דברה (w/ excursus on the Oracula Sybillina)

In Daniel 2:30, there is a striking occurrence of the root ד-ב-ר (dalet-bēt-resh), which continues to add depth to connections impossible to detect in translation. At the end of the passage, we hear:

וַאֲנָ֗ה לָ֤א בְחָכְמָה֙ דִּֽי־אִיתַ֥י בִּי֙ מִן־כָּל־חַיַּיָּ֔א רָזָ֥א דְנָ֖ה גֱּלִ֣י לִ֑י לָהֵ֗ן עַל־דִּבְרַת֙ דִּ֤י פִשְׁרָא֙ לְמַלְכָּ֣א יְהֹודְע֔וּן וְרַעְיֹונֵ֥י לִבְבָ֖ךְ תִּנְדַּֽע׃

But as for me, this mystery was not revealed to me because of any wisdom that I have more than any other living person, but for the cause that (לָהֵ֗ן עַל־דִּבְרַת֙ דִּ֤י) the interpretation may be made known to the king, and that you may understand the thoughts of your heart. — Dan. 2:30

The word here is דִּבְרַת֙ dibrat, which is the construct form of דִּבְרָה dibrah — reason, cause, manner, order. This word, like רַעְיוֺן explored in the previous entry, is used three crucial times in Ecclesiastes.

The first example, according to its function in the sentence, refers to the cause or propellant of the sons of men:

אָמַרְתִּי אֲנִי בְּלִבִּי עַל־דִּבְרַת בְּנֵי הָאָדָם לְבָרָם הָאֱלֹהִים וְלִרְאוֹתשְׁהֶם־בְּהֵמָה הֵמָּה לָהֶם

I said in my own heart concerning the cause (דִּבְרַת) of the sons of man, that God might purify them, and that they may see that they are themselves animals. — Ecc. 3:18

The second connotes God’s reason or purpose for his action:

בְּיוֹם טוֹבָה הֱיֵה בְטוֹב וּבְיוֹם רָעָה רְאֵה גַּם אֶת־זֶה לְעֻמַּת־זֶה עָשָׂההָאֱלֹהִים עַל־דִּבְרַת שֶׁלֹּא יִמְצָא הָאָדָם אַחֲרָיו מְאוּמָה׃

In the good day be in the good, and in the evil day see also this: God has appointed one against another for the cause (דִּבְרַת) of the man discovering that there is nothing after him. — Ecc. 7:14

The third is tied directly to God’s authoritative words:

אֲנִי פִּי־מֶלֶךְ שְׁמוֹר וְעַל דִּבְרַת שְׁבוּעַת אֱלֹהִים

I say, keep the king’s commandment (lit. mouth) for the cause (דִּבְרַת) of your oath to God. — Ecc. 8:2

It is also famously used in Psalm 110 regarding the priesthood of Melchizedek. In this case, it seems to function more in the sense of “manner” or “order”, after the LXX and NT rendering as τάξιν taxin:

נִשְׁבַּע יְהוָה וְלֹא יִנָּחֵם אַתָּה־כֹהֵן לְעוֹלָם עַל־דִּבְרָתִי מַלְכִּי־צֶדֶק

Yahweh has worn and will not relent, You are a priest unto the ages after the Order (דִּבְרָתִי) of Melchizedek. — Ps. 110:4

The itinerary of this root is so important because it highlights the overarching function of ד-ב-ר in the realm of God’s providence and his pastoral command over the sky and the land. The link to providence is firmly established in the Qur’an, where it has a wide semantic range from providence (10:3) to its most common function as “following with respect” as we find it in surah 4:

أَفَلَا يَتَدَبَّرُونَ ٱلْقُرْءَانَ وَلَوْ كَانَ مِنْ عِندِ غَيْرِ ٱللَّهِ لَوَجَدُوا۟ فِيهِ ٱخْتِلَـٰفًا كَثِيرًا

Why do they not follow ( يَتَدَبَّرُون from د ب ر) the recitation? If it were from any other than God, they would have found it with much inconsistency. — Q. 4:82

In the Qur’an, it can also refer to “turning one’s back” on something or someone, thus displaying a change of allegiance. In many cases, it is God causing particular groups to turn away. In other cases, there are commands for the believers not to turn their backs away from the revelation.

يَـٰقَوْمِ ٱدْخُلُوا۟ ٱلْأَرْضَ ٱلْمُقَدَّسَةَ ٱلَّتِى كَتَبَ ٱللَّـهُ لَكُمْ وَلَا تَرْتَدُّوا۟ عَلَىٰٓ أَدْبَارِكُمْ فَتَنقَلِبُوا۟ خَـٰسِرِينَ

O my people, enter the Holy Land which God has prescribed for you, and turn not back in your traces, to turn (أَدْبَارِكُمْ)about losers. — Q. 5:21

This root is firmly about movement, following, and leading depending on how it’s being used. It is inherently pastoral. No wonder the authors of scripture called the wilderness the מדבר midbar from דבר. They associate the Syrian desert with the Bedouins who inhabited it, and led their flocks by their voices.

But what of this use of דברה in the feminine? This is its orientation in Hebrew with the specific function of “cause”. This is interesting because it is consonantally identical with the character דְבוֹרָה debōrah, the judge and prophetess for the Israelites. Her name is often glossed as “bee”, from the exact same consonants in Hebrew.

סַבּוּנִי כִדְבוֹרִים דֹּעֲכוּ כְּאֵשׁ קוֹצִים בְּשֵׁם יְהוָה כִּי אֲמִילַם

They surround me like bees (כִדְבוֹרִים). They were quenched like a fire of thorns.

For in the name of Yahweh I will destroy them. — Ps. 118:12

This is likely related to the vocalization of דבר as “pestilence” as is found routinely in the book of Exodus.

וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֱלֹהֵי הָעִבְרִים נִקְרָא עָלֵינוּ נֵלֲכָה נָּא דֶּרֶךְ שְׁלֹשֶׁת יָמִים בַּמִּדְבָּרוְנִזְבְּחָה לַיהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ פֶּן־יִפְגָּעֵנוּ בַּדֶּבֶר אוֹ בֶחָרֶב

So they said, ‘The God of the Hebrews has met with us. Please, let us go three days’ journey into the desert and sacrifice to Yahweh our God, lest He fall upon us with pestilence (דֶּבֶר) or with the sword.’ — Ex. 5:3

It might also be worth mentioning that in form III of the Arabic verb for this root, دابر, refers to complete destruction, down to the root.

فَقُطِعَ دَابِرُ ٱلْقَوْمِ ٱلَّذِينَ ظَلَمُوا۟ وَٱلْحَمْدُ لِلَّـهِ رَبِّ ٱلْعَـٰلَمِينَ

So the last remnant of the people who did evil was cut off ( دَابِر). Praise belongs to God the Lord of all Ages. — Q. 6:45

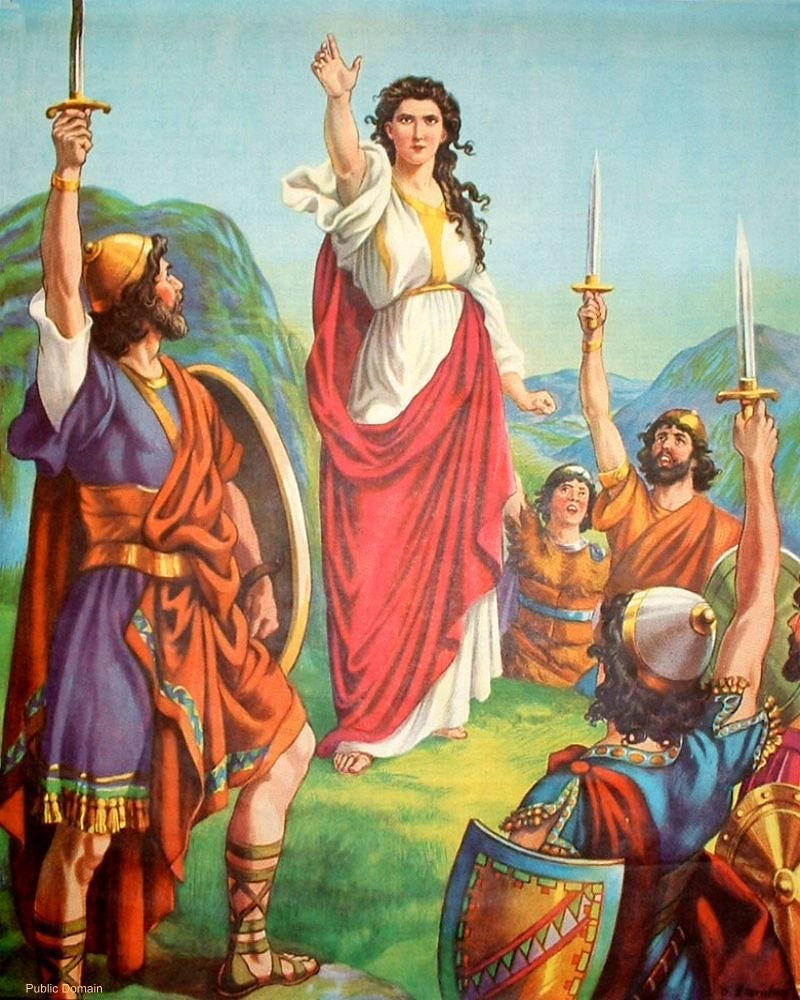

Deborah is characterized in the text as being a source for the Israelites to receive directions from God. She exercises this role under the palm tree! In other words, she is like a Bedouin poet!

וְהִיא יוֹשֶׁבֶת תַּחַת־תֹּמֶר דְּבוֹרָה בֵּין הָרָמָה וּבֵין בֵּית־אֵל בְּהַר אֶפְרָיִם וַיַּעֲלוּ אֵלֶיהָ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לַמִּשְׁפָּט

And Deborah would sit under the palm tree between Ramah and between the House of God, on the mount of Ephraim. And the Israelites went up to her for judgement. — Jdg. 4:5

From there, she exhorts her comrade Baraq (lit. “lightning” in Hebrew), commanding him to accept God’s providential hand in battle.

וַתֹּאמֶר דְּבֹרָה אֶל־בָּרָק קוּם כִּי זֶה הַיּוֹם אֲשֶׁר נָתַן יְהוָה אֶת־סִיסְרָא בְּיָדֶךָ הֲלֹא יְהוָה יָצָא לְפָנֶיךָ וַיֵּרֶד בָּרָק מֵהַר תָּבוֹר וַעֲשֶׂרֶת אֲלָפִים אִישׁ אַחֲרָיו

And Deborah said to Baraq, ‘arise! For this is the day that Yahweh has given Sisera into your hand. Has not Yahweh gone out before you? So Baraq went down from Mount Tabor; ten thousand men after him’. — Jdg. 4:14

It all comes together with the song of Deborah and Baraq in Judges 5, where the text uses highly poetic language that scholars have tied to archaic forms of Ugaritic poetry. In this sense it is very similar to the song of Moses in Exodus 15, which also uses archaic forms of Northwest Semitic poetry. But in this song of Deborah, the wordplay with her name is clearly highlighted.

עוּרִי עוּרִי דְּבוֹרָה עוּרִי עוּרִי דַּבְּרִי־שִׁיר קוּם בָּרָק וּשֲׁבֵה שֶׁבְיְךָ בֶּן־אֲבִינֹעַם

Awake, awake Deborah! Awake, awake utter (דַּבְּרִי) a song! Arise Baraq and lead captive your captives, o son of Abino‘am. — Jdg. 5:12

Deborah, as judge of Israel, reorients the Israelites from their own cause to the cause of God. That is the mechanism at play here. It is about what (and who) you follow, both in your intention and your behavior.

Excursus on the Sibylline Oracles (Persian & Jewish Anti-Hellenism)

I’d like to briefly discuss how the character of Deborah could be employed around a common literary mechanism of the Hellenistic period.

In Ancient Greece, there was a common trope in poetry that circled around a “Sibyl”. The sibyls were prophetesses, or “oracles”, who would impart the will of the deities to those who paid for their services. The name comes from σίοβολλα siobolla, the Doric equivalent of the Attic θεοβούλη theoboulē — divine counsel.

When Alexander expanded his influence throughout Southern Europe and Western Asia, there were several Sibylline poems written propagandizing his efforts. While many of these texts no longer exist, we know that they were prevalent. One of Alexander’s closest associates, the historian Callisthenes, remarked that Apollo of Didyma and the Erythrean Sibyl had prophesied Alexander’s coming kingship according to Strabo (book XVII, section 43). In his book on Near Eastern resistance to Hellenism, Samuel K. Eddy postulates that Persian elites began fighting back against this propaganda by crafting Sibylline oracles of their own (p 10). In fact, as he notes, Sibylline literature in Persia was known to Marcus Terentius Varro, the great Roman scholar contemporaneous with Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar.

Eddy finds his evidence in book III of the Sibylline Oracles, which seem to speak directly about Alexander’s conquest into Asia.

One day shall come to Asia’s wealthy land an unbelieving man,

Wearing on his shoulders a purple cloak,

Wild, despotic, fiery. He shall raise before himself

Flashing like lightning, and all Asia shall have an evil

Yoke, and the drenched earth shall drink in great slaughter.

But even so shall Hades care for him completely overthrown.

He shall be utterly destroyed by the race of the

Family he wishes utterly to destroy. — Book III, lines 388–395

That’s not to mention another section, not cited in Eddy’s book, from earlier in Book III:

And then shall Hellenes, proud and impure,

Then shall a Macedonian nation rule,

Great, shrewd, who as a fearful cloud of war

Shall come to mortals. But the God of heaven

Shall utterly destroy them from the depth. — Book III, lines 149–154

These sections square nicely with the dreams of Zarathustra and Nebuchadnezzar in the Bahman Yasht and book of Daniel respectively.

This apocalypticism runs deep during the Hellenistic period, especially in the 2nd century BCE where we also get the famous book of Enoch (commonly referred to as 1 Enoch). Many of the features of 1 Enoch reflect features in the Bahman Yasht, including the nature of their prophecies (Eddy 22).

The point in laying this out is to outline the brilliant repurposing of Hellenistic propaganda by Persian and Hebrew literature alike, by orienting it to the function of the unseen God who emits wisdom to his prophets — whether they be camel-herding priests like Zarathustra, or Bedouin poet warriors like Deborah, or exiled clerics like Ezekiel. When the King is dead, and the city has been destroyed, the temple desecrated, and the priesthood defunct… the priestly Torah is sent out on foot, to be a pedestrian Torah.

Deborah is the Hebrew sibyl, who does not take payment like the sibyls of the Hellenistic temples. And in fact, she doesn’t reside in a temple. She resides under the palm tree. It is there, in the open Syrian wilderness, that the Israelites come to her for instruction. No city is necessary, just the oracles of God.