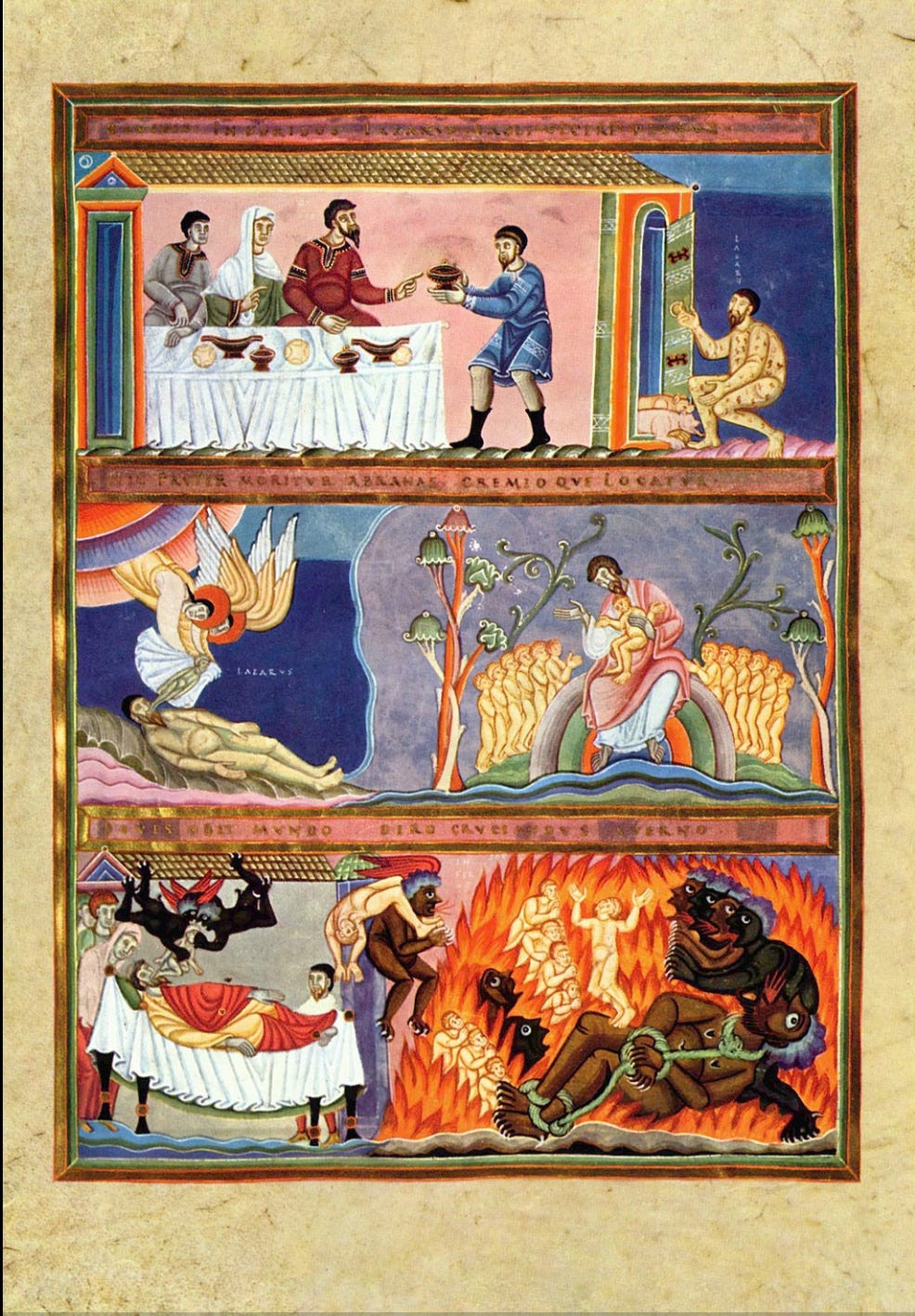

Lazarus and Abraham — Luke 16:19-31 (plus book announcement)

This week, I have been thinking a lot about the so-called catholic epistles,which comprise the letters of James, 1–2 Peter, 1–3 John, and Jude. They are called “catholic” because they are seen by scholars as having a generalized audience on the one hand (unlike the Pauline epistles that are addressed to communities) and they are non-Pauline, at least in a traditional understanding of what constitutes “Pauline”. So why do I say this if this article is about a parable in Luke? Well, to put it simply, it was a parable that kickstarted my interest in biblical scholarship, leading up to a project that will culminate in my first book. This publication will be a commentary on the letter of James, and shall be followed up with commentaries on the rest of the catholic epistles with a particular focus on their relationship to the rest of the Pauline school. Per the work I have been doing with The Voice of the Shepherd, the critical method will be centered on lexicography. I hope that these books will help the reader identify the oneness of the New Testament canon and how all of its components work together for a cohesive, redactional whole.

Taking this next step into publishing a full volume made me reflect on this journey with the text over the past five years. Almost two years ago, I wrote an extended tribute to Fr. Marc Boulos’s The Bible as Literature podcast, where I put to writing everything I had learned up to that point. It was a special occasion, being the 500th episode after nearly a full decade of programming. In short, The Bible as Literature changed my life, but I probably would not have come across it if it weren't for the Teach Me Thy Statutes podcast on the same Ephesus School Network. That podcast was hosted by my parish priest, Fr. Aaron Warwick, and he happened to launch the first episode around the time I was starting the process of joining the church. Not long after that, COVID-19 broke out across the United States, so there couldn't have been a more providential time to study scripture. After all, it was scripture that had been my main interest. Fr. Aaron laid the foundation for me to hear the text with fresh ears as an adult. In a world full of self-aggrandizing interpretations of the text, he would never exonerate our group from scripture’s admonition, but would invite his flock to submit to the uncomfortable tension of the Gospel. I had never heard a pastor preach so boldly in my life. My experience had typically been an “us versus them” orientation. A church I had been attending prior would routinely preach on the errors of outsiders, but never looked inward the way Paul invites us to in Romans 2. The assumption was that those of us who were “born again” already had our salvific moment. We were in the clear on judgment day, on that basis. I could never harmonize that opinion with the sense of urgency so evident in the New Testament. Not to mention, Matthew 25:31-46 tells us what judgment day is about, and it has nothing to do with “belief”. Fr. Aaron has always been committed to staying true to the Gospel, even when it makes us (i.e., Orthodox Christians) look bad. The impact his approach has had on me cannot be overstated, and I will always be grateful for his guidance in that regard.

Okay, okay, so when is this article going to discuss the parable as the title says? The connection between Fr. Aaron and the parable of the rich man and Lazarus has to do with it being, first of all, the subject of his MDiv thesis. Secondly, he summarized the thesis in an episode of the aforementioned podcast. His reading of the parable had Lazarus representing the outsider Gentile, and the rich man representing the Jewish elite. If one knows Luke’s Gospel well, this conflict between the proverbial rich and poor is not very surprising. But to my ears, it was striking and made me want to learn more. Even more impressive was the importance of Lazarus’s Hebrew name, meaning “God is my help” from eli (my god) ‘ezer (is help). Much of Fr. Aaron’s preaching and teaching was like this. It dealt directly with the text, and more importantly, with the language of the text. I had never heard preaching like this, with this kind of textual depth.

While many of his sermons and podcast episodes stuck with me, his reading of the rich man and Lazarus came to the fore when I was preparing a podcast episode of my own on the pericope of Eliezar of Damascus in Genesis 15. I instantly recognized that Eliezar and Lazarus were the same name. I also recognized that Abraham was a critical character in both stories, and both dealt with the inclusion of an outsider into the household of Abraham. I thought this was interesting, and it wasn’t far-fetched to assume that Luke had Genesis 15 in mind since 15–17 are so critical in Paul’s argumentation, especially in Romans and Galatians. In fact, the Rev. Dr. Bartosz Adamczewski, a Polish scholar of both testaments, reads the gospel of Luke as being built principally on Galatians, not only formally but sequentially as well. He links the rich man and Lazarus pericope (Luke 16:19-31) with Galatians 4:21-31, which is striking because Paul is retelling the story of Genesis 15–17, which I argue, is at the heart of the parable!

The section Lk 16:19–31, with its main themes of two different sons of Abraham, one not hearing the law and consequently perishing, the other one carried without any merits to the maternal womb, both being separated from each other, the law being ineffective as concerns salvation, salvation consisting in participating in the resurrection, and a negative judgment upon those related to the law, sequentially illustrates the main themes of the corresponding section Gal 4:21–31. The opening image of two differing men, who lived close to each other (Lk 16:19–21) and who were later identified as being in somewhat differing filial ← 177 | 178 → relationships to Abraham (Ἀβραάμ: Lk 16:22b.24–25.30), 203 illustrate the scriptural motif of Abraham having two sons (Gal 4:21–22). — Luke: A Hypertextual Commentary (p. 177)

In other words, it seems like both Paul and Luke are ultimately interested in this early section of Genesis, making it reasonable to at least argue that Eliezar of Damascus is related to the Lazarus of the Lukan parable.

Thus, I built my first academic presentation at the Orthodox Center for the Advancement of Biblical Studies symposium in August of 2022. I am linking a bulk of the paper I delivered, with only a few tweaks for presentation purposes. I still stand by this reading, and I think this connection powerfully connects Eliezar of Damascus, the unwanted inheritor of Abraham’s house, with the Lazarus who ends up resting in Abraham’s bosom.

I am immensely thankful for Fathers Aaron Warwick, Marc Boulos, Paul Tarazi, Timothy Lowe, Fred Shaheen, and Herman Acker for all of the work they do and for their encouragement of my work. Here’s to the next step, for the glory of the scriptural God!

The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus as a Retelling of Genesis 15–17 (Aug. 2022)

In the gospel of Luke, we have a unique parable about a rich man who ignores a poor man named Lazarus despite that said poor man being left at the gate of his household, relying on crumbs and covered in sores. There are several interesting details about this particular parable that make it stand out among the rest. The most obvious is that it is the only one in which characters are given clearly identifiable names and thus functions, corresponding to existing characters in the Old Testament. I am refraining from saying their names are proper nouns, since that concept is foreign to scripture. Every name has a meaning; every name is functional, and it just so happens that there are two identifiable Hebrew names here. The rich man is simply ὁ πλούσιος, but the characters of Lazarus and Abraham correspond directly to Old Testament characters.

Starting with Lazarus, it is important to note that this is a Hellenized rendering of the original Hebrew Eleazer. There are several characters in the scriptural corpus bearing this name. Probably the most famous occurrence is that of Aaron’s son in the book of Exodus. This name means “God helps”. There is a variant on this name with the possessive, which is Eliezer. In Hebrew, this would be rendered not as “God helps” but “MY God is help”. This variation is the one that occurs first in the canon. The original occurrence is in Genesis 15 with the character Eliezer of Damascus, and the next occurrence is in Exodus 18 with Moses’ second son. Eliezer of Damascus is of particular interest because this story also includes the character Abram, who is later renamed Abraham by the scriptural God in Genesis 17. Given the innate intentionality of names in scripture and the rare occurrence in Luke, the comparison of Genesis 15 and Luke 16 becomes incredibly interesting and may even suggest that the parable of the rich man and Lazarus is making a literary allusion to Abram and Eliezer of Damascus.

Genesis 15:1–6 ESV

After these things the word of the Lord came to Abram in a vision: “Fear not, Abram, I am your shield; your reward shall be very great.” 2 But Abram said, “O Lord God, what will you give me, for I continue childless, and the heir of my house is Eliezer of Damascus?” 3 And Abram said, “Behold, you have given me no offspring, and a member of my household will be my heir.” 4 And behold, the word of the Lord came to him: “This man shall not be your heir; your very own son shall be your heir.” 5 And he brought him outside and said, “Look toward heaven, and number the stars, if you are able to number them.” Then he said to him, “So shall your offspring be.” 6 And he believed the Lord, and he counted it to him as righteousness.

Luke 16:19–31 ESV

19 “There was a rich man who was clothed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day. 20 And at his gate was laid a poor man named Lazarus, covered with sores, 21 who desired to be fed with what fell from the rich man’s table. Moreover, even the dogs came and licked his sores. 22 The poor man died and was carried by the angels to Abraham’s side.[a] The rich man also died and was buried, 23 and in Hades, being in torment, he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham far off and Lazarus at his side. 24 And he called out, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus to dip the end of his finger in water and cool my tongue, for I am in anguish in this flame.’ 25 But Abraham said, ‘Child, remember that you in your lifetime received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner bad things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in anguish. 26 And besides all this, between us and you a great chasm has been fixed, in order that those who would pass from here to you may not be able, and none may cross from there to us.’ 27 And he said, ‘Then I beg you, father, to send him to my father’s house — 28 for I have five brothers — so that he may warn them, lest they also come into this place of torment.’ 29 But Abraham said, ‘They have Moses and the Prophets; let them hear them.’ 30 And he said, ‘No, father Abraham, but if someone goes to them from the dead, they will repent.’ 31 He said to him, ‘If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead.’”

Contra Jerusalem

Having heard both of these passages together, let’s first examine the parable of the rich man and Lazarus. There are many interpretations of this story, but the one that makes the most sense contextually is that the rich man represents the Jewish aristocracy and Lazarus represents those outside of that seemingly pious circle, be they gentiles or Jewish outcasts. Common arguments for this interpretation note the detail of the rich man being clothed in purple and fine linen, which brings to mind the ceremonial vestments for the Levites who have both kingship and priesthood. In other words, this rich man is representative of the religious leaders in scripture, who are consistently failing to properly shepherd the flock, as we hear time and time again in the prophetic writings. Lazarus, on the other hand, is representative of both the gentile community and those Jews who were considered outcasts by the Jerusalemite elite. His poverty refers to the lack of God’s Torah, which the Jerusalemite elite were rich in knowledge of. He is barred from receiving this bread in full, only receiving the crumbs, as he sits outside the gates. This is due to the gatekeeping of God’s instruction by the Jerusalemite elite, which, as context would suggest, is the main problem that the parable is speaking out against. This gatekeeping is of major concern to Paul, as is strongly evident from his epistles and especially Galatians, where it is the most clearly spelled out and explained. Thus, properly understanding this issue in the Pauline corpus is of critical importance towards approaching any New Testament text.

Luke’s Place in the Pauline School

Since most scholars are virtually unanimous that the Pauline letters predate those of the Gospel writings, there is no need to spend too much time on that point. What is less unanimous, but more relevant to this paper, is how the author of Luke-Acts incorporates the Pauline literature in these two narratives. The most striking feature of Luke’s corpus is that he alone actually composes a direct narrative of Paul’s life and ministry, mirroring that of his portrayal of Jesus’ life and ministry. None of the other Gospel writers mention Paul in their work directly, although several scholars have pointed out many instances where the evangelists have perhaps alluded to Paul in their writings. Nevertheless, the fact that the gospel accounts reflect the teachings of Paul’s epistles is self-evident, and the choice of Luke to continue the story of his Gospel narrative with that of Paul’s career should demonstrate an even more overt preoccupation with Paul and his conflict with the circumcision party. As the previous sentence would suggest, the precise role of the covenant of circumcision as it relates to the outsider was the main cause of this conflict. This is, again, most concisely expounded upon in Galatians, where Paul explains that it is obedience to God and his law that determines a child of Abraham and not circumcision of the flesh. This obedience to God is dubbed circumcision of the heart in the book of Deuteronomy, and then picked up in Jeremiah and Ezekiel, and finally by Paul. Therefore, Paul argues from scripture that neither circumcision nor uncircumcision is of any value if one’s heart is not circumcised. While Paul is drawing from Deuteronomy and the prophets for this understanding, the basis of his entire argument regarding the inclusion of the Gentiles goes back to the book of Genesis, specifically the content of chapters 15–17. Thus, it is readily apparent that Genesis 15–17 is essentially the source text of everything Pauline, and thus everything New Testament, so it is a big deal. What happens in these foundational chapters? The most notable, which are all featured prominently in Galatians and critical to its message, are as follows:

Abram’s faith counted as “righteousness”.

Promise of progeny for Abram.

Saga of Hagar and Ishmael.

Renaming of Abram and Sarai to Abraham and Sarah.

Imposition of the Covenant of Circumcision.

Announcement of Isaac’s birth.

Thus, the immediate takeaway from this section of Genesis is that:

Abram’s trust and obedience (faith) towards God’s instruction is what made him righteous, before both the covenant of circumcision and the Mosaic Law were introduced.

Abram’s progeny is to extend to a multitude of nations.

Hagar, an outsider, is mistreated by Sarai the Hebrew, and Ishmael is born according to the flesh (and not God’s promise).

Abram’s name is changed to Abraham, signifying the fatherhood of many nations (ie both Jew and Gentile).

The Covenant of Circumcision is enacted to display God’s complete control over progeny.

Isaac is born according to the promise, without Abraham’s involvement.

Even a cursory reading of Galatians would demonstrate that this is all essentially Pauline and at the forefront of his entire ministry as the apostle to the Gentiles.

Abram and Eliezer the Damascene

Moving back to the section in Genesis, the first important observation to make is that of the name Eliezer. It is peculiar that the author is even laboring to give this character a name, as merely stating that he was a foreign servant of Abram would have sufficed. The naming of Eliezer, thus, appears to be intentional. With Eliezer meaning my God is help it is rather odd to the ears to hear that Abram is outright rejecting God’s help. When we look at the context of the overall narrative of Genesis 15–17, this inclusion of Eliezer makes sense. Abram’s impatience and distrust in God’s promise to give him progeny are what propel him to first reject the outsider Eliezer and then to take matters into his own hands with the conception of Ishmael through Hagar. Abram wants his progeny. He wants his seed to continue, which is why he is uncomfortable with his outsider servant having a share in his inheritance. There is already a built-in tension with this in the text, however, because in chapter 17 Abram’s name is changed to Abraham because God is declaring that he will be a father of many nations. This opens up his progeny to a much larger volume than he anticipated, and would undoubtedly open up to the likes of Eliezer. This name-change occurs in conjunction with the covenant of circumcision, which, given this interpretation, can mean little else other than the mark of total submission to God, particularly with that of his function as patriarch. The cutting of the male sexual organ is the graphic image of this submission.

Abram as the Rich Man, Eliezer as Lazarus, and the Role of Abraham

If the naming of Eliezer in Genesis is peculiar, it is astronomically more peculiar that Lazarus is named in that parable. The parable could function perfectly well just to leave it as the poor man and the rich man. The text has a different agenda, it seems. Given the common interpretation presented previously, the parallel between these two passages is quite striking. For one, the rich man in the parable is functioning very much like Abram in the Genesis text. Both figures are rich and live lofty lives. The name Abram in Hebrew means Lofty Father and at several points in his life, as Abram, his wealth is consistently mentioned. Eliezer is similar to Lazarus, not merely in name but in their functions in the two respective stories. Eliezer in Genesis is awaiting Abraham’s inheritance, and Lazarus in Luke is awaiting the scraps from the rich man’s table. The rich man also treats Lazarus as if he were his servant when he demands that Abraham send him over to him to relieve his torment in Hades. It is also important to note that Lazarus is thrown or cast at the gate of the rich man. The Greek has ἐβέβλητο, which is from the verb βάλλω, meaning to throw. Here it is in the pluperfect passive, which, for my fellow grammatically challenged friends, basically means a completed action in the past happening to Lazarus, thus the translation that he had been cast there. This is significant because Lazarus is essentially dumped in the rich man’s domain, so the rich man has no excuse not to aid Lazarus. Lazarus is also seemingly forced to be there. Likewise, Eliezer of Damascus, being a servant, is forced into his role as Abram’s servant. This comparison makes sense with Abram’s narrative in the book of Genesis. That story is painstakingly played out in Abram’s struggle with the outsider and progeny throughout Gen. 15–17, including the story of Hagar and his son Ishmael.

The inclusion of Abraham in the story is interesting, especially if we equate Abram with the rich man. This is where the functionality of the names becomes incredibly important. Father Paul Nadim Tarazi has famously emphasized the importance of the Hebrew names throughout his career. In essence, they control the function of the characters in the story. Because Abram and Abraham have different names, they are, in essence, different characters. This is not too foreign to modern popular culture. In the Star Wars franchise, Jedi Anakin Skywalker falls to the dark side and is renamed Darth Vader by his Sith master. Even though Anakin and Vader are the same in the sense that one becomes the other, they are not used interchangeably. When the character is functioning as a Jedi, he is Anakin. When he is functioning as a Sith, he is Vader. His persona changes, and thus his character changes, and like scripture, it is so when the name changes. So, what does Abraham’s name mean? This is a complicated question with many potential answers, but it is made up of the Hebrew word ab (father) and the Semitic root r-h-m,which can have a host of meanings. He is renamed Abraham because he will become the father of many nations, which implies inclusivity. Interestingly, raham is also phonetically similar to reḥem (womb), which fits nicely with the language of Lazarus being in Abraham’s bosom in Luke’s parable. So Abraham represents the inclusion of the multitude of nations sharing table fellowship under the law of the scriptural God. Lazarus partakes in the rich man Abram’s inheritance and his household, comforted in Abraham’s bosom of mercy.

Luke’s Reasons for Constructing this Parable

If the parable of the rich man and Lazarus is indeed an allusion to the story in Genesis 15, that leaves the rich man to be an, albeit subtle, allusion to the character of Abram himself. It is a dig against the hearer. It is also a clever way to use a story from the Hebrew Bible in a new way to make the original story even more relevant. The parable of the rich man and Lazarus could thus be seen as a sequel to that of Eliezer and Abram. It could also be framed as a fulfillment of Genesis 15. Likewise, the parable also hones in on Paul’s allegiance to the εὐαγγέλιον τοῦ Χριστοῦ over and above all traditions of men, including and especially the traditions of their forefathers. Abram represents this as the exalted father. To put the rich man in the story as a deliberate call back to Abram is a lucid way to belittle the Judean obsession with Abraham as their forefather. This also uppercuts the tendency of the Judeans, and many Christians and Jews today, to make Abram the hero of the story. And finally, the crimson thread of all of this is the inclusion of the outsider. The refusal to do this is to refuse the gospel teaching and thus be workers against Christ. The gospel breaks boundaries, whether they be ethnic, cultural, creedal, or religious.