The cross (σταυρός) was the critical piece for the Pauline school. This is curious because unlike most of their vocabulary, σταυρός does not appear in the Septuagint. Likewise, there isn’t a direct connection with the Hebrew. And yet, σταυρός is the key for Paul when preaching the εὐαγγέλιον. Why is this so? To understand this, we must first follow his argument to its source. For Paul, the power of the σταυρός is its public exhibition.

Ὦ ἀνόητοι Γαλάται, τίς ὑμᾶς ἐβάσκανεν, οἷς κατ’ ὀφθαλμοὺς Ἰησοῦς Χριστὸς προεγράφη ἐσταυρωμένος;

O foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you? It was before your eyes that Jesus Christ was publicly portrayed as crucified. — Gal. 3:1

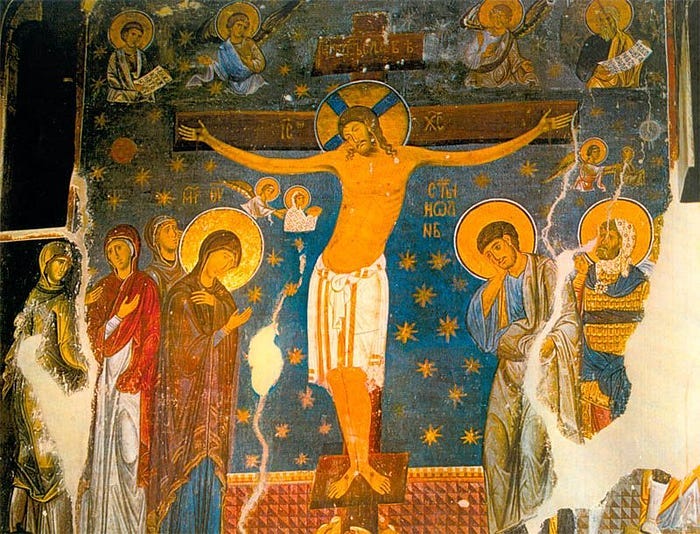

The key phrase here is οἷς κατ’ ὀφθαλμοὺς (before your eyes) and προεγράφη ἐσταυρωμένος (presented crucified). Accurately rendering προεγράφη is difficult because it literally means “to write beforehand” and is used that way by Paul in Romans 15:4 and Ephesians 3:3, as well as in Jude 1:4. However, it does have a secondary value as “to present openly, placard, or advertise”. This is because of the flexibility of the Greek verb γράφω which can refer to writing words but also to painting, hence in Byzantine (Greek) Christianity, we hear of icons being written rather than being painted. So for Paul, σταυρός is a visual phenomenon and the image of the cross that was presented to the Galatians should have been enough to deter them from rejecting the gospel.

Why is the visual aspect of σταυρός so paramount? Later in this chapter of Galatians, Paul infers Deuteronomy to communicate his point.

Χριστὸς ἡμᾶς ἐξηγόρασεν ἐκ τῆς κατάρας τοῦ νόμου γενόμενος ὑπὲρ ἡμῶν κατάρα, ὅτι γέγραπται Ἐπικατάρατος πᾶς ὁ κρεμάμενος ἐπὶ ξύλου

Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us — for it is written, “Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree” — Gal. 3:13

In Deuteronomy we hear,

וְכִֽי־יִהְיֶ֣ה בְאִ֗ישׁ חֵ֛טְא מִשְׁפַּט־מָ֖וֶת וְהוּמָ֑ת וְתָלִ֥יתָ אֹתֹ֖ו עַל־עֵֽץ לֹא־תָלִ֨ין נִבְלָתֹ֜ו עַל־הָעֵ֗ץ כִּֽי־קָבֹ֤ור תִּקְבְּרֶ֙נּוּ֙ בַּיֹּ֣ום הַה֔וּא כִּֽי־קִלְלַ֥ת אֱלֹהִ֖ים תָּל֑וּי

And if a man has committed a crime punishable by death and he is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, his body shall not remain all night on the tree, but you shall bury him the same day, for a hanged man is cursed by God. — Deut. 21:22–23

Why is being hung on a tree a curse? It is the public shame. When a body is buried, that shame is also buried. When it is left in public view, the criminal and their death become a spectacle. There are many ways to die with honor, like in battle for example. Such deaths may be painful and gruesome, but the valiance overtakes the brutality of the death itself. Hanging someone in public view, in the eyes of the Ancient Near East, took all of that valiance away. It wasn’t necessarily the most painful way to die, but it was the most shameful way to go because it stripped the condemned of any dignity. This occurs with one of the more villainous characters in the Bible, the infamous Haman. At the request of Queen Esther, King Ahasuerus of Persia orders Haman to the gallows because of his plot to massacre the Jews in exile.

וַיִּתְלוּ֙ אֶת־הָמָ֔ן עַל־הָעֵ֖ץ אֲשֶׁר־הֵכִ֣ין לְמָרְדֳּכָ֑י וַחֲמַ֥ת הַמֶּ֖לֶךְ שָׁכָֽכָה׃

So they hanged Haman on the gallows that he had prepared for Mordecai. Then the wrath of the king abated. — Esth. 7:10

It is interesting that Haman’s punishment is cursed death described in Deuteronomy 21. How striking is it then, that Paul’s gospel centers around God’s anointed dying the same cursed death of Haman! The Hebrew word employed here is תָּלָה talah — to hang. In Arabic, تل tala means to let down and “dangle” just as you do if you hang something. This root is also related to the common Semitic word تَلٌّ/ תֵּל tel — hill/ mound. In Greek, the word used in the Septuagint and New Testament is κρεμάννυμι which means to “hang up” or “suspend”.

Still, none of these words contain the punch that σταυρός employs. Of course, while Paul uses κρεμάννυμι and ξύλον (tree/ wood) in various places, he does so in order to utilize established scriptural language. But because Paul is writing to a gentile audience in the Roman Empire, he introduces σταυρός into the scriptural vocabulary because it would have introduced a visceral image. Crucifixion needs no introduction. It was a brutal and humiliating way to put someone to death, and it was reserved only for the lowest types of criminals. Roman citizens were protected from such a fate, even if they were given the death penalty (usually beheading).

Because Paul is highlighting the shame of Christ’s public death on the cross, he uses the word that connotes something “set up” to be visual. Σταυρός ultimately derives from the verb ἵστημι meaning to “stand”. A notable cognate to this word in English is “staff”, and its plural “staves”. If it is on a stand, it is visible to as many people as possible. It is meant to be seen, like a signpost. An example of this terminology at play is when Christ speaks about believers making their light visible to the world.

Ὑμεῖς ἐστε τὸ φῶς τοῦ κόσμου. Oὐ δύναται πόλις κρυβῆναι ἐπάνω ὄρους κειμένη· oὐδὲ καίουσιν λύχνον καὶ τιθέασιν αὐτὸν ὑπὸ τὸν μόδιον, ἀλλ’ ἐπὶ τὴν λυχνίαν, καὶ λάμπει πᾶσιν τοῖς ἐν τῇ οἰκίᾳ.

You are the light of the world. A city set on a hill (like a crucifixion on a hill) cannot be hidden. Nor do people light a lamp (λύχνον) and put it under a basket, but on a stand (λυχνίαν), and it gives light to all in the house. In the same way, let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven. — Matt. 5:14–16

The word employed here is λυχνία, which refers to something that elevates a candle (λύχνος). Similarly, σταυρός is unambiguously an exhibition. Because of its connection with ἵστημι, it is also distantly etymologically related to ἀνάστασις, the (standing upright) or “resurrection” as it is rendered in English. Therefore Paul underscores his teaching about the crucifixion, not merely in terms of suspension on a tree, but on the public exhibition of being fastened to a stake right outside the city wall. His death is a spectacle, not merely an execution by hanging.

Another interesting feature of σταυρός is its rendering in the Qur’an as صلب ṣalaba. This is interesting because there isn’t a direct Hebrew precedent to this word. It appears as though صلب is being used to directly render the Pauline σταυρός.

At its most elementary level, the root صلب refers to something becoming stiff, rigid, and robust. In two places (4:23; 86:7) it unambiguously refers to male genitalia. Many translations euphemistically translate it to loins or the backbone/ spine. Either way, it matches up perfectly with σταυρός through its connection with ἵστημι. In the remaining occurrences, it describes the crucifixion of Jesus (4:157) and then as a punishment (5:33, 7:124, 12:41, 20:71, 26:49). When describing Jesus’ death, the text cleverly disallows the Jews to boast in the crucifixion while maintaining the Pauline proclamation of a Christ “publicly presented as crucified”.

وَقَوْلِهِمْ إِنَّا قَتَلْنَا ٱلْمَسِيحَ عِيسَى ٱبْنَ مَرْيَمَ رَسُولَ ٱللَّهِ وَمَا قَتَلُوهُ وَمَا صَلَبُوهُ وَلَـٰكِن شُبِّهَ لَهُمْ وَإِنَّ ٱلَّذِينَ ٱخْتَلَفُوا۟ فِيهِ لَفِى شَكٍّ مِّنْهُ مَا لَهُم بِهِۦ مِنْ عِلْمٍ إِلَّا ٱتِّبَاعَ ٱلظَّنِّ وَمَا قَتَلُوهُ يَقِينًۢا

And for claiming that they killed the Messiah, Jesus, son of Mary, the messenger of GOD. In fact, they never killed him, they never crucified him — they were made to think that they did (شُبِّهَ لَهُمْ lit. it appeared to them so). All factions who are disputing in this matter are full of doubt concerning this issue. They possess no knowledge; they only conjecture. For certain, they never killed him. — Q. 4:157

This is a fascinating part of the Qur’an, because it is quite controversial for obvious reasons. Christian and Islamic commentators alike tend to view this as the Qur’an denying the crucifixion and death of Jesus altogether. Other scholars disagree, like Gabriel Said Reynolds who points out that the position that the Qur’an denies the death of Jesus breaks down in the original Arabic when Jesus says that God caused him to die.

مَا قُلْتُ لَهُمْ إِلَّا مَآ أَمَرْتَنِى بِهِۦٓ أَنِ ٱعْبُدُوا۟ ٱللَّهَ رَبِّى وَرَبَّكُمْ وَكُنتُ عَلَيْهِمْ شَهِيدًا مَّا دُمْتُ فِيهِمْ فَلَمَّا تَوَفَّيْتَنِى كُنتَ أَنتَ ٱلرَّقِيبَ عَلَيْهِمْ وَأَنتَ عَلَىٰ كُلِّ شَىْءٍ شَهِيدٌ

I told them only what You commanded me to say, that: ‘You shall worship GOD, my Lord and your Lord.’ I was a witness among them for as long as I lived with them. When You terminated my life on earth (تَوَفَّيْتَنِى lit. you had me die), You became the Watcher over them. You witness all things. — Q. 5:117

The verb used here is وفي and is used to describe the termination of an individual after their mission is complete. So it can mean “to pay a debt” but it can also be a punishment, and is used to describe God ending someone’s life in a purposeful way. So if the Qur’an does not deny the death of Jesus, what is it saying in 4:157? In context, it is the last statement of a retort against Jews who, after receiving the covenant on Mount Sinai, killed the prophets sent to them (4:155), slandered the Virgin Mary (4:156), and ridiculed the Christians by boasting that they killed their messiah. God’s response is to strip any satisfaction from them, and he plays an “uno reverse card” that you (the Jews) did not kill him nor did you crucify him but God raised (رَّفَعَه ُraise in authority) him to himself (4:158). Interestingly, the verb رفع raf‘a forms an inclusio between 4:154 and 4:158. In the prior case, it describes God raising Mount Sinai over the Israelites as a sign of authority. In 4:158, the surah ends that thought with the same verb to describe God raising Christ in authority, which is a Pauline construction.

…ἣν ἐνήργηκεν ἐν τῷ Χριστῷ ἐγείρας αὐτὸν ἐκ νεκρῶν, καὶ καθίσας ἐν δεξιᾷ αὐτοῦ ἐν τοῖς ἐπουρανίοις ὑπεράνω πάσης ἀρχῆς καὶ ἐξουσίας καὶ δυνάμεως καὶ κυριότητος καὶ παντὸς ὀνόματος ὀνομαζομένου οὐ μόνον ἐν τῷ αἰῶνι τούτῳ ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐν τῷ μέλλοντι·

…that he worked in Christ when he raised him from the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the one to come. — Eph. 1:20–21

So in other words, Christ’s death and resurrection is God’s victory and not anyone else’s. What is even more clever about this passage, is the construction شُبِّهَ لَهُمْ shubiha lahum — it appeared to them so. I would suggest that this phrase is a reworking of the Pauline προεγράφη ἐσταυρωμένος (presented crucified). The Jews saw a crucified Jesus who was clearly defeated. The crucifixion was very public, so much so that even Jesus’ closest disciples went away dejected by the situation. Christ’s resurrection, by contrast, was a private matter. Nobody actually witnessed the resurrection, only the empty tomb. As for the resurrected Christ, he appeared only to his apostles and then to a wider group of 500 believers (1 Cor. 15:5–8) and lastly to Paul. It is safe to assume, besides Paul, outsiders were mostly left out of the loop. From the vantage point of the Jews, they had won and could boast over it. Literally, they tripped over the stumbling block of the crucifixion. They couldn’t get over the public image of Christ crucified.

Ἐπειδὴ καὶ Ἰουδαῖοι σημεῖα αἰτοῦσιν καὶ Ἕλληνες σοφίαν ζητοῦσινἡμεῖς δὲ κηρύσσομεν Χριστὸν ἐσταυρωμένον, Ἰουδαίοις μὲν σκάνδαλον, ἔθνεσιν δὲ μωρίαν.

For Jews demand signs and Greeks seek wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles. — 1 Cor. 1:22–23

This boast of the Jews only furthers Paul’s point, not at all contradicting it. All they saw was brutality and shame, but weren’t privy to the work God did privately behind the scenes.

To wrap it up, what gives the cross (σταυρός/ صليب) power is its publicity. It is the ultimate way God subverts both Jewish and Gentile sensibility. His anointed is crushed publicly and shamefully, but his victory is in his raising Christ from the dead and sitting him at the right hand of power. This is how both the Pauline school and the Qur’anic school after them present Christ.

Before Thy Cross, we bow down in worship, O Master, and Thy holy resurrection, we glorify (Hymn of Veneration before the Cross)

As abuna nadim tarazi has always said, if the new testament is saying something different than the old testament then it is heresy. Wouldn't it be the same for quran? I wonder if Muhammad is a replacement for Judas since their name means praise?