The Lexicography of Tōrah (תּוֹרָה)

The Function of the Book of Moses and its Copies

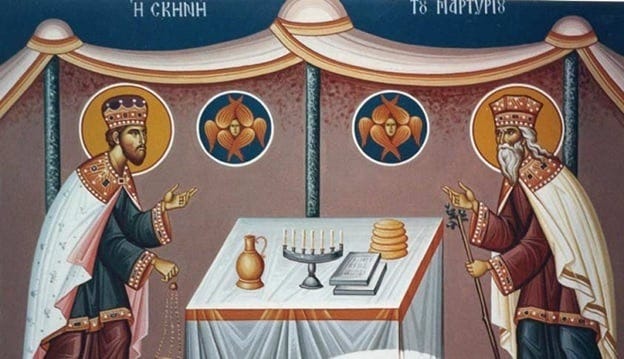

One of the more enigmatic features of the Bible is its notion of תּוֹרָה tōrah, the compendium of God’s instruction set eventually as a witness against the Israelites. This notion of witness is bolstered by the fact that the tablets containing the tōrah are placed inside of the “Tent of Witness”, or אהל מועד ’ohel mo‘ed in Hebrew. In fact, the LXX and Vulgate both link the Hebrew מוֹעֵד mo‘ed to the word עֵד ‘ed — witness/ testimony producing “ἡ σκηνή τοῦ μαρτυρίου” and “tabernaculum testimonii” respectively. Modern translations of the Bible, including the King James, tend to link it with its cognate עֵדָה ‘edah — assembly/ congregation which also shares a cognate with the Arabic word عيد ‘eid — feast. As such, we in the Anglo-sphere have become accustomed to refering to the ’ohel mo‘ed as the “tent of meeting”, made popular in part by the KJV rendering it as “Tabernacle of Congregation”. Seeing as the verb עוּד ‘oud, from the same root as עֵדָה, refers to “admonishment” I can’t help but agree with the LXX and the Vulgate in this case. This is especially the case when we take into account the warning of Deuteronomy that commands that any king who should rise up in Israel should have a copy of the book of the tōrah, so he will remember the one who gave him authority in the first place — like a sword of Damocles hanging over his head:

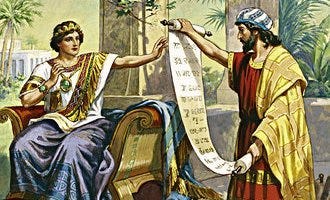

וְהָיָ֣ה כְשִׁבְתֹּ֔ו עַ֖ל כִּסֵּ֣א מַמְלַכְתֹּ֑ו וְכָ֨תַב לֹ֜ו אֶת־מִשְׁנֵ֨ה הַתֹּורָ֤ה הַזֹּאת֙ עַל־סֵ֔פֶר מִלִּפְנֵ֥י הַכֹּהֲנִ֖ים הַלְוִיִּֽם וְהָיְתָ֣ה עִמֹּ֔ו וְקָ֥רָא בֹ֖ו כָּל־יְמֵ֣י חַיָּ֑יו לְמַ֣עַן יִלְמַ֗ד לְיִרְאָה֙ אֶת־יְהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהָ֔יו לִ֠שְׁמֹר אֶֽת־כָּל־דִּבְרֵ֞י הַתֹּורָ֥ה הַזֹּ֛את וְאֶת־הַחֻקִּ֥ים הָאֵ֖לֶּה לַעֲשֹׂתָֽם׃

And it shall be at his sitting upon the throne of his kingdom, that he shall write for himself a double of this tōrah in a book before the Levite priests. And it shall be with him and he shall read in it all the days of his life, in order that he may be taught to fear Yahweh his God to keep all of the words of this tōrah and to do these statutes. — Deut. 17:18–19

Interestingly, the conventional naming of this book “Deuteronomy” seems to be tied to this verse in the Septuagint:

Kαὶ ἔσται ὅταν καθίσῃ ἐπὶ τῆς ἀρχῆς αὐτοῦ καὶ γράψει ἑαυτῷ τὸ δευτερονόμιον τοῦτο εἰς βιβλίον παρὰ τῶν ἱερέων τῶν Λευιτῶν

And it shall be when shall sit upon his authority he shall also write for himself this doubled-law into a book from the Levite priests. — Deut. 17:18

Notice the construction, δευτερονόμιον devteronomion, which is a literal rendering in the Greek of מִשְׁנֵ֨ה mišneh — second/double/copy/repition and תֹּורָ֤ה tōrah — instruction/law. The book of Deuteronomy is called as such because it is a glaring reminder that the copy of the tōrah (devteronomos) was the powerful witness against the abuse, idolatry, and injustice of the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah, and by extension, all of the kingdoms of the world. It is fitting, then, that scholarship has, in the past two centuries, dubbed the narrative spanning Genesis to 2 Kings the “Deuteronomistic History”. Indeed, Deuteronomy is the criterion that serves as the measuring stick (kanonikos) by which God functions as judge. This is powerfully echoed in the Qur’an with the word furqān and connoting the tōrah as “criterion”.

وَإِذْ ءَاتَيْنَا مُوسَى ٱلْكِتَـٰبَ وَٱلْفُرْقَانَ لَعَلَّكُمْ تَهْتَدُونَ

And when we gave Moses the Writ and the Criterion (al-furqān), that you all might be guided. — Q. 2:53

The Arabic ٱلْفُرْقَانَ al-furqān is fascinating because it has several cognates in both Hebrew and Aramaic/ Syriac. Its basic rendering has to do with “division” or setting a distinction. For example, contemporary Hebrew editions of the Old Testament use the word פֶּרֶק pereq for verse distinctions. But beyond that, this root is used several times in scripture itself. That same noun form appears in Obadiah as a crossroad (1:14) and in Nehemiah as pillage or destruction (3:1). As a verb פָּרַק paraq appears in several places meaning “to break away” and in a few occasions, to “rescue” or “snatch” (Ps. 136:24). For that reason, its Syriac counterpart ܦܘܪܩܢܐ pūrqanā is often synonymous with the Greek σωτήρ sōtēr — savior in the Peshitta, and generally refers to salvation and deliverance. This has led some interpreters of the Qur’an to translate furqān to salvation in 2:53. While this is certainly a valid translation, my opinion is that its usage in the Qur’an is unambiguously more evocative of setting a division or “distinction”.

In this sense, it is very similar to the word פְּדוּת pedūt from פָּדָה padah which also has the sense of “rescuing” on the one hand and “division” on the other. In Exodus we hear:

וְשַׂמְתִּ֣י פְדֻ֔ת בֵּ֥ין עַמִּ֖י וּבֵ֣ין עַמֶּ֑ךָ לְמָחָ֥ר יִהְיֶ֖ה הָאֹ֥ת הַזֶּֽה׃

And I am setting a distinction (pedut) between my people and between your people, for tomorrow this sign shall occur. — Ex. 8:23

In the Arabic speaking word, “Fadi” — savior — is a common name for boys and is used by Christians as an epithet for Christ.

There is clearly a commonality between being rescued and being set apart by God — and being set apart is not good news, because it keeps you in the hot seat. Translations that merely render furqān as “salvation” lose the bite that the Arabic original has. God’s indignation against the Sons of Israel in the Qur’an would not carry the sting that it has in Surat al-Baqarah if there was no furqān in the Tōrah held against them — their sword of Damocles.

yarah & wara

The word tōrah is from the Semitic triliteral yod-resh-he and appears in several different ways throughout the scriptures. In Hebrew, the verb יָרָה yarah literally means “to throw” or to “cast”. It is used to describe the shooting of arrows in an archery setting. Figuratively, it has the sense of “showing” something or making something appear/evident. In this sense, it can also mean “to lead” — hence we have the connotation of “to teach”. A similar function can be found with the root למד lmd which originally connoted a shepherd’s staff, but eventually referred to pedagogical instruction via guidance, as a shepherd leads his flock. So the Hebrew verb לִמֵּד limmed means “to teach”, which is the piel form of לָמַד lamad — to learn. The root למד transformed into a verbal noun takes a tāw at the front of the construction, giving us תַּלְמוּד talmūd — teaching. Likewise, ירה as a verbal noun gives us תּוֹרָה. This is a common construction in Semitic languages, especially in Islamic theology. Take for instance the Takbir (تَكْبِير) which references the proclamation “Allahu Akbar” from the word كَبِير kabirmeaning “great” or “mighty”. Another famous example is Tawḥid (تَوْحِيد) which is a proclamation of God’s “oneness” from the verb وَحَدَ waḥada — to unify. The transformation of the yod ( י) in ירה to the wāw (ו) in תורה testifies to the fluidity between the two letters in Semitic languages. It is a common pattern, seen especially in cognates from Hebrew to Arabic. The root wāw-rā-yā in Arabic connotes “hiddenness and burial” on the one hand, and “ignition” on the other.

This appears to have the opposite connotation to its Hebrew counterpart, which is actually a common occurrence between these languages. Like yarah and wara, the root ayin-lamed-mem can either mean “to teach” (as in Arabic) or to “hide” (as in Hebrew). As I demonstrated in a recent article about that root, these two functions complement each other rather than contradict. In short, for something to be “taught” it needs to be “hidden” first — at least from the vantage point of the student. That is where the “prophet” comes in, who reveals the hidden matters (mystērion) of the deity. That is why in the Bible, revelation is an uncovering (apokalypsis). As we hear from Surat Al-‘Alaq,

ٱقْرَأْ وَرَبُّكَ ٱلْأَكْرَمُ ٱلَّذِى عَلَّمَ بِٱلْقَلَمِ عَلَّمَ ٱلْإِنسَـٰنَ مَا لَمْ يَعْلَمْ

Recite! And your Lord is most noble, who taught by the pen. He taught mankind what he did not know. — Q. 96:3–5

Thus, the pedagogy of the Tōrah is contingent upon the mouthpiece nabi(prophet) who makes the will of the deity known. In the Ancient Near East, this was principally the responsibility of the priest who was privy to the “secret knowledge” of the divine, hidden behind the veil that only he (as a consecrated minister) could enter. This can be seen by the terminology of the Essenes, who followed a figure call the mōreh ṣedeq which means the “Teacher of Righteousness”. Mōreh is the nominalized form of yarah, and its priestly function is evident from the Essene commentary on Habakkuk found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. In the commentary, it says of the mōreh ṣedeq that he is the one “to whom God made known all the mysteries of the words of his servants the prophets”. The terminology is clearly a play on Habakkuk 2:18 which critiques the worship of idols, which function as teachers of lies (mōreh šaqer). To top it all off, the Essenes (including their leader) are believed to have been priests themselves who had somehow been estranged from the Jerusalemite establishment.

The scandal of the Hebrew Bible was in the collapse of the traditional socio-political structure of the Ancient Near East. The priest-king duo was completely dismantled and dismissed, in favor of an all powerful gibbor (mighty warrior) whose arrogance and might would out-do even the most egregious opponents. Deities of wood and stone can be smashed, and all kings and tyrants pass away — but the scriptural deity of rūaḥ and katūb is everlasting. Those two mechanisms, of breath and writ, are critical because even if every katūb was destroyed, the debarim (words) can be memorized and thus intoned as in a Muslim ḥāfiẓ. With the dismissal of the priest-king and the palace-temple complex, the Tōrah becomes the central authority — accessible beyond palace and priestly elite. In this sense, Tōrah becomes “pedestrian” in that it is intended to be learned, recited, and lived by the people, rather than being confined to royal or priestly elites.

כִּֽי־קָרֹ֥וב אֵלֶ֛יךָ הַדָּבָ֖ר מְאֹ֑ד בְּפִ֥יךָ וּבִֽלְבָבְךָ֖ לַעֲשֹׂתֹֽו׃

For the word is very near you, in your mouth and in your heart that you should do it. — Deut. 30:14

Moses, the Pedestrian Tōrah, and Aaron

The link between the pedestrian nature of the Tōrah in the Nebi’im and the character of Moses (who wanders on foot in the wilderness) is demonstrable from his name and function in the text. The name משֶׁה mošeh is linked to the verb מָשָׁה mašah — to pull out in Exodus 2:10 when Pharaoh’s daughter pulls him from the water. The discussion usually ends there, but it is worth pointing out that this root in Arabic has the broad sense of “walking” or “pedestrian” — as brilliantly employed by Iskandar Abou-Chaar in his book Rereading Isaiah 40–55 as the Project Launcher for the Books of the Law and the Prophets (p 143).

This two-fold understanding of his name covers the itinerary of his character, who (with the power of God) draws his people out of Egypt and leads them on foot into the wilderness. It is Moses and Aaron who must travel to the Pharaoh and appeal to him directly, just like how the nebi’im had to appeal in person to the kings in their own day. Moses becomes the walking instruction to such a degree that God declares him to be “God” of Pharaoh, with Aaron has his prophet.

וַיֹּ֤אמֶר יְהוָה֙ אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֔ה רְאֵ֛ה נְתַתִּ֥יךָ אֱלֹהִ֖ים לְפַרְעֹ֑ה וְאַהֲרֹ֥ן אָחִ֖יךָ יִהְיֶ֥ה נְבִיאֶֽךָ

And Yahweh said to Moses, See I make you God to Pharaoh and Aaron your brother shall be your mouthpiece (prophet). — Ex. 7:1

Virtually every translation tries to undermine the force of this passage. They will either say (a god) or (like God), but the original is quite powerful: Moses is God to Pharaoh in the sense that he functions as God would function. The scriptural deity temporary gives Moses divine authority, in a similar way to how the New Testament bestows that divine authority to Jesus — the difference being that Jesus was raised in authority over all of the nations of the earth (1 Cor. 15:24–28) not just one geographical location. Moses, as “God over Pharaoh”, functions as the itinerant word that will later be consigned to a book as a copy (mišneh), tying it in with the devteronomion discussed above.

It is also interesting that Aaron becomes the prophet (nabi’) before he becomes a priest. The second part of the Old Testament, the Nebi’im, will reverse that by making the priests (like Jeremiah and Ezekiel) into prophets since their respective sanctuaries are destroyed and their priestly activity is voided. Thus we have the twofold mechanism of the prophetic literature: the word (dabar) actualized by Moses and the prophet (nabi’) actualized by Aaron. This proceeds and succeeds the conventional priest-king mechanism that breaks down throughout 1 Samuel-2 Kings. By antiquating the radical literature of the Hebrew prophets, the five books of Moses make a clear point that the priest-king complex is decidedly not the will of the scriptural deity and that the dabar, whether in katūb or rūaḥ, is the highest authority as is crystal clear from the book of Deuteronomy. Why do you think King Josiah tore his garments after Hilkiah found the book of the Law buried (remember the Arabic?) and forgotten in the Jerusalem temple? Hilkiah had to draw it out (remember the Hebrew?), but by that point it was already too late as we hear towards the end of 2 Kings.

In summary, the Tōrah antiquates and upholds the radical literature of the prophets, making it clear that the palace-temple system was never the will of the scriptural deity. Instead, divine authority resides in the dabar (word), whether written (katūb) or spoken (rūaḥ). Moses’ name (mošeh) signifies movement and oral instruction. He leads the people on foot, embodying the Tōrah in motion. This contrasts with later institutionalized priestly authority, who were forced into prophetic roles when their temples were destroyed — making it clear that the itinerant word was God’s pedagogical will throughout all of scripture. This is the reason why Jeremiah prophesies of an eschatological moment where all of the nations will follow the Tōrah, not in the written code evocative of the priestly establishment, but in their hearts, as the Tōrah dwells among them, itinerant and pedestrian (Jer. 31:31–34).

Where do you think Paul got it from?