For the past year, I have greatly benefited from the witness of the lexicographical work employed by the Very Rev. Fr. Marc Boulos in his podcast The Bible as Literature and his weekly bulletin tied to the ministry of his parish. It was from both of these outlets, as well as his powerful book DARK SAYINGS: Diary of an American Priest, that I began to appreciate the direct application of this discipline in the elucidation of what he calls “The Abrahamic Family” of scrolls (i.e. the Old & New Testaments plus the Qur’an).

I have spoken at length about the value and necessity of lexicography, which is incredibly powerful with respect to Semitic languages because of their triliteral system. This renewed discipline furthers the work of the Very Rev. Dr. Paul Nadim Tarazi and his student Iskandar Abou-Chaar who have stressed the functionality of Semitic roots in scripture, often using lexicographical and comparative methods.

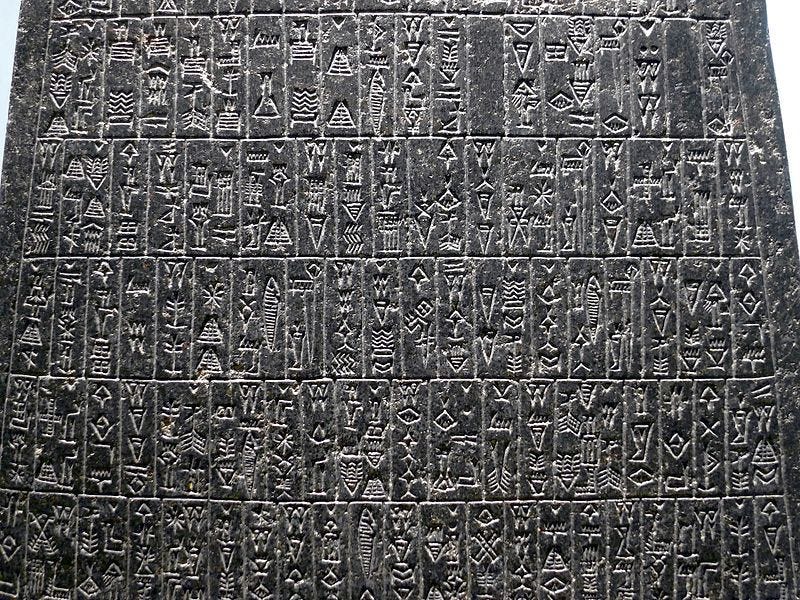

The study and comparison of Semitic triliterals is made possible only by the highly intuitive nature of the consonants. While we take it for granted now, the adoption of phonetic consonants in writing was a major historical breakthrough for literacy. The first Semitic language on the scene was Akkadian, which adopted the Sumerian cuneiform script. This style was the standard writing system for centuries (technically active as late as the 2nd century CE), and was used to record the literature of the Hittites, Babylonians, Assyrians, the early Canaanites, and Persians (just to name a few).

While it was widespread, it wasn’t the most convenient exercise. When a nation of maritime Canaanites, known in history as the Phoenicians, needed to catalog trading receipts, it became apparent that a quicker and more versatile script was in order. The result was a clever system that was both pictographic and phonetic, ensuring that simple exchanges could be legible to foreigners throughout the Mediterranean. Each consonant was represented by an icon depicting an object whose name started with the corresponding sound. It is a wonderful didactic tool and reminds me of those children’s books that go like: A is for apple, B is for bear, etc. It is also reflective of a literary device employed in the poetic sections of the Ketubim, like the acrostic structure of Psalm 119.

Anyways, the Phoenician alphabet (the mother of nearly all Semitic and Indo-European scripts) originally went like this:

𐤀 (’alef) means ox (notice the horns), as it does in Hebrew אֶלֶף ’elef. This letter was incorporated in Greek as “alpha”. That being said, this should not be confused with the letter “A” as we have it in English because it is not a vowel. It is rather a consonant best understood as the “glottal” stop, which refers to the phenomenon of “stopping” airflow in pronouncing an expression. A good example from English is the pause in “uh oh”. It’s difficult to detect when the glottal stop is at the beginning of the word but it can be clearly heard when it appears in the middle. Take, for instance, the word messenger: מַלְאָךְ (pronounced mal-’ak). It is not malak as in one breath but is interrupted by the alef. In Arabic, the alif functions a bit differently. Instead of being a glottal stop, it is completely silent and merely serves to lengthen the vowel applied to it. The glottal stop is instead indicated by the diacritic ء (hamza). So if we take the word الْقُرْآنُ al-qur’ān we notice some interesting features in the diacritics. The letter آ alif here has a little line above it — that is the “hamza” in action, as it is often placed above or below its letter (could be alif, waw, or ya) depending on the situation. In the transliteration, the apostrophe represents the glottal stop breaking up the word and the line over the “a” represents the alif lengthening the vowel. An American might pronounce it as Koran or Quran, but an Arabic speaker will include the “glottal stop” and say “qur-’an”.

𐤁 (bet) meaning house. In Hebrew, we of course have בַּיִת bayit with the same function. Likewise in Greek, we have “beta” although in Modern Greek we would pronounce it “vita”.

𐤂 (gimmel) represents the “camel”. In Hebrew we have the letter ג gimel which is similar to גמל gamal — camel. In Arabic, the word is جَمَل jamal but the letter is called “jeem”. In Greek, this was incorporated into the letter gamma.

𐤃 (dalet) refers to a door. In Hebrew, the word for door is דֶּלֶת delet and in Arabic the root د-ل-ل (dal-lam-lam) often has the connotation of guidance, indication, proof, or showing the way. In Greek, we have the letter “delta”.

𐤄 (he) is often associated with the concepts of “opening” on the one hand, and jubilation on the other. It is speculated that the original form of the pictograph depicted a figure with raised, outstretched arms (in the act of rejoicing). In the South Arabian script, we have 𐩠 which was later incorporated into Ge‘ez as ሀ. This makes sense linguistically, as the Hebrew word for rejoicing (or making celebratory noise) is הלל halal beginning with the same letter. Similarly, the root هـ ل ل in Arabic signifies praise, but also an announcement or calling out. This is very interesting because this Semitic root in general also has the sense of “shining” or illumination. With this in mind, we can readily understand the connection to the “window” in the pictograph. In Greek, this letter was reworked into epsilon. Notice how “E” is just the letter 𐤄 horizontally flipped. As was the case with alef, we can’t fall into the trap of viewing ה as a vowel just because it was incorporated as such in European borrowings. ה merely represents the soft breathing, which is left up to diacritical marks in Greek.

𐤅 (waw) represents a hook. This makes sense because, in Semitic languages, this character is used for the word “and” which connects different words together. Hebrew, being very closely related to Phoenician, also uses the word וָו waw for hook. In Greek, this letter became upsilon which appears identically as Υ.

𐤆 (zayin) functions as “weapon” in Semitic languages. While this function is absent in Biblical Hebrew, there are occurrences of the word זַיִן referring to any instrument of combat. In modern Hebrew, it has taken on a phallic connotation in contemporary slang. In Greek, we have the letter zita.

𐤇 (ḥet) refers to a fence. A direct Arabic counterpart to this word is the construction حوط ḥwṭ which refers to an enclosure. This letter formed the basis of ita (H) in Greek.

𐤈 (ṭet), as the image greatly suggests, is representative of a spinning wheel. The verbal form of this root is present in Hebrew as טָוָה ṭawah — to spin. In Greek, this letter became thita and its form (Θ) greatly resembles the Phoenician style.

𐤉 (yod) represents the hand, which is present across all of the Semitic languages. In Hebrew, we have the word יָד yad and in Arabic we have يَد yad. This is an interesting letter because it is often fluid with waw. A clear example is the noun תּוֹרָה torah — instruction which is from the verb ירה yarah — to instruct. There, the yod (י) turns into a waw (ו). In Greek, this letter became iota.

𐤊 (kaf) refers to the palm of one’s hand, as it does in Hebrew (כַּף). Likewise in Arabic, كَفّ kaff has the same function. In Greek, this letter became “kappa”.

𐤋 (lamed) is representative of the shepherd’s staff or goad. In Hebrew, the root ל-מ-ד refers to teaching or guiding. The word for “goad” is מַלְמָד malmad, the nominalized form of the root. This letter became “lambda” in Greek.

𐤌 (mem) is indicative of “water” or מַיִם mayim in Hebrew. In Arabic, it is مَاء. This letter formed the basis of the letter “mi” in Greek.

𐤍 (nun) refers to a “fish” in Phoenician, as it does in Arabic (نون in the Qur’an). In Hebrew, the word for fish is דָּג dag taking after the Canaanite fish deity Dagon. In Greek, this letter became “ni”.

𐤎 (samek) represents a “pillar”. The verb סָמַך samak in Hebrew means to lean upon, support, or uphold. In Arabic, the root سمك refers to something raised. In Surah 79:28 of the Qur’an, it functions as a ceiling. In Greek, samek corresponds to the letter ksi (Ξ).

𐤏 (‘ayin) means “eye” in the Semitic languages, and the pictograph is clearly representative as such. As was the case with alef, this letter is not to be thought of as a vowel despite it being the ancestor to our letter “o” via the Greek o-mikron (small “o”). ‘Ayin is a guttural consonant, pronounced at the back of the throat. As such, it is difficult for non-native Semitic speakers to pronounce it correctly. Modern Hebrew, taking its phonology from European languages, virtually ignores this feature of ‘ayin and essentially treats it as alef. In Arabic, this letter merged into two distinct characters. While there is “ayin”, there is also the letter ghayin which introduces a harsher guttural sound. This sound was likely present in the Hebrew pronunciation of ‘ayin with some of its vocabulary because of the tendency of the LXX to transliterate the sound with a gamma (Gaza עַזָּה and Gomorrah עֲמֹרָה being prime examples).

𐤐 (fe) represents the “mouth”, which is a common construction in Semitic languages. It either appears as an “f” sound or a “p” sound, and in Hebrew, alternates between the two. In Greek, this letter became Π (pi).

𐤑 (ṣade) refers to a fishing hook. In Hebrew and Arabic, it is used to communicate both hunting and fishing — צוּד ṣud meaning to “hunt” and צַיִד ṣayid referring to the “game” that is caught. While this letter was not preserved in Greek, archaic writings in the language had the letter sampi ϡ which likely corresponds to ṣade.

𐤒 (qof), not to be confused with kaf (pronounced in the front of the throat) refers to the eye of a needle. Alternatively, it could also represent a monkey since this is the letter function of קוֹף qof. This letter was not incorporated directly into Greek, but its form bears a striking resemblance to the letter fi (φ).

𐤓 (resh) refers to a “head” in Semitic languages — Hebrew has רֹאש rosh and Arabic has رَأْس ra’s. In Greek, this letter became “rho”.

𐤔 (shin) is representative of the “tooth” (שֵׁן), as the “points” would suggest. It became the letter sigma (Σ) in Greek, although it was horizontally flipped 90 degrees.

𐤕 (taw), the last letter of the Semitic abjad, represents a mark or cross. In Hebrew, there is the word תָּוָה tawah which is used when God gives Cain his signature mark. This letter was incorporated into Greek as the letter tau (τ).

Importance of Alphabet

Now that we have studied the letters of the abjad, it would behoove us to underline the importance this had for scripture. While it was undoubtedly introduced for practicality in a maritime trading context, having an intuitive language that could be readily learned and disseminated was crucial for scripture to have the power that it had. Scripture was meant to be read and proclaimed, not only by a group of scribal elites or priests but to all nations (Ps. 117:1). This alphabet took a complicated writing system, and introduced something that didn’t require specialization to engage with.

An interesting parallel is the creation of the Korean alphabet (Hangul) in 1443 by King Sejong the Great to increase literacy among his subjects, who had been relying on the non-native Chinese alphabet (Hanja), which contained hundreds of complicated characters that were awkwardly adapted for Korean use.

Like Phoenician, Hangul was very intuitive. It was phonetic, with one sound per consonant with vowels that visually indicated where to direct the sound. For example, the vowel ㅏpoints “outward” and so has an “ah” sound. Conversely, ㅓpoints inward and has an “uh or eh” sound. In other words, the vowel is directed inward rather than projected outward. This makes reading quite engaging. Let’s take the word “han” and see its construction. First, we have the letter ㅎ (h) which sits upon the letter ㄴ(n). In the middle, we have the vowelㅏ(ah). So all together we have 한 han. The consonantal structure, like Semitic languages, makes up the main figure. The vowel symbol merely shows you where the sound in the middle of the consonants goes. To my knowledge, the Japanese alphabet has a similar history and intentionality.

In conclusion, studying the Phoenicians (and similar cultures) is crucial to understanding Semitic lexicography. Part of what makes it work is the writing system. While Semitic languages, like their broader Afro-Asiatic family, use the consonantal root system, it would be more difficult to detect without such a robust system. It works for the language better than Cuneiform which was introduced by the non-Semitic Sumerians.

The Phoenicians were so influential to the Mediterranean that their writing system was adopted by the Latins and Etruscans as well as the Greeks who would later introduce it to the Slavs. The Latins were responsible for transferring it to the Celts, Gauls, Germans, and Britons. Even their form of government was influential. The Carthaginians (North African descendants of the Phoenicians) had a republican form of government headed by a consul called a 𐤔𐤐𐤈 shofeṭ much like the scriptural “judges”. The name Carthage is a corruption of the original 𐤒𐤓𐤕 𐤇𐤃𐤔𐤕 qrt ḥdšt — new city referring to the transfer from Tyre to North Africa. The root 𐤒𐤓𐤕 is related to the Hebrew קִרְיַת qiryat — town and 𐤇𐤃𐤔 calls to mind חֹדֶש ḥodesh — new/ month. The famous military leader, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋 𐤁𐤓𐤒 ḥaniba‘al barqa is linked to the Hebrew words חֵן ḥen — grace, בַּעַל ba‘al — husband, master, Baal, and בָּרָק baraq — lightning. No wonder the Romans hated the Jews so much! They were just like their archnemeses, the Carthaginians!

The irony of this all is that the Greeks viewed these people (as well as the Arameans to the north) as Barbarians that needed to be inculcated with the Greek language and her literature. All of that literature and philosophy was written in a script that came directly from a Canaanite culture. If that isn’t arrogance, I don’t know what is.