This post is a long overdue follow-up to my original study on the word λόγος in the New Testament, as well as its Latin cognate “lex” and the original Hebrew דבר. There is a trend in biblical studies to isolate the use of λόγος in the prologue of John’s gospel, often tying it in with trends in Greek philosophy where this lexical function was the compendium of Aristotle’s categorical reason, which undergirded reality. This was borrowed from the meditations of Heraclitus, who first introduced this notion via the relationship to its verbal counterpart, λέγω legō, which originally meant “to gather, organize, or choose”. It could thus be understood as “natural law” or “reason” as an abstract function. The Stoic philosophers expanded the understanding of λόγος as a causative principle in the universe with the concept of λόγος σπερματικός logos spermatikos, which Philo of Alexandria scandalously imposed on the function of דבר יהוה dabar yahweh in Hebrew. Philo, like Flavius Josephus after him, tried desperately to rebrand the Holy Scriptures into something that the Hellenized Romans could “respect”.

His modus operandi becomes clear in the context of his visit with Caligula in Rome, in an attempt to secure protection for Jews in Alexandria. Instead of functioning as a prophet and sowing the seed blindly, he tried to control the situation by emptying the words of all their power (cf 1 Cor. 1:17). In so doing, he warped scripture into making it appear like Plato’s Timaeus, where the דבר יהוה was cast as the Demiurge of the physical realm. Plato imagined that a mechanism, for which he used the metaphor of a public worker, δημιουργός dēmiourgos, crafted the physical world using the forms/ideas (ἰδέαι) as the blueprint. The Demiurge was not a form in and of itself, but functioned as a receptacle for the forms to come into reality. This distinction between the transcendental “good” and the creative demiurge effectively introduced two “divinites” in the context of Philo’s presentation. There was “God” and an emanation from him, who Philo called the θεὸς δεύτερος theos devteros — second god. The damage that this kind of work did is nearly impossible to do justice to in explaining. It fueled centuries of gnostic philosophies, fueled heresies such as that of Arius, and kick-started the lofty school of Alexandria, which prioritized metaphysical speculation over the functionality of the written text. In fact, the founding of the Antiochian school was largely conceived of in opposition to the philosophical shenanigans of the Alexandrians.

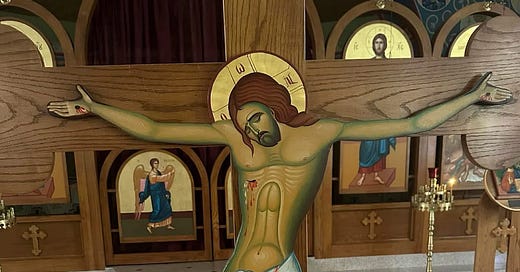

It was this kind of emanation theology that gave rise to the mystical schools of Neo-Platonism, wherein a dedicated practitioner could become divine through ascetic participation. The Alexandrians were all too happy to adopt this practice, with the concept of theosis and Athanasius’s teaching that the essential mission of the incarnate Christ was to make man “divine”. This is nothing other than human aggrandizement, not to mention being also the crimson sin that got Adam and Eve kicked out of the garden! How could the mission of Christ, who did not consider equality with God a thing to be seized, be a means by which man could seize divinity? Sure, Paul speaks about being conformed to the image of Christ in his letter to the Romans (8:29), but this image is the shameful one of Christ crucified (Gal. 2:20, Rom. 6:8–11), not the self-aggrandizing θεὸς δεύτερος! God forbid. “Take up your cross and follow me”, says Jesus, not “take up divinity”. And before any children of Alexandria think that 2 Peter 1:4 encourages their harlotry, they should be reminded that θείας κοινωνοὶ φύσεως theias koinōnoi physeōs —participants of the divine nature is contrasted with ἐν τῷ κόσμῳ ἐν ἐπιθυμίᾳ φθορᾶς en tō kosmō en epithymia phthoras — decay in the world because of lust. In other words, it is reworking Paul’s comments in 1 Corinthians, that the wisdom he is preaching is not that of the rulers of the world that are “coming to naught” (2:6). The content (i.e. word/ logos) of Christ’s shameful death is “eternal life”, not the so-called wisdom of the Greco-Roman world which has no business in being conflated with the the divine utterance. Instead of embracing the shame of the prophets on account of the דבר יהוה (see Isaiah 20:2–4, Jeremiah 20:7–10, and Ezekiel 4:1–17), Philo covered up those dark sayings by dressing them in Hellenistic excess. He turned the literature of the shame of Israel and Judah’s harlotry into a mechanism for mental masturbation. It’s the same impulse that led the Alexandrian theologians to turn the shameful cross of discontrol into a mechanism for human-divine empowerment. How sinister is that? They sold the farm in the name of PR, because the actual teachings of Paul and the prophets before him are so difficult and against the grain of human pride that to faithfully walk in the statutes of the lord is to actually die to oneself and take up a banner of shame. “Can you drink the cup that I drink, or be baptized in the baptism I am baptized with?” — Jesus rhetorically asks his apostles. They did not know what they were asking for. Who wants that message? Certainly not the Corinthians… nor the Alexandrians apparently, because they taught that the cross was an invitation to become God! Only philosophers could take a teaching of God’s glory through man’s weakness, and warp it into a teaching of man’s glory through God’s weakness (ever hear of kenotic theology?). If you read Philippians 2:7 in the context of Isaiah 53:12, the meaning becomes perfectly clear. The suffering servant made himself naked ערה ‘arah unto death. It’s about accepting shame and cancellation, not about “divine condescension”. Given this perennial trend by theologians, it’s no wonder that scholars have followed them in the same shallow pursuit to cast the λόγος of John’s Gospel in the context of first-century Hellenism, rather than recognizing the fact that λόγος was already established technical terminology from Paul’s letters. In fact, Paul is hardly (if ever) mentioned in commentaries on John 1. The only scholar that I know of who has actually made this seemingly obvious connection is Fr. Paul Tarazi (see his four-part NT introduction series). Unlike John, no one would (at least seriously) argue that Paul’s λόγος (shorthand for the Gospel message of the cross) is synonymous with the Greek philosophical λόγος. This is because Paul directly dismantles that idea in 1 Corinthians.

Οὐ γὰρ ἀπέστειλέν με χριστὸς βαπτίζειν, ἀλλ’ εὐαγγελίζεσθαι· οὐκ ἐν σοφίᾳ λόγου, ἵνα μὴ κενωθῇ ὁ σταυρὸς τοῦ χριστοῦ

For Christ did not send me to baptize but to proclaim the Gospel: not in the wisdom of word (λόγου), so that the cross of Christ might not be emptied. — 1 Cor. 1:17

And right after this, he says:

Ὁ λόγος γὰρ ὁ τοῦ σταυροῦ τοῖς μὲν ἀπολλυμένοις μωρία ἐστίν, τοῖς δὲ σῳζομένοις ἡμῖν δύναμις θεοῦ ἐστιν

For the word (λόγος) of the cross, to those who are perishing, is moronic, but to we who are being saved, it is the power of God. — 1 Cor. 1:18

And later he says:

Κἀγὼ ἐλθὼν πρὸς ὑμᾶς, ἀδελφοί, ἦλθον οὐ καθ’ ὑπεροχὴν λόγου ἢ σοφίας καταγγέλλων ὑμῖν τὸ μαρτύριον τοῦ θεοῦ. Οὐ γὰρ ἔκρινα τοῦ εἰδέναι τι ἐν ὑμῖν, εἰ μὴ Ἰησοῦν χριστόν, καὶ τοῦτον ἐσταυρωμένον

And I brothers, coming to you, did not come according to excellency of word (λόγου) or wisdom, proclaiming to you the testimony of God. For I judged not to know anything before you, except Jesus Christ, and this one crucified! — 1 Cor. 2:1–2

How startling it is that Paul, in only a few strokes of the pen, says on the one hand that his Gospel message is not λόγος but at the same time can speak of the λόγος of the Cross! He ties it all together with:

Καὶ ὁ λόγος μου καὶ τὸ κήρυγμά μου οὐκ ἐν πειθοῖς ἀνθρωπίνης σοφίας λόγοις, ἀλλ’ ἐν ἀποδείξει πνεύματος καὶ δυνάμεως

And my word (λόγος) and my preaching are not in persuasive words of wisdom, but in the demonstration of the spirit and power. — 1 Cor. 2:4

So Paul does indeed carry a λόγος, but one that is expressed in the shame of the crucifixion. That is why it is moronic to those who are perishing, ie, those who are still putting their trust in things that will pass away. For Paul, the λόγος is nothing more than the cross, and by extension, the Old Testament teaching of God cancelling out his prophet. This use of Pauline technical terminology is further made clear when he notes in the aforementioned verse 1:17, that the cross can indeed be “emptied” if Paul were to present his λόγος as one of worldly (that is, Hellenistic) σοφίᾳ. If it can be emptied, that means that the cross itself has “contents”, that being the teaching of its significance. Therefore, Paul established λόγος as shorthandfor Christ crucified! What is further startling is that while the cross (that is, the λόγος of the cross) cannot be emptied, Christ himself needed to be:

ὃς ἐν μορφῇ θεοῦ ὑπάρχων, οὐχ ἁρπαγμὸν ἡγήσατο τὸ εἴναι ἴσα θεῷ, ἀλλ’ ἑαυτὸν ἐκένωσεν, μορφὴν δούλου λαβών, ἐν ὁμοιώματι ἀνθρώπων γενόμενος·

He, being God’s representative, did not consider equality with God a thing to be seized, but emptied himself, taking the representation of a slave, being made in the likeness of men — Phil. 2:6–7

So if Christ is emptied (ἐκένωσεν) and the λόγος is not, then it is inaccurate to say Christ himself is the λόγος of Paul’s preaching. It is rather Christ crucified that is the λόγος, not a preexisting Hellenistic embodiment of order and reason! That is because Christ is a functional literary character whose narrative end (τέλος) is to be put to the shameful death on the cross. Christ says as much in the Gospel of John when he says τετέλεσται tetelestai — it is finished at his last breath. The λόγος cannot be personified in the way that theologians, starting with Philo of Alexandria, do. Paul understood that, which influenced his literature in several key ways.

Knowing, then, that Christ is a character with a narrative end, Paul fleshed out what he meant by I judged not to know anything before you, except Jesus Christ, and this one crucified in his letters, where he treats Christ’s narrative end in the same way that Heraclitus treated the λόγος. For example, later in 1 Corinthians, he writes:

ἀλλ’ ἡμῖν εἷς θεὸς ὁ πατήρ, ἐξ οὗ τὰ πάντα, καὶ ἡμεῖς εἰς αὐτόν· καὶ εἷς κύριος Ἰησοῦς χριστός, δι’ οὗ τὰ πάντα, καὶ ἡμεῖς δι’ αὐτοῦ

But to us there is one God the Father, from whom are all things, and we unto him: and one Lord Jesus Christ, through whom are all things, and we through him. — 1 Cor. 8:6

In other words, because Paul already established that he knew nothing before the Corinthians except the crucified Christ, he presents the Lord Jesus Christ as permeating all of reality. Christ crucified is logic and reason and wisdom according to Paul. In Colossians, he takes it a step further:

ὅς ἐστιν εἰκὼν τοῦ θεοῦ τοῦ ἀοράτου, πρωτότοκος πάσης κτίσεως· ὅτι ἐν αὐτῷ ἐκτίσθη τὰ πάντα, τὰ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς καὶ τὰ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς, τὰ ὁρατὰ καὶ τὰ ἀόρατα, εἴτε θρόνοι, εἴτε κυριότητες, εἴτε ἀρχαί, εἴτε ἐξουσίαι· τὰ πάντα δι’ αὐτοῦ καὶ εἰς αὐτὸν ἔκτισται· καὶ αὐτός ἐστιν πρὸ πάντων, καὶ τὰ πάντα ἐν αὐτῷ συνέστηκεν

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation, in whom all things were created: everything in the heavens and on the earth, the seen and the unseen, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or rulers, or authorities. All things were created through him and in him, and he is before all, and all things hold together in him. — Col. 1:15–17

This is classic Greek philosophical lingo, but with a twist! Paul is being very sneaky here. He is not linking Christ with the Greek philosophical λόγος as is made clear in 2:8, but undermining Hellenism by replacing their concept of reason with the foolishness of the crucified Christ. In other words, he is using the language of the Greco-Romans against them! In this sense, he follows in the footsteps of the author of Sirach, who informs the Greek reader that he or she cannot trust the rendering of the words according to their conventional use in native Greek. This is because scriptural vocabulary is natively Hebrew, and by extension, native to the Hebrew scriptures. Therefore, when words like σοφία show up in the text, the Greek cannot assume he knows what that word means. He is thereby invited to the Hebrew text, where he can discover the wisdom literature in the Ketubim that directly ties σοφία with the Tōrah.

Logos in Mark, Luke, & John

Following the Pauline kerygma, the Gospels continued to challenge the Greco-Roman λόγος with the proclamation of Christ crucified. Since John typically oversaturates the conversation, I will turn first to an interesting passage found in Mark’s Gospel and then repeated in Luke (8:30). This story concerns Jesus’ interaction with the man possessed by a series of demons collectively called “legion”, which is clearly tied to the Roman Legiō. It was so called because it derives from the verb legō in Latin, which shares a cognate with the Greek λέγω and actually preserves the more conservative rendering of that verb as “to choose/ gather”. The “Legiō” got its name because officers in the group were conscripted, and therefore selected and gathered for the job. They also functioned as “law enforcement”, and therefore, were custodes lēgis (custodians of the law). As its genitive form would suggest, the word lex (law) is also from the verb legō. This is interesting because “law” presupposes control, and the ones who control/ enforce that law are the Legiō. So why is this tied with demonic activity in the Gospels? The answer is multifaceted but has to do with a few items. One, it is a reference to Paul’s letter to the Romans, which undercut Roman sensibilities of lex/νόμος in the same way that his letter to the Corinthians undercut Greek sensibilities of σοφία. One needs only to read Romans 12:14–13:7 to understand how he flips Roman authority on its head! Christ, the crucified barbarian, is Dominūs Servī Paulī (Master of the Slave Paul), and the unseen Deūs Christī Barbarī (God of the Barbarian Christ) holds authority over Caesar! Therefore, just as Christ-crucified replaces the Greek λόγος, Christ-crucified likewise replaces the Roman lex. Therefore the Roman Legiō, being the custodians of Roman law, have to be excised from the Roman citizen who accepts the Gospel.

The second reason is that unclean spirits are shorthand for impure teachings that pollute the One Gospel and impede its proclamation. I have spoken on the link between the spirit and teaching before, but it bears repeating. This connection can be clearly seen in Paul’s distinction between the one who is ψυχικός psychikos — natural and πνευματικός pnevmatikos — spiritual, in that the spiritual individual is one who is taught by the spirit, as opposed to following his own breathing (ψυχούμενος). Likewise, scripture charges its hearers to test all spirits (1 Jn. 4:1) to see what they teach. That is why false teachings manifest themselves as unclean, demonic spirits in the Gospel accounts.

Going back to Legion, I think there is interesting word play being employed by the author of Mark’s Gospel (and then repeated by his successors). This is only detectable when we read it in Greek:

Καὶ ἐπηρώτα αὐτόν, Tί σοι ὄνομα; Καὶ ἀπεκρίθη, λέγων, Λεγεὼν ὄνομά μοι, ὅτι πολλοί ἐσμεν

And he (Jesus) asked him, ‘What is your name?’ and he answered saying, ‘Legion is my name, because we are many’ — Mk. 5:9

Now, before I continue, it is worth noting that there are some variations on this passage in the different manuscript traditions. Some of the older, Alexandrian/ Critical manuscripts have καὶ λέγει αὐτῷ Λεγιὼν ὄνομά μοι instead of Καὶ ἀπεκρίθη, λέγων, Λεγεὼν ὄνομά μοι. Regardless of this difference, however, my point still stands because it rests on the closeness of λέγει/λέγων and Λεγιὼν/Λεγεὼν. The Byzantine/ Majority text is more striking because the only difference between the Greek participle λέγων (saying) and the transliteration of the Latin Λεγεὼν (Legion) is the extra epsilon. Other than that, the constructions are nearly identical. I feel as if this can’t be a coincidence. In Greek, Λεγεὼν sounds like a corrupted way to say “of sayings”, especially after λέγων. The plurality of Legion can be detected in the common genitive plural ending ὼν, and it could signify both how power in Rome comes from many sources, and how the false “sayings” are plentious. By contrast, there is only one true Gospel that Paul preaches and therefore, only one λόγος. If Mark is dealing with both lex and λόγος in the pericope of Λεγεὼν, then he is cleverly linking Romans and 1 Corinthians together in one fell swoop! In other words, he’s tackling both conventional Roman law and Greco-Roman philosophy in the same character(s). There is not Λεγεὼν in plurality but a λόγος in unity.

Another important point is that the Λεγεὼν, being Roman law enforcement, wielded the “fear of death” in their dominion. The res publica (i.e., the citizenry) was at their mercy. Even more so were the non-citizens, like Jesus himself, who could be subject to the worst kinds of tortures as an example not to challenge Roman authority.

And before we get to John, it is important to note that Luke’s Gospel already incorporates Paul’s λόγος in its introduction:

Ἐπειδήπερ πολλοὶ ἐπεχείρησαν ἀνατάξασθαι διήγησιν περὶ τῶν πεπληροφορημένων ἐν ἡμῖν πραγμάτων, καθὼς παρέδοσαν ἡμῖν οἱ ἀπ’ ἀρχῆς αὐτόπται καὶ ὑπηρέται γενόμενοι τοῦ λόγου…

Inasmuch as many have attempted to draw up a narrative concerning the things that have been accomplished among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who were eyewitnesses from the beginning, and having become ministers (ὑπηρέται) of the word (λόγου)… — Lk. 1:1–2

This construction ὑπηρέται τοῦ λόγου (ministers of the word) is right out of 1 Corinthians:

Οὕτως ἡμᾶς λογιζέσθω ἄνθρωπος, ὡς ὑπηρέτας χριστοῦ καὶ οἰκονόμους μυστηρίων θεοῦ

Thus a man should regard us, as ministers (ὑπηρέτας) of Christ and stewards of the mysteries of God. — 1 Cor. 4:1

There, Luke is substituting Christ for λόγος… In doing so, he is clearly following Paul’s lead in tying λόγος with the message of Christ crucified. To be a minister of the word in this context is to be an evangelist, and to be an evangelist is to proclaim the Lord’s death as all four Gospels have their climax in the crucifixion of Christ.

Having that background in mind, we can now proceed to John’s Gospel where we majestically hear:

Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος. Οὗτος ἦν ἐν ἀρχῇ πρὸς τὸν θεόν. Πάντα δι’ αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο, καὶ χωρὶς αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο οὐδὲ ἓν ὃ γέγονεν.

In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and the word was God. This one was in the beginning with God. All things came to be through him, and without him, nothing came to be that has come into being. — Jn. 1:1–3

Doesn’t this sound familiar? This is precisely drawing on Paul’s afore-quoted letter to the Colossians! Let’s hear it again:

ὅς ἐστιν εἰκὼν τοῦ θεοῦ τοῦ ἀοράτου, πρωτότοκος πάσης κτίσεως· ὅτι ἐν αὐτῷ ἐκτίσθη τὰ πάντα, τὰ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς καὶ τὰ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς, τὰ ὁρατὰ καὶ τὰ ἀόρατα, εἴτε θρόνοι, εἴτε κυριότητες, εἴτε ἀρχαί, εἴτε ἐξουσίαι· τὰ πάντα δι’ αὐτοῦ καὶ εἰς αὐτὸν ἔκτισται· καὶ αὐτός ἐστιν πρὸ πάντων, καὶ τὰ πάντα ἐν αὐτῷ συνέστηκεν

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation, in whom all things were created: everything in the heavens and on the earth, the seen and the unseen, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or rulers, or authorities. All things were created through him and in him, and he is before all, and all things hold together in him. — Col. 1:15–17

It is the λόγος of the cross that is presented as holding the cosmos together for Paul. In saying so, Paul is not making metaphysical claims, but is using Greek philosophical lingo as a rhetorical device to preach the crucified Christ! It is not man’s wisdom or reason, it is God’s wisdom that is embodied in the crucified locum tenens. This can only be applied to Christ insofar as it is applied to his narrative end. In order to hear what Paul and John are saying, one needs to dispel the notion of the Biblical λόγος as having anything to do with its usage in Hellenistic philosophy, and instead tie it back to Paul’s preaching which usurped both Roman legal customs and Greco-Roman philosophy in a way that demonstrated God’s glory in the crucifixion of the Son of Man! This is the λόγος of John! This is not “high Christology”… this is a repackaging of the prophetic witness of the Old Testament for Paul’s specific Sitz im Leben. This can also be seen in how John’s wording reflects Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians:

Ἐν τῷ κόσμῳ ἦν, καὶ ὁ κόσμος δι’ αὐτοῦ ἐγένετο, καὶ ὁ κόσμος αὐτὸν οὐκ ἔγνω. Εἰς τὰ ἴδια ἦλθεν, καὶ οἱ ἴδιοι αὐτὸν οὐ παρέλαβον

He was in the world, and the world came to be through him, and the world did not know him. He came unto his own, and is own did not receive him — Jn. 1:11–12

Compare with:

ἀλλὰ λαλοῦμεν σοφίαν θεοῦ ἐν μυστηρίῳ, τὴν ἀποκεκρυμμένην, ἣν προώρισεν ὁ θεὸς πρὸ τῶν αἰώνων εἰς δόξαν ἡμῶν· ἣν οὐδεὶς τῶν ἀρχόντων τοῦ αἰῶνος τούτου ἔγνωκεν· εἰ γὰρ ἔγνωσαν, οὐκ ἂν τὸν κύριον τῆς δόξης ἐσταύρωσαν

But we speak the hidden wisdom of God in a mystery, which God foreordained before the ages unto our glory. None of the rulers of this age knew it. For if they knew, they would not have crucified the Lord of Glory! — 1 Cor. 2:7–8

This “hidden wisdom” Paul speaks of is a reference to the mechanism in the Wisdom Literature of the Old Testament, which supplanted Greek σοφία with the Tōrahic instruction (cf. Proverbs 8). This is also the λόγος that comes enfleshed and “camped” among the apostles!

Καὶ ὁ λόγος σὰρξ ἐγένετο, καὶ ἐσκήνωσεν ἐν ἡμῖν― καὶ ἐθεασάμεθα τὴν δόξαν αὐτοῦ, δόξαν ὡς μονογενοῦς παρὰ πατρός― πλήρης χάριτος καὶ ἀληθείας

And the word became flesh, and camped among us — and we beheld his glory, glory as the only begotten from the Father — full of grace and truth. — Jn. 1:14

The arrival of the λόγος enfleshed in God’s representative is paramount for the teaching of the crucifixion of the flesh. It all works together. That is why early Christians like Ignatius of Antioch took the reality of the “enfleshed Christ” so seriously. For the Gospel to have its power, the Son of Man needs to be put down and reduced to nothing. Only then can God’s glory shine over all authorities when he raises that crushed servant, despised by the world, and sets him at his right hand to judge all nations at the end of the ages. That is the power of the resurrection. God made his locum tenens stand! The lowly barbarian Jesus, who was reduced to nothing by the Λεγεὼν, is set up by his Father and momentarily wields his authority.

We adore his third day resurrection.

Christ is Risen!

Blessed Pascha to all nations. Let us enjoy the feast whether we fasted or not. The Lord of Glory has trampled down death by death.

Amen.