמֹו׃

And he said “Yahweh came from Sinai and rose against them from Seir. He shined forth from Mount Paran and he came with ten thousand Holy Ones. From his right hand was a firey decree (אֵשְׁדָּת) for them. — Deut. 33:2

Commentators have long been puzzled by אֵשְׁדָּת eshdat which appears to be a combination of the Hebrew word “fire” and the Aramaic word “decree”. This, along with the place name Dothan, would be the only instances of Persian loanwords (via Aramaic) in the Hebrew Bible. Such instances (as well as other textual evidence) lead most contemporary scholars to date the Pentateuch either in the Persian period (6th to 4th century BCE) or the Hellenistic period (3rd to 2nd century BCE).

These examples are fascinating because they paint scripture as a whole as more of a linguistic tapestry rather than a monolinguistic piece. Of course, the centerpiece is Hebrew, but the scriptures make it clear that Elohim is the god of all people and therefore the ultimate audience of the scriptural message is every nation.

LXX

’Eὰν μὴ τὸ ἐνύπνιον ἀπαγγείλητέ μοι ἐπ᾽ ἀληθείας καὶ τὴν τούτου σύγκρισιν δηλώσητε, θανάτῳ περιπεσεῖσθε· συνείπασθε γὰρ λόγους ψευδεῖς ποιήσασθαι ἐπ᾽ ἐμοῦ, ἕως ἂν ὁ καιρὸς ἀλλοιωθῇ. νῦν οὖν ἐὰν τὸ ῥῆμα εἴπητέ μοι ὃ τὴν νύκτα ἑώρακα, γνώσομαι ὅτι καὶ τὴν τούτου κρίσιν δηλώσητε.

If you do not report the dream to me truthfully and make known its interpretation, you will fall into death; for you have agreed to speak false words before me until the time changes. Now, therefore, if you tell me the matter which I have seen in the night, I will know that you can also make known its judgment.

’Eὰν οὖν τὸ ἐνύπνιον μὴ ἀναγγείλητέ μοι οἶδα ὅτι ῥῆμα ψευδὲς καὶ διεφθαρμένον συνέθεσθε εἰπεῖν ἐνώπιόν μου ἕως οὗ ὁ καιρὸς παρέλθῃ τὸ ἐνύπνιόν μου εἴπατέ μοι καὶ γνώσομαι ὅτι τὴν σύγκρισιν αὐτοῦ ἀναγγελεῖτέ μοι.

If therefore you do not report the dream to me, I know that you have agreed to speak a false and corrupt word before me until the time passes. Tell me the dream, and I will know that you can declare its interpretation to me.

Here, I shared two different Greek translations according to different manuscripts. Neither one renders the sentence declaring Nebuchadnezzar’s decree. While it appears absent in the Septuagint, Jerome includes the sentence in his translation. There he renders it as “una est de vobis sententia”. There he uses the word “sentence” as in a judgment. This is interesting because דת evolved in Jewish parlance to refer to “religion”. In this sense it is closely analogous to the use of the root din in Arabic, which I wrote an article about.

Scholar Abraham Melamed wrote an interesting article about the evolution of דת in Jewish literature, which I will link here.