I have been studying Hebrew and Greek for five years now and this journey has been “staggering” to say the least. I never considered myself much of a language person. Sure, I’ve always been interested in other languages but never made any serious progress in attempting to learn them. During my junior year of college, I remember opening up a Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensiain the library and scanning my eyes up and down the columns of indecipherable block-text, envious of the Rabbis and scholars who could perceive beyond the veil and access the words recorded by the prophets and the scribes of old. I had a newfound zeal for understanding scripture — what it was really saying. Everybody had their opinions on scripture, but I was at a point in my life where I was sick to death of opinions. I specifically lost patience with preachers and teachers who barely engaged with the original languages, only treading that ground through a desultory stroll through a concordance. Rabbis need to learn Hebrew and Imams need to learn Arabic; it is baffling to me that pastors usually don’t even have an intermediate competency in Koine Greek, let alone Hebrew. My adulthood has been entrenched in the postmodern hellscape of the 21st-century West, and the last thing I needed were teachers who preached — not from the Word — but from their eisegetical imaginations.

Then came God’s wonderful providence when my pastor introduced me to the scholarship of the Very Rev. Dr. Paul Nadim Tarazi. I read his magnum opus The Rise of Scripture which was my proper introduction to Hebrew, specifically how the literature of the Old Testament is shaped by it. In short, Tarazi was the first to lay out all of the connections with literary wordplay and the functionality of names. I learned about the connection between the nakedness of Adam and Eve (‘arummim) and the craftiness of the serpent (‘arom), the function of Isaac’s name as “he laughs” (yisḥaq), and the link between womb (reḥem) and mercy (raḥamim). These connections were only possible in the original Hebrew, which triggered something in my brain. I was enamored with the idea of the Semitic trilateral, where consonantal structures accounted for the entire lexicon and large brush strokes of functionality could be inferred for several distinct words and character names. The discovery of new connections kept me engaged, and to this day (five years later), I still get excited when I learn something new. As someone who has always been interested in storytelling and literature, I became even more fascinated by the mechanics of ancient literature. The Old Testament authors crafted Hebrew as a literary language, much like Homeric Greek and Vedic Sanskrit, to tell a story that only they could tell in the language they sculpted for it. This is not, on its own, unusual. Shakespearean English is pretty much in its own category, and no one would seriously propose that a contemporary translation of his work would be authentically Shakespeare. The Globe Theatre would never present Hamlet in 21st century colloquial English. And yet, we treat translations of the Bible (and other ancient literature) as replacements for the real things. Obviously, people don’t usually say that outright, but we insist that the ESV and KJV are “scripture”. They are helpful roadmaps to scripture, but they are not scripture itself. How could they be? Every translation is an interpretation. The translators behind the Septuagint understood this, as made evident by the prologue to Sirach:

παρακέκλησθε οὖν μετ᾿ εὐνοίας καὶ προσοχῆς τὴν ἀνάγνωσιν ποιεῖσθαι καὶ συγγνώμην ἔχειν ἐφ᾿ οἷς ἂν δοκῶμεν τῶν κατὰ τὴν ἑρμηνείαν πεφιλοπονημένων τισὶ τῶν λέξεων ἀδυναμεῖν· οὐ γὰρ ἰσοδυναμεῖ αὐτὰ ἐν ἑαυτοῖς ἑβραϊστὶ λεγόμενα καὶ ὅταν μεταχθῇ εἰς ἑτέραν γλῶσσαν. οὐ μόνον δὲ ταῦτα, ἀλλὰ καὶ αὐτὸς ὁ νόμος καὶ αἱ προφητεῖαι καὶ τὰ λοιπὰ τῶν βιβλίων οὐ μικρὰν ἔχει τὴν διαφορὰν ἐν ἑαυτοῖς λεγόμενα.

Wherefore let me intreat you to read it with favour and attention, and to pardon us, wherein we may seem to come short of some words, which we have laboured to interpret. For the same things uttered in Hebrew, and translated into another tongue, have not the same force in them: and not only these things, but the law itself, and the prophets, and the rest of the books, have no small difference, when they are spoken in their own language.

This is so critical, because for the translator of Sirach, Greek is functioning here as an introduction to Hebrew. It is not an endgame in and of itself. The goal is to eventually graduate to the Hebrew language. The Greek hearer is instantly told that what they are hearing is unreliable in translation: οὐ μικρὰν ἔχει τὴν διαφορὰν — it has no small difference! So when the hearer is told of σοφία in the book of Sirach, he is not to think of Hellenic “wisdom” traditions but the Hebrew חכמה ḥokmah which is routinely tied to the utterance of the scriptural God:

ΠΑΣΑ σοφία παρὰ Κυρίου καὶ μετ᾿ αὐτοῦ ἐστιν εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα.

All wisdom is from the Lord and with him it remains forever. — Sir. 1:1

God is the sole reference for wisdom. This wisdom then speaks in the first person, saying:

’Eγὼ ἀπὸ στόματος ῾Υψίστου ἐξῆλθον, καὶ ὡς ὁμίχλη κατεκάλυψα γῆν

I went out from the mouth of the most high, and covered the earth as a cloud. — Sir. 24:3

One of the church fathers who really understood this critical importance of Hebrew was St. Jerome. In Greek, his name Ἱερώνυμος means “sacred name” which really fit his career as he labored intensely for the elucidation and instruction of the “sacred language”. In fact, Jerome coined the phrase Hebraica Veritas, which expressed that the original Hebrew texts of the Old Testament (as opposed to the Greek Septuagint) contained the most authentic and authoritative presentation of the scriptures. Jerome emphasized translating directly from the Hebrew rather than relying on the Greek translation, which was pretty much the only widely accessible option in the Roman world at the time.

Recognizing Jerome’s seriousness and zeal for languages, Pope Damasus I personally employed him as his personal secretary in Rome and eventually commissioned him to update the faulty Latin translations of scripture that were available at that time. Damasus knew that Jerome had previously spent time in Palestine learning Hebrew directly from the Jewish community — to my knowledge, he and Origen were the only two of the early church theologians to do this. The only other contender in that area is St. Epiphanius of Salamis, but there is some evidence that he grew up Jewish and converted to Christianity sometime in his early adulthood, so his knowledge of Hebrew was more circumstantial. Jerome was from the region of modern day Croatia in Eastern Europe. This is a man who traveled across the mediterranean to study a “barbarian” language, even though he was trained in and excelled at Ciceronian rhetoric. He was a full fledged Latin, Roman to his very core, and yet he understood the warning of Sirach’s prologue. During Pope Damasus’s lifetime, he was able to complete the Vulgate editions of the Gospels and the Psalms since they were the most commonly used in the church’s liturgical life.

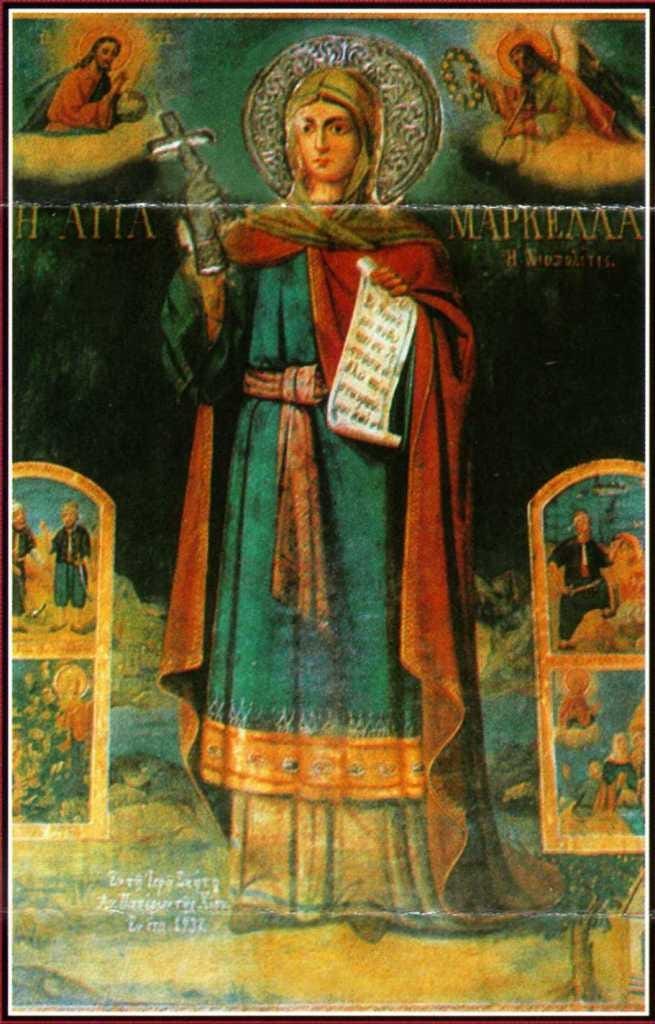

While in Rome, Jerome became acquainted with two recent widows: Marcella and Paula who eventually studied Hebrew under his tutelage. After the Pope’s death in 384, Jerome once again went to Palestine, this time with Paula — Marcella stayed behind to care for the poor in Rome. Paula and Jerome settled in Bethleḥem near the Church of the Nativity and built a small monastery there. She also aided him in the completion of the Vulgate, which went on to be upheld as the favored edition of the biblical text in the Roman Catholic Church up until the liturgical reforms of the 1960s and 70s.

Jerome holds a special place in my heart as I continue in my studies of Hebrew (and now, Arabic). His zeal for Hebraica Veritas is at the heart of what the Palm Tree Initiative is doing in the field of lexicography. All of my articles have been essentially me unpacking what I have learned from Fr. Paul Tarazi and Fr. Marc Boulos — both of whom have completely opened the pages of the biblical text for me. After five years, Hebrew is no longer inaccessible. I can read it, I can analyze it. I have a grasp on the grammar and can parse my way through difficult passages. It’s not impossible, as I had once assumed. And still, Jerome had it way harder. He had to learn Hebrew without modern grammar books, and without the vowel pointings introduced by the Masoretes. He had to learn the naked consonantal text, and submit to the non-Christian barbarian Rabbi in humility for the untranslated words of the prophets to hit his ears and sink into his heart. If he, nearly alone in his generation, could do it — what’s our excuse?

Written (incidentally) for the feast day of St. Marcella of Rome (January 31)

Excellent article! (Although I wouldn't want those who came to a similar love for language after having a few children to feel "less than" for not having as much time to acquire proficiency quite so rapidly. You've worked intensely hard in such a relatively brief span of years!). For all the credit due Jerome for the importance of relying on the "Hebraica Veritas," he nevertheless remained tainted with the cultural heritage of the Greeks. In Genesis 3:16 of the Vulgata, for example, Jerome has no dog in the fight for retaining issabonek ve-heronek as "your sorrow and your conceptions" (aerumnas tuas et conceptus tuos) in contrast to pain in giving birth, but apparently was loathe to render the Hebrew teshuqa as "desire" or "longing for" (cf. Gen 4:7; Song of Songs 7:10), opting rather for the removal of the woman's agency by placing her under the direct power of her husband (et sub viri potestate eris et ipse dominabitur tui). This raises a grammatical disjunction which Jerome seems to want to solve by ignoring the teshuqah and doubling down on the yimshal, but it makes more sense to consider less autocratic renderings of mashal as direct rule (again, cf. Gen. 4:7) to make it more consistent with teshuqah. In sum, Jerome appears to succumb to the persistence of hellenistic modes of thinking vis-a-vis women and misses an opportunity to retain the Hebrew Bible's positive regard toward (non-urban and less misogynistic) labor intensive pastoral and semi-pastoral societies. Keep up the excellent work! I truly enjoy your posts.