Striving After Wind ( רַעְיוֺן רוּחַ) — Ecclesiastes, Daniel, and an Excursus on Avestan Literature

In Daniel 2:29, the prophet addresses King Nebuchadnezzar before revealing to him the interpretation (פִּשְׁרָא pišrā cognate with تَفْسِيرً tafsir in Arabic through the root fsr) of his dream. Daniel, under the name Belteshazzar, addresses the King’s “thoughts” — רַעְיוֺן ra‘yōn in Aramaic.

אַנְתָּה מַלְכָּ֗א רַעְיֹונָךְ֙ עַל־מִשְׁכְּבָ֣ךְ סְלִ֔קוּ מָ֛ה דִּ֥י לֶהֱוֵ֖א אַחֲרֵ֣י דְנָ֑ה וְגָלֵ֧א רָזַיָּ֛א הֹודְעָ֖ךְ מָה־דִ֥י לֶהֱוֵֽא׃

As for you, o King, upon your bed your thoughts (רַעְיֹונָךְ֙) came up concerning what would happen after these times. And the revealer of mysteries shall make known to you what shall happen. — Dan. 2:19

This is interesting because it is functionally linked with the vanity of the oikonomia of the city-state. This is powerfully illustrated in the book of Ecclesiastes, where the author (purporting to be the king of Israel) writes ad nauseam about that very topic.

On the enterprise of Greek philosophy, he writes:

וָאֶתְּנָ֤ה לִבִּי֙ לָדַ֣עַת חָכְמָ֔ה וְדַ֥עַת הֹולֵלֹ֖ות וְשִׂכְל֑וּת יָדַ֕עְתִּי שֶׁגַּם־זֶ֥ה ה֖וּא רַעְיֹ֥ון רֽוּחַ׃

And I gave my heart to know wisdom, and to know madness and folly. I perceived that this also was striving (רַעְיֹ֥ון) after wind. — Eccl. 1:17

On the labors and activities of man:

כִּ֧י מֶֽה־הֹוֶ֤ה לָֽאָדָם֙ בְּכָל־עֲמָלֹ֔ו וּבְרַעְיֹ֖ון לִבֹּ֑ו שֶׁה֥וּא עָמֵ֖ל תַּ֥חַת הַשָּֽׁמֶשׁ׃ כִּ֧י כָל־יָמָ֣יו מַכְאֹבִ֗ים וָכַ֙עַס֙ עִנְיָנֹ֔ו גַּם־בַּלַּ֖יְלָה לֹא־שָׁכַ֣ב לִבֹּ֑ו גַּם־זֶ֖ה הֶ֥בֶל הֽוּא

For what shall there be for man in all his toil and in the striving (רַעְיֹ֖ון) of his heart with which he toils under the sun? For all his days are sorrowful and burdensome. Even at night his heart takes no rest. This too is vanity. — Eccl. 2:22–23

And about the vanity of the monarchy:

טֹ֛וב יֶ֥לֶד מִסְכֵּ֖ן וְחָכָ֑ם מִמֶּ֤לֶךְ זָקֵן֙ וּכְסִ֔יל אֲשֶׁ֛ר לֹא־יָדַ֥ע לְהִזָּהֵ֖ר עֹֽוד כִּֽי־מִבֵּ֥ית הָסוּרִ֖ים יָצָ֣א לִמְלֹ֑ךְ כִּ֛י גַּ֥ם בְּמַלְכוּתֹ֖ו נֹולַ֥ד רָֽשׁ׃ רָאִ֙יתִי֙ אֶת־כָּל־הַ֣חַיִּ֔ים הַֽמְהַלְּכִ֖ים תַּ֣חַת הַשָּׁ֑מֶשׁ עִ֚ם הַיֶּ֣לֶד הַשֵּׁנִ֔י אֲשֶׁ֥ר יַעֲמֹ֖ד תַּחְתָּֽיו אֵֽין־קֵ֣ץ לְכָל־הָעָ֗ם לְכֹ֤ל אֲשֶׁר־הָיָה֙ לִפְנֵיהֶ֔ם גַּ֥ם הָאַחֲרֹונִ֖ים לֹ֣א יִשְׂמְחוּ־בֹ֑ו כִּֽי־גַם־זֶ֥ה הֶ֖בֶל וְרַעְיֹ֥ון רֽוּח

Better was a poor and wise youth than an old and foolish king who no longer knew how to take advice. For he went from the house of chains to the throne, though in his own kingdom he had been born poor. I saw all the living who move about under the sun, along with that youth who was to stand in the king’s place. There was no end of all the people, all of whom he led. Yet those who come later will not rejoice in him. Surely this also is vanity (הֶ֖בֶל hebel) and a striving (רַעְיֹ֥ון) after wind. — Eccl. 4:13–16

Through the itinerary of this world, Nebuchadnezzar’s thoughts reflect the same futility of the laments of Ecclesiastes. The kingdom that he built with his own hands, according to his striving (רַעְיֹ֥ון), will all come to naught at the arrival of the Persian Cyrus from the Achaemenid dynasty. Nebuchadnezzar’s purposes, embodied in the function of רַעְיֹ֥ון, will be canceled out for the sake of God’s purposes. How does God do this? He makes Cyrus his shepherd.

Why is this striking? It’s from the same triliteral root: ר-ע-ה (resh-ayin-hē).

This root is functionally tied to the type of leadership employed by a Bedouin shepherd. The first occurrence is, interestingly enough, linked with Abel (הֶ֖בֶל hebel), the same word used in Ecclesiastes to denote “vanity”.

וַתֹּ֣סֶף לָלֶ֔דֶת אֶת־אָחִ֖יו אֶת־הָ֑בֶל וַֽיְהִי־הֶ֨בֶל֙ רֹ֣עֵה צֹ֔אן וְקַ֕יִן הָיָ֖ה עֹבֵ֥ד אֲדָמָֽה׃

And again she gave birth to his brother Hebel, and Hebel was a pastor (רֹ֣עֵה) of the flock and Qayin was a worker of the ground. — Gen. 4:2

Here, both of these words are used in proximity just as they are in Ecclesiastes. The text of Genesis clearly prefers Abel to his brother Cain, but in doing so, it still gives the label of “vanity” to its preferred character. This is striking. It’s not that the Bedouin is not vain (as in passing away), it’s that the Bedouin understands that he will pass away, and submits to this reality rather than trying to fight it. It is an act of īslām in the functional sense. This is the conclusion that Qohelet, the “king” of Jerusalem, comes to understand in his book. All of his works are vanity, and all that remains is the Lord’s instruction. The king of Jerusalem becomes a functional shepherd. This is the way God uses Cyrus. When men strive, it’s vanity. When God strives, it’s pastoral and leads to the oasis of living water.

Excursus on Avestan Parallels

As part of my ongoing studies of the book of Daniel, I have been teasing the interaction between the Torah and the wisdom traditions of the Ancient Near East. While I usually speak about the Greek wisdom tradition spread by the exploits of Alexander, the Persian religious/wisdom traditions have their own fascinating history. The sources are much more sparse and reliant on a considerable amount of guesswork, but there are some interesting parallels that are worth considering.

First of all, the Persians had a reputation among the Greeks for being lazy, rich, effeminate, and mentally aloof. The historian Samuel K. Eddy outlines this reputation in his magisterial work The King is Dead: Studies in Near Eastern Resistance to Hellenism 334–31 BC (1961), where he writes:

Herakleides of Pontos in Asia Minor accused the Persians of being more devoted to luxury and pleasure than any other people; another Herakleides, he of Kumai, thought the royal court spent its nights trifling with women — Artaxerxes III of all persons being said to have three hundred harp-playing concubines. Much the same tale came from Klearchos of Kypriote Soloi. While such gossip was pure propaganda put out by seemingly knowledgeable eastern Greeks to win sympathy for a war of liberation, the picture came nonetheless to be believed, and even a man like Aristotle thought of Asiatics as the pawns of dissipated despots, and all Asia a community of male and female slaves. Wherefore, he added, the poets sing, “It is meet for Hellenes to rule over barbarians.” In Greek eyes, then, the Persian Empire was a place of fabled wealth, of gold, silver, splendid horses, of amazing agricultural fertility, all possessed by weaklings. (p 6)

The Bible itself seems to incorporate this stereotype, although it does so also at the expense of its own kings, such as Solomon, and the kings of Babylon, such as Nebuchadnezzar and Belshazzar. The same kind of debauchery goes all around, although it is notably Cyrus and Darius who are upheld as God’s instruments and generally seen as being stable leaders. This is patently not the case with Ahasuerus (possibly Xerxes) in the book of Esther. There, he is certainly aloof mentally, partying and drunk all the time, as well as impulsive. What’s interesting is that, besides this fact, God’s providence works silently in the background. It doesn’t matter that Ahasuerus is a dunce. God still saves Esther, Mordecai, and the rest of the Judeans in Susa regardless. Whether the king is stable (like Cyrus) or unstable (like Ahasuerus), God will complete his purpose.

In presenting kings in this manner, the Bible is not picking on the Persians or the Babylonians in particular. We see the kings of Israel and Judah act the same way. We see the Pharaohs of Egypt act the same way. There’s no room for Hellenistic arrogance in the Bible. The guidance isn’t found in the monarchs (including Platonic philosopher kings) that are passing away (ie, are vanity), it is in the providence of the scriptural God, who only sees “kings” as princes and only deals with them as temporary pastors!

There is an interesting literary parallel produced by the priestly class of the Persians following their subjugation by the Hellenists. In fact, in Zoroastrian tradition, Alexander is dubbed “the accursed” (𐭬𐭩𐭰𐭲𐭠𐭢 gizistag). The reason why this is interesting to me is that they likely would have been acquainted with the priestly class in Babylon, which, according to the Tarazian thesis in The Rise of Scripture, was behind the composition of the Hebrew Bible. The distance from the Persian intellectual capital (Susa) and that of Babylon would have been about 10–15 days, given that they were about 225 miles apart. It is certainly possible, not to mention there being a considerable number of Persian nobles, priests, and scribes who remained in Babylon following the siege. It is almost certain that they interacted with each other, and according to Eddy, both the Babylonians and the Persians wrote extensively against the imposition of the Hellenists!

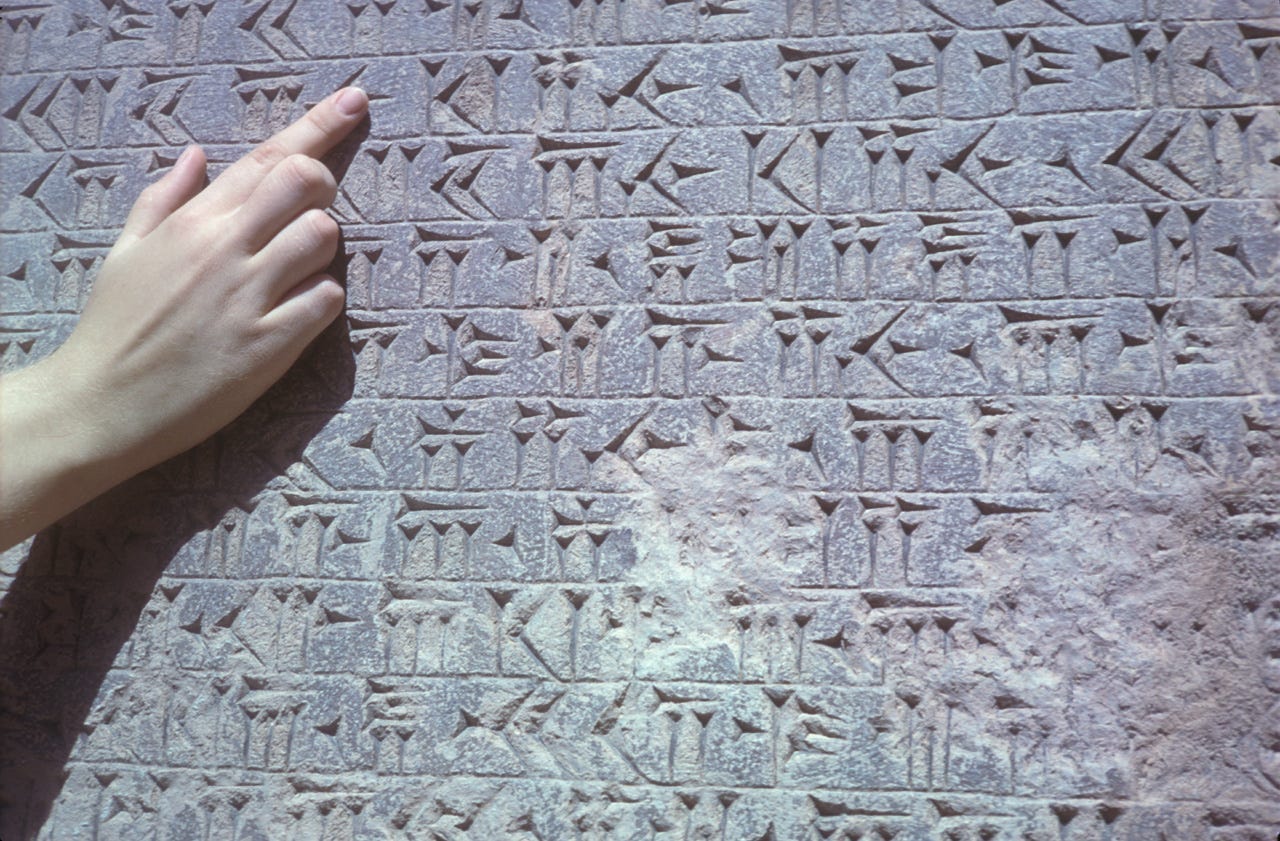

So what about practical examples from this Persian literature? To begin this discussion, we must start with their main literary personality — Zarathustra. His name is fascinating and gives us a clue as to his function. It is a combination of the words 𐬰𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬚 zarath — driver/herd and 𐬎𐬱𐬙𐬭𐬀 uštra — camel (cognate with Sanskrit उष्ट्र ustra of the same function), so the rendering of the full name 𐬰𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬚𐬎𐬱𐬙𐬭𐬀 would be camel-driver or he who herds camels. Like many of the biblical names, Zarathustra is first and foremost a pastoral figure. This is striking because, like Babylon, the Achaemenid Empire was structured with the king at the top who embodied Ahura Mazda (the wise ashura/ god/ lord), with priests and scribes under him. The Behistun inscription tells of Darius’s military success against a potential usurper to his throne, which the king links with the favor of Ahura Mazda. This is typical in Ancient Near Eastern reliefs. The King’s deity usually gets the credit for his exploits.

While Ahura Mazda is mentioned by name, there is nothing said about the Avestan character Zarathustra. This doesn’t necessarily mean that such a character didn’t exist yet in the tradition, but it does possibly indicate that the authors of the Avesta (sacred scripture of the Zoroastrians) may have crafted Zarathustra as a nomadic foil to the failed monarchy of the Achaemenids. In other words, instead of making the central figure in the Gathas (liturgical songs in the Avestan canon, similar to the Psalter) one of the Persian kings, the authors introduced a pastoral figure who was a remembrance of a nomadic Central Asian past before the advent of the monarchy. It is worth noting that the Avestan word 𐬰𐬀𐬭𐬀 zara, likely related to 𐬰𐬀𐬭𐬀𐬚 zarath, connotes “antiquity” — giving the name even more weight.

The Zarathustra of the Gathas functions very much like David in the Psalms, who, even though he is a “king” (in the case of David), is parallel to the eschatological David of Ezekiel, who actually functions as a prince and a shepherd/ pastor.

וַהֲקִמֹתִ֨י עֲלֵיהֶ֜ם רֹעֶ֤ה אֶחָד֙ וְרָעָ֣ה אֶתְהֶ֔ן אֵ֖ת עַבְדִּ֣י דָוִ֑יד ה֚וּא יִרְעֶ֣ה אֹתָ֔ם וְהֽוּא־יִהְיֶ֥ה לָהֶ֖ן לְרֹעֶֽה וַאֲנִ֣י יְהוָ֗ה אֶהְיֶ֤ה לָהֶם֙ לֵֽאלֹהִ֔ים וְעַבְדִּ֥י דָוִ֖ד נָשִׂ֣יא בְתֹוכָ֑ם אֲנִ֥י יְהוָ֖ה דִּבַּֽרְתִּי

And I will make stand over them one pastor, my slave David, and he shall pasture them. He shall pasture them, and he shall be a pastor to them. And I, Yahweh, will be God to them and my slave David a prince among them. I, Yahweh, have spoken. — Ezek. 34:23–24

The pastoral nature of Zarathustra is firmly established in Yasna 29, a famous section of the Avestan canon which features a parable concerning a sacrificial cow who bears the world’s iniquity. This is colloquially known as “The Cow’s Lament”.

Since I am not sufficiently educated on the subject, I will rest the interpretation of the passage to the analysis of Scott L. Harvey, Winfred P. Lehmann, and Jonathan Slocum whose work on Yasna 29 can be located here: https://lrc.la.utexas.edu/eieol/aveol/10.

These are their comments:

The cow represents humanity at large, the Wise Lord’s great flock of men. Her plight is their plight and the provider she seeks is the virtuous man who can lead them to prosperity. Zarathustra opens the hymn with the cow plaintively asking her Fashioner why He created for her such a sorrowful existence and imploring him to wrest her from its estate. In verse two, the Fashioner asks Truth to respond to the cow. Verse three is not easily attributed, though one may presume it is Truth’s reply. Zarathustra makes the verse serve double duty, both as a warning against questioning the intentions of the gods and implying that Truth has sent him — the poet — as the ‘savior’ who is sought by the cow: “he to whom I shall go … will be the strongest of beings.” This introduces a major theme of the hymn. Verses four and five then read as the first direct address to Ahura Mazda, his Wise Lord. Yasna 29 continues with Ahura Mazda’s response to Zarathustra’s invocation. He appears to ignore Zarathustra himself and address only the cow, whose inquiry began the hymn. Zarathustra, as poet, seems to be using this speech to begin a progression to his main point, i.e. that it is he who is the spokesman who can lead humanity to their god. In verse six, Ahura Mazda declares that there is no one righteous enough to play this role, but then asks, in seven, if this is really so. In verse eight, Good Mind personified determines it is not, for Zarathustra Spitama stands ready to sing the Truth, inspired by the sweetness of right thinking. Verses nine through eleven then show the cow’s reluctance to accept Zarathustra, Zarathustra’s willingness to accept the responsibility, and finally the cow’s acceptance of Zarathustra as her ambassador to the gods and Mazda’s ambassador to the world. —Lessons 1&2

The parallels to biblical literature is striking here. The obvious link is with the imagery of the suffering servant, but also the establishment of a righteous pastoral figure who leads humanity out of bondage through the wisdom of the deity. Zarathustra isn’t a king, and there’s no mention of a temple or any city. It is all pastoral.

There is considerable debate about how to date some of this literature. The lack of primary sources makes it considerably difficult to figure out a timeline. The aforementioned scholar, Samuel K. Eddy makes a compelling case for composition during the Hellenistic period (see page 18 of his book), especially when it concerns the Bahman Yasht, a piece of literature that straight up parallels Nebuchadnezzar’s dream in the book of Daniel.

Here is Eddy’s take on the similarity:

Again, these are interesting parallels. Many scholars have speculated that Zoroastrianism influenced the Abrahamic religions. Perhaps there actually is something to that, only, my offer is to say that both the Hebrew and Avestan canons were composed in proximity by priestly and scribal acquaintances who were both writing against the influence of Hellenism and Alexander the Macedonian.

As a final thought, I’d like to shout out Matthew Cooper for his cutting scholarship, which has inspired me to broaden my horizons while still staying focused on the mission at hand. His thesis about the closeness of Western and Eastern Asia, with Central Asia caught in the crossfire, is exciting to behold as it blossoms. There’s something to the closeness of these traditions that has never been explored in this way before. It is the rejection of Hellenism and Alexander, and the embrace of functionality and the pastoral open-air wilderness.