My most formative year was 2012. I was thirteen years old and in Middle School. It was also an election year, and the first one that I paid attention to. For the first time, I was having political discussions, investing time in understanding positions people held, and learning how to balance intuition, knowledge, and reason to form my own opinions. Middle School provided a critical atmosphere for this exploration, because it was the first time that I was exposed to people of different backgrounds. At this age, most of us still saw the world through the eyes of our parents. I was brought up by a single mom who was relatively liberal but never held zealous opinions one way or another. I remember asking her about a lesbian couple I saw on TV, and her response was “well, some people do things that are different. We have to respect them, though”. So from there, someone “being gay” wasn’t a big deal to me. It was natural part of living in an eclectic world. People are different, and that’s okay. It made perfect sense to my little kid mind. I still thank my mom for that wisdom. But then, I started having friends whose parents were considerably more conservative — some very much so. I remember one of my best friends had parents who were extremely invested in the Tea Party Movement, which sprung up in the wake of the Obama administration, especially after the signing of the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare). They were certain that this crossed an important line, and that Barack Obama was a Marxist who was trying to destroy the country.

I do admit, such strong opinions blew my mind at the time. Was there something my relatively apolitical family was missing? Sometimes I feel like part of my interest in politics (and religion) had to do with understanding why these systems and ideologies compel people to act the way that they do. Speaking of religion, this friend was raised in a highly charismatic denomination (Assemblies of God) which blended contemporary Evangelicalism with elements from the Pentecostal movement. The opposition towards the Obama administration, and the “Left” in general wasn’t just a difference in political outlook — it was a full blown spiritual war. That’s why it was shocking to me when this friend and I would talk about God and the Bible, a subject I had been interested in since I was a kid. I wasn’t raised in a particular denomination, but my father’s side was Roman Catholic and my mother’s side was non-denominational Protestant (or Baptist-lite as I like to say). Even then, my mom and I hardly went to church. Sometimes we would go with certain family members, or on holidays. But usually, my church attendance occurred when my paternal grandmother took me to Mass. I loved the aesthetic of the Catholic Church, even if some of the formality was foreign to my 21st century suburban sensibilities. Catholic Mass really felt like church. Growing up, I didn’t even realize there was much of a difference, other than Catholicism being more rigid and traditional, whereas the churches my mom would take me to were contemporary and laid back. Despite my mom not taking me to church directly, she sent me to a religious elementary school and to church camp during the summers. It was in these environments that I was first exposed to the Bible, albeit in a very mild mannered way. While the school was associated with the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), the administration and student body came from all different confessional backgrounds. So there wasn’t an emphasis on any sort of doctrinal orthodoxy — other than the emphasis on non-violence and silent worship. We didn’t learn anything about the Trinity, penal substitutionary atonement, or the differences between Catholics and Protestants (I don’t remember even hearing the word “Protestant” until I read an American history textbook in Middle School). Rather, we learned about God’s love for his creation, and the importance of acting peaceably with people. There were three paintings I saw all the time that illustrated these two points. They had a tremendous impact on me.

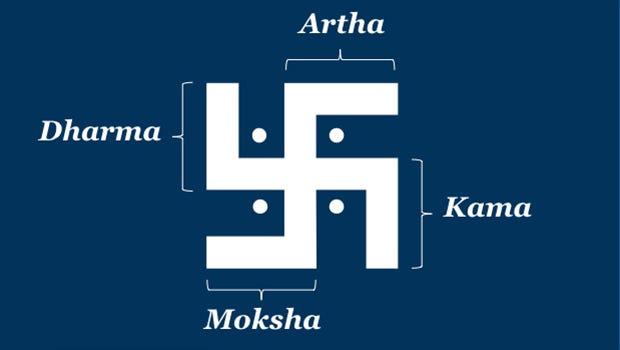

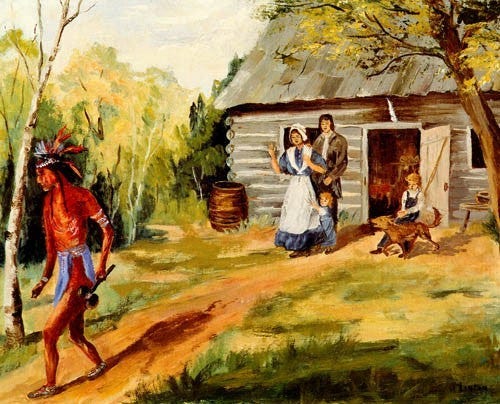

Two of them centered around the story of Native Americans entering into a Quaker Meeting with weapons drawn. They were hired by the British Army in 1777 to attack settlements in New York. The Quakers were the only group who didn’t hide. They simply went on with life as normal, and met for worship despite the danger. When the Native warriors arrived to the meeting house, one of the parishioners who knew the language invited them to worship with them. Touched by this, the war party put down their weapons, joined them for worship, and then placed a white feather above the door signaling to others that the house was to be unharmed.

The third painting depicted a typical Quaker meeting in England, with Christ in the midst of worship. It was taken from Matthew 18:20,

“Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there I am in the midst of them.”

It always comforted me considerably, and I think about it whenever I go to Divine Liturgy.

I bring this up, because my impression of the Bible’s teachings were characterized by the Beatitudes. To me, that was the quintessential message of scripture. Love your neighbor. Turn the other cheek. Forgive. I truly had no idea how a message of such simplicity could be so ideologically divisive among people who claimed to uphold it. Even when I went to the church summer camps, which were far more Evangelical in their orientation, my mind had already been molded by the Quaker emphasis on praxis. So it was shocking when my friend (through the influence of his family) would tell me that Catholicism was unbiblical, homosexuality was an abomination, and that correct belief was far more important than correct action. This was the first time I had ever heard that good people could go to Hell, and bad people could go to Heaven just on the basis of what they believed. And he had the Biblical receipts to prove it. I was honestly crushed. Christianity wasn’t about forgiveness of sins and loving your neighbor. It was about dogma, and upholding orthodoxy, even at the expense of people. It was important to impose “Biblical Christianity” onto others because it was the truth! I turned to the internet to make sure I wasn’t going crazy. All of the Christians I watched on Youtube sounded just like my friend. Maybe the Bible was a scam, and church was just a means to control people. By the behavior of the Christians I perceived, that seemed like the rational answer. For the first time in my life, I didn't believe in God. It was all a ruse. It was like finding out Santa wasn't real, but way, way worse. It was existential.

Around that time, I had also taken a liking to history. All of these experiences made me deeply interested in people, and how those people behave. A ton of history centers around how religion compelled their behavior. The results were always mixed. Religious beliefs that inspired Catholic monks to build schools and hospitals, were the same beliefs that inspired them to burn heretics and impose the inquisition. What did “Christianity” actually mean in that context? I noticed a similar tension with Islam, which I first learned about my freshmen year of High School in a Human Geography class. The same religion that inspired advances in science, mathematics, jurisprudence, social quality, and women’s rights was also the same religion that inspired Al-Qaeda to fly commercial jets into the Twin Towers and behead infidels in Syria. What did the cross represent? What did the star and crescent represent? It was different depending on who you asked. I had met atheists who were dismissive of religion as a whole. I never felt that way. I always wanted to believe something. I had a desire for God. But all of them felt like ideological projections, without much substance.

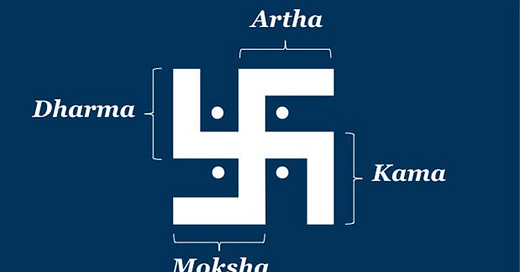

It came together for me when I started learning about Eastern religions like Buddhism and Hinduism. It was then that I learned that the “Swastika”, made infamous by Nazi Germany, was originally a symbol of blessing in the Indian subcontinent. Function mattered more than the symbol, but symbols are easily exploited. Imagery is powerful for the human being. It is an evolutionary mechanism, seared into our psychological operations. But at the end of the day, imagery is never truly universal. The devil is in the details.

That’s the problem with Platonism and how it has affected our world. I’ll never forget an “honors world history” class where the teacher initiated the course, not with a discussion of an event, but with Plato’s Gorgias dialogue. It seemed like a confusing way to start. It was a history class after all, not a philosophy one. But therein was the problem with my presupposition. History is molded by philosophy! It took me a long time to understand the lesson my history teacher was offering. Whether we like it or not, we are as much a product of men’s thoughts as much as we are their actions.

It dawned on me much later that the tension I had experienced with religion as a kid centered around two approaches to the faith. The Quaker approach was functionalist. The story compels us to live a certain way — namely to serve our neighbor. The Evangelical approach was Platonic. There’s dogma to uphold, and orthodox belief concerning the text is the key to salvation. The orthodox critique of the Quakers would be that they diminish Christianity by de-emphasizing the beliefs that make it unique. “If the Bible is just about honoring God by serving your neighbor, you don’t need religion for that.” And they’re right, you don’t. But therein lies the rub. The God of the Bible doesn’t need YOUR religion. He needs you to show mercy to His children (Matt. 7:22–24, 25:31–46). That’s the tension I was experiencing. I read Matthew and Genesis the most when I was growing up. Words like these from Jesus ran through my mind all the time.

In the political sphere, I heard many on the “religious right” appeal to the importance of the preservation of the “Judeo-Christian” values of the West. Western civilization was under attack, and it needed to be preserved. This civilization was, of course, the pinnacle. When I learned about Hegel, I understood where this obsession with “the ultimate society” came from.

Every society thinks it’s eternal. The Romans, in their heyday, would be distraught to know that their civilization was overrun by Germans from the north and Arabs from the south. A generation comes, a generation goes. Nothing built with stone lasts forever.

That’s where this sudden appeal to religion by atheists like Richard Dawkins, Jordan Peterson, and Ayaan Hirsi Ali is so nefarious. They aren’t interested in the Bible. They are interested in the West. If the religion that held Western civilization together was Norse Paganism, they’d be on board with that too. I’m sure of it. They like the fact that the western Christian institutions offer a buffer against Islam. It is a hatred of Islam. That’s why they dislike Quakers. Quakers are true Muslims. The administrators and students at the Friends School in Ramallah, Palestine understand that. They are living it.

The Platonist West represents insecurity. They are modern day examples of Julian the Apostate, who briefly returned Roman paganism as the state religion in 361. He viewed Christianity as a foreign virus that threatened to destroy Roman culture. Modern day conservatives (and liberals) would be on his side.

The Jubilee video of Jordan Peterson debating “20 atheists” really made something clear to me — he’s Socrates. He’s Plato’s ideal character who presents himself as “knowing nothing”, and using that as a mechanism for deconstructing the opposition. Once the opposition is deconstructed, Plato’s philosophy can be presented. That’s what Jordan Peterson does when he constantly redefines and recontextualizes words where they are functionally meaningless. It’s a gaslighting technique. Socrates was a gaslighter. That’s why Plato used him as a character. Unlike his student Aristotle, he didn’t just outline his philosophy in a series of treatises. He outlined it slowly through the pedagogical dialogues where Socrates dismantles the sophists of his day. He’s the guy who always questions you, not to refine your thinking, but to tear you down. It’s destructive. Plato wanted to replace Athenian democracy with the Philosopher King who ruled by his system. A huge part of making Plato’s Politeia work centers on gaslighting the population. Don’t believe me? Look up the Noble Lie! For Peterson, and many of his ilk, religion represents the Noble Lie. They like that they can use it as a mechanism of control. They want to control the population. That’s why he’s obsessed with gender ideology, even more so than LGBT folks. He sees Western hegemony crumble, and he can’t let the course of history have its day. The West is sacred.

In dealing with a topic I’ve touched on before, it’s powerful how Paul engages with these mechanisms of control. He takes hold of the loaded word λόγος and makes it synonymous with his Gospel. At the same time, in his letter to the Romans, he dismantles Roman and Jewish law (lex, cognate with λόγος) by taking ultimate control away from the governing authorities (Caesar and the Sanhedrin) and giving it to God the Paterfamilias through the representation of his crucified barbarian son! In his first letter to the Corinthians, he dismantles the Greek philosophical λόγος and replaces it with the λόγος of the cross! (1 Cor. 1:18)

It’s the WORD of the cross, NOT the SYMBOL of the cross. Symbols can be controlled and warped. That’s why Plato loved them. Words are written and relentlessly copied and memorized. They are, by definition, out of your control once they have been written. Why do we put contracts into writing? The written word keeps us accountable. Destroy all the Qur’ans in the world, and the text will still exist with the thousands living who have the whole thing memorized!

This is why the life’s work of the Very Rev. Dr. Paul Nadim Tarazi is so important. His demonstration in The Rise of Scripture (OCABS, 2017) that the Bible is a 3rd century BCE literary product combatting and dismantling Hellenism is so powerful. His book not only reminded me of, but reacquainted me with those critical intuitions I had as a child — only this time I could reflect on the subject as an adult. Paul was right in 1 Corinthians 13. Things become clearer as you get older.

Those who seek to abuse scripture by using it to control others for their benefit, are doing so under its condemnation. They ought to stop philosophizing and start reading Romans 15. There’s a reason why street preachers only select verses from Romans 1–10. The sacred “Roman’s Road” completely disregards the last five chapters!

So let’s live in reality, as the Bible calls us to do. In lieu of online debates, help someone out today. Serve your community. Learn a language. Take up lexicography. Read. Educate yourself. Protest. Do something.

Right, Blaise! Genuine symbols arise from the mysterium tremendum et fascinans and as such have a life of their own; however, they can be subverted to serve demonic purposes as your fine article suggests and history bears out. Also, I am forever correcting my students' essays that assert this or that statement in the Hebrew Bible is "symbolic," wherein their desire is to blunt the force of hearing its (Hebrew) words. I constantly try redirecting them to the letter of the text, but as I get older I just want to buy a rubber stamp with a single word, like BULLSH*T. Great article.

דבר מצלב