Unity and Community (notes on the Nicea Commemoration)

Nicea & the Myth of Unity

Shortly after the election of Cardinal Robert Prevost to the Papacy (as Leo XIV), it was announced that he would join the Ecumenical Patriarch, Bartholomew, in an ecumenical commemoration of the 1,700th anniversary of the Council of Nicea. The ceremony took place a few days ago (November 28, 2025), and occurred next to the ruins of a basilica supposedly built on the location of the council. Its exact whereabouts are unknown, and the basilica in question is underneath the lake in Iznik. I wrote about the irony of this in my article back in May. Time is God’s undefeated weapon. Impermanence is how he rescues creation from evil.

ויאמר יהוה לא־ידון רוחי באדם לעלם בשגם הוא בשר והיו ימיו מאה ועשרים שנה

And Yahweh said ‘my breath shall not suscicate man indefinitely, for indeed he is flesh and his days shall be one hundred and twenty years’ (Gen 6:3)

The Nicene Council is, of course, the great romanticized synod of old in which all (lowercase) orthodox Christians look back to in a sort of ecclesial nostalgia. This touches on the mythologized story of a united church before the fragmentation and scattering of the church during the course of the middle ages and renaissance. A close reading of history definitely complicates that narrative. The synod that was convened in Nicea at the behest of Constantine in 325 was not originally the ecumenical unifier it would become regarded as in the successive centuries. The Patriarchate of Seleucia-Ctesiphon (the twin-city capital of the Persian Sasanid Empire in Iraq) was largely ignorant of the council until it received and approved a recension of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed in 410.

Throughout the fourth century, the labels homoousion (same essence) and homoiousion (similar essence) remained controversial. This was even true among “orthodox” figures of the time, like future saints Cyril of Jerusalem and Hilary of Poitiers, who acknowledged broad agreement with Nicea but avoided the “essence” debates because such terms were absent from the scriptures. In fact, St. Cyril’s Catechetical Letters are a prominent example. He presents his catechesis around the creed, but leaves out the word homoousioscompletely. When discussing the Holy Spirit, he writes:

And it is enough for us to know these things; but enquire not curiously into His nature [ousia] or substance [hypostasis]: for had it been written, we would have spoken of it; what is not written, let us not venture on ; for it is sufficient for our salvation to know, that there is Father, and Son, and Holy Ghost. (Catechetical Lectures XVI:24)

While Cyril and Hilary were canonized as saints, most of those who disagreed with the verbiage around homousios and homoiousios were maligned as “Arians” or “Semi-Arians” even though their positions had nothing to do with Arius. As such, Eusebius of Nicomedia (who famously baptized Constantine on his deathbed) has been retroactively labeled a Semi-Arian. This is also true for figures such as Ulfilas, the so-called Apostle to the Goths, and the translator of the Holy Scriptures into the Gothic language. Far from ending the debate, councils addressing the “ousia” question continued decades later in the councils of Serdica (343), Seleucia [the one in Anatolia, not Mesopotamia] (358), and Constantinople (360). The aforementioned council of Seleucia rejected both homousios and homoiousios and also repudiated a proposed third option (anomoeonism) and presented a creed that mirrors Nicea, just without the ousia clause. St. Cyril seems to have broadly been supportive of this council. The next one, Constantinople was a bit more controversial. In lieu of saying nothing at all, this synod used the word homoion without including the word “ousia”, merely saying that the Son was “like” the Father who begot him [ὅμοιον τῷ γεννήσαντι αὐτὸν Πατρὶ]. In this sense, it more closely reflects the Semitic functions כן kn and משל mšl than ousia which cannot function in Semitic by virtue of the fact that a present form of “to be” does not and cannot work in the language.

Even then, the creed of Constantinople (360) still operated within the presupposition of the ousios debates that Θεός needed to explained in terms of Hellenistic essentialism rather than Semitic functionality. In other words, the simple statement of the Apostle Paul that Christ was God over all (Romans 9:5) couldn’t be received in a simple, straightforward way. It had to become a philosophical debate. For Paul it was simple, because he meant that the risen Christ, at the right hand of the Father, functioned as judge and therefore functioned as God. This is no different than the way that Moses functioned as God to Pharaoh. Despite translations uncomfortable with the verse, it does not say Moses was “like God” to Pharaoh. It says that he shall be God to Pharaoh (Ex 7:1). This is because the term Θεός is functional, not essential. I strongly believe that the likes of St. Cyril, and perhaps several of those later maligned as “Semi-Arians” understood this. With the triumph of the Second Ecumenical Council (Constantinople I, 381), and under the influence of Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers, the Roman Imperial Church became increasingly tied to Hellenistic philosophical terminology. Terms such as ousia and hypostasis were standardized to articulate Trinitarian dogma, embedding Greek metaphysical categories into Christian theology, departing from Scripture’s functional terminology.

It was Constantinople I (381) that codified homoousios as a legally binding doctrine under imperial sanction. As such, the descent into philosophical absurdity reached its apex. The Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon were not about the divinity of Christ per se, but about how the divinity and humanity operates within the person of Christ. Gone was the simple functionality of Christ on the judgment seat in Paul’s letters! Now we were grumbling about the metaphysical makeup of Christ, like Pharisees debating ad naseam about the limits of the Mosaic Law. And then the next councils in the Roman canon (the Oriental Orthodox had jumped ship at this point) unraveled into debates, not about Christ’s natures but about his “wills”.

As I have written before, the chaos sparked by the aftermath of these specifically Christological controversies in the Christian East directly led to the revelation of the Qur’an, in which Christian and Jewish institutional sectarianism is at the forefront. The paradigm presented in the Qur’an reflected apocalyptic literature around the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon which, since the Council of Ephesus, was no longer in communion with the rest of the Christian world.

One of the most vocal East Syriac voices from this period was Bar Penkaye, who lamented on the church’s fragmentation from the controversies:

There were, indeed, many synods even before Nicaea, but they were not ecumenical, and were not convoked in order to make a new creed, but only for the purposes indicated indicated above. But once peace was restored and Christian kings had taken over the reins of government of the Romans, then vice and scandal entered the Church, and synods and sects multiplied, because every year someone invented a new creed. Security and peace led to many evils. The lovers of glory stirred up troubles unceasingly, using gold to obtain the consent of kings, so they could play about with them like little children. All this happened among the Romans. (Book of Main Points, book 15)

The irony today is that the Council of Nicea is celebrated in the name of unity, but it was precisely that council that set the stage for the endless disunity that followed throughout church history. If unity is to be celebrated, Nicea is not the light on the hill.

But that is precisely the sin of the people according to the Abrahamic Scrolls. They celebrate unity and community when they (in their imaginations) wield the power to include and exclude. “Unity” becomes a Platonic ideal, and something to continuously distort in their own image, but shared only with those they judge to be worthy. But like the prophetic witness of the scriptures, God is the one who strikes the shepherd and scatters the sheep. He gathers his qahal (convoked assembly) at the sound of his qōl (voice). Both qōl and qahal are from the same triliteral in the Semitic languages. An ecumenical gathering in 2025 to reminisce on a nostalgic unity that never really existed is nothing more than “making a show of the flesh”, to channel Paul’s critique of the Jerusalem elite. Nicea was far from being a triumph for the Pauline gospel.

It’s actually quite visceral in the Qur’an. While the Christian elites descended into deeper fragmentation from these debates, God is said to have fueled this fragmentation. One who has read the Hebrew prophets shouldn’t be surprised by this.

وَمِنَ ٱلَّذِينَ قَالُوٓا۟ إِنَّا نَصَـٰرَىٰٓ أَخَذْنَا مِيثَـٰقَهُمْ فَنَسُوا۟ حَظًّۭا مِّمَّا ذُكِّرُوا۟ بِهِۦ فَأَغْرَيْنَا بَيْنَهُمُ ٱلْعَدَاوَةَ وَٱلْبَغْضَآءَ إِلَىٰ يَوْمِ ٱلْقِيَـٰمَةِ ۚ وَسَوْفَ يُنَبِّئُهُمُ ٱللَّهُ بِمَا كَانُوا۟ يَصْنَعُونَ

And with those who say ‘We are Christians’ We took their covenant; and they have forgotten a portion of that they were reminded of. So We have stirred up among them enmity and hatred, till the Day of Resurrection; and God will assuredly tell them of the things they wrought. (5:14)

As Fr. Marc Boulos has said in his recent homily on the feast day of St. Andrew the First Called, community is rebellion. Yes, this hurts the American ethos, which has running through its veins the worship of dēmokratía (the rule of the people). But community is simply idolatry. Nicea is a milestone for the abstract Platonic form of “Christianity” but it has nothing to do with the gospel. It is the false god of one’s community that sees itself indebted to the councils of old, but in which they are merely participating in a mythology carefully crafted by empire as part of its national narrative. That is why narrative is also anti-scriptural. In Arabic, this is the word ḥadith and there is only one ḥadith according to the Qur’an!

A Lesson from the Past

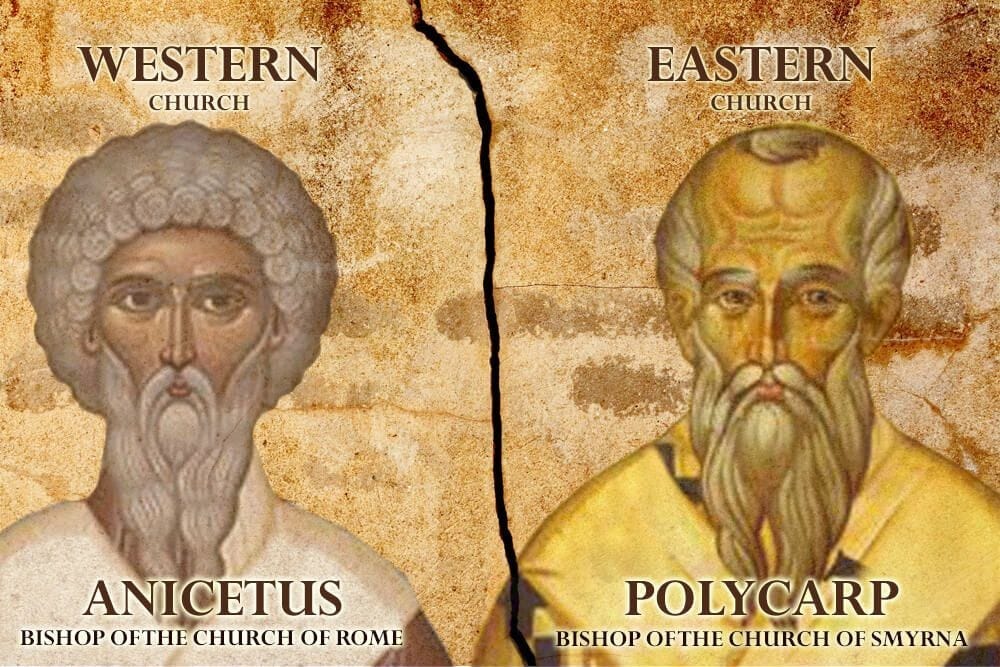

Anicetus and Polycarp, representatives of the Easter Controversy

The irony with Nicea being perceived in terms of “unity” also comes to a head with regards to its treatment of the different paschal traditions practiced by the churches in Rome and the churches in Asia Minor. By the early second century, the tension between the differing traditions came to a head. The churches of Rome commemorated the death of Jesus as happening on the day after slaughtering of the Passover lambs (the 14th day of the month of Nisan). The churches of Asia, on the other hand, commemorated Jesus’ death on 14 Nisan. This meant that Pascha could land on any day of the week in the Asian churches, whereas the Roman churches fixed Pascha on the first Sunday after 14 Nisan. This liturgical difference threatened excommunication between the two groups on several occasions in the second century.

In his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius of Caesarea records a story of Polycarp (a bishop in Asia) traveling to Rome to meet with Pope Anicetus in order to soften the tension between them. According to Eusebius, Polycarp appealed to this tradition by saying that it was handed down to them by St. John the Apostle himself. On the other hand, both bishops acknowledged that the Roman tradition was established by Sts. Peter and Paul, the two martyrs in Rome (cf Rev 11:3–10). Since both traditions were equally apostolic, the two bishops agreed to respect each other’s tradition and the the tension was temporarily loosened. This resonated with the message of Paul’s letters that the Eucharistic table of fellowship is not the place to impose uniformity. It is eclectic and heteroclite. A Jew, fully entrenched in his traditions, is expected to approach the Eucharistic table with a Gentile without imposing Judaism on the Gentile. To impose uniformity is to betray the witness of Paul.

This meeting is thought to have occurred around 154. Decades later in 189, Pope Victor completely reneged on his predecessor and actually excommunicated the Asian churches over this difference in tradition. It had to be resolved with letters from various other bishops affirming the apostolic origin of the practice, with Irenaeus of Lyon (while agreeing with Victor’s position) still coming to the defense of the Asian churches. After this, tensions were still present by relaxed until the fourth century.

Then in the letter of the Synod of Nicea to Egyptians, the bishops of the council called for a common ecumenical tradition for celebrating Pascha, corresponding to the Roman tradition.

We also send you the good news of the settlement concerning the holy Pascha,namely that in answer to your prayers this question also has been resolved. All the brethren in the East who have hitherto followed the Jewish practice will henceforth observe the custom of the Romans and of yourselves and of all of us who from ancient times have kept Easter together with you. Rejoicing then in these successes and in the common peace and harmony and in the cutting off of all heresy, welcome our fellow minister, your bishop Alexander, with all the greater honour and love. He has made us happy by his presence, and despite his advanced age has undertaken such great labour in order that you too may enjoy peace. (Synodal Letter to the Egyptians)

From then on, the practice of the Asian churches was dubbed Quartodecimanism and regarded as a heresy. A heresy that was propagated by the Apostle John and St. Polycarp!

The connection with John isn’t accidental either. The canonical edition of the New Testament actually harbors the tension of both Paschal traditions. The gospels of Mark, Luke, and Matthew all record Jesus being crucified on 15 Nisan (the day after the slaughter of the lambs). The last supper is presented as a Passover meal. In John, by contrast, the crucifixion takes place on the day the lambs were slaughtered, which means that it would be before the Passover meal could take place.

ἦν δὲ παρασκευὴ τοῦ πάσχα ὥρα δὲ ὡσεὶ ἕκτη καὶ λέγει τοῖς Ἰουδαίοις Ἴδε ὁ βασιλεὺς ὑμῶν. οἱ δὲ ἐκραύγασαν Ἆρον ἆρον σταύρωσον αὐτόν λέγει αὐτοῖς ὁ Πιλᾶτος Τὸν βασιλέα ὑμῶν σταυρώσω ἀπεκρίθησαν οἱ ἀρχιερεῖς Οὐκ ἔχομενβασιλέα εἰ μὴ Καίσαρα. τότε οὖν παρέδωκεν αὐτὸν αὐτοῖς ἵνα σταυρωθῇ Παρέλαβον δὲ τὸν Ἰησοῦν καὶ ἀπήγαγον·

Now it was the day of Preparation of the Passover. It was about the sixth hour. He said to the Jews, “Behold your King!” They cried out, “Away with him, away with him, crucify him!” Pilate said to them, “Shall I crucify your King?” The chief priests answered, “We have no king but Caesar.” So he delivered him over to them to be crucified. (Jn 19:14–16)

In other words, the Synoptics (I hate that word, but it’s the only adjective that works) reflect the “Roman” tradition and the Gospel of John reflects the Asian one. It is codified right in the canon of the New Testament, and according to David Trobisch’s book On the Origin of Christian Scripture (pp 21–30), the second century debate over the “Easter Controversy” could have been one of the background events that influenced the shape of the canonical New Testament.

Be that as it may, if the New Testament preserves the tension within its canon, why for the love of the Almighty has the post-Nicene church been so reticent to accept tension? Since Nicea, ecclesial communion apparently necessitates complete uniformity in doctrine (and sometimes practice) in order for one to participate at the Eucharistic table. It is a new form of Judaizing, only using the local customs of one set of Christians against the customs of the other. This is why a full reunion between the Roman Catholics and the Eastern Orthodox will never happen. It is also why a full reunion between the Eastern Orthodox and the Oriental Orthodox will never happen. You might get some groups who switch episcopal allegiances, as what happened regarding the 23 particlar Eastern Catholic churches. But the schisms at large will never be healed, because the sins of the Judaizers flow through the veins of the church. As Paul said, “a little leaven leavens the whole lump” (1 Cor 5:6). Bad yeast, even if small, will spread like a malignant tumor and corrupt the whole system. Christians that broadly agree, but are admittedly not absolutely identical in doctrine, cannot celebrate the Eucharist together and will never be able to do so without doctrinal concession. So, because of Nicea, Christian unity is impossible and to pontificate about unity while celebrating Nicea, is merely a spectacle reveling in nothing but nostalgia for a time that never was.