When dealing with the origins of the Qur’an, many secular scholars of religion tend to work within the traditional narratives supplied by (predominantly) Sunni sources. This can include the Sirat Rasul Allah, a biography of Muḥammad written by Abbasid era hagiographer Ibn Isḥaq. Other sources include the Persian aḥadith collections purportedly preserving the sayings and practices of the Prophet. There are reasons to doubt these sources. For one, they appeared centuries after the Prophet’s death and within the context of the political rift following two internal civil wars (fitna) resulting in the permanent schism between those who sought leadership from the Prophet’s family (the Shi ‘as) and those who elected leaders deemed most competent to do so (the Sunnis). Likewise, both groups have their own sectarian collection of aḥadith conveniently supporting their own convictions. The scholars of the Islamic world did what the Jews and Christians did before them, despite being warned by the Qur’an itself to not break up into sects:

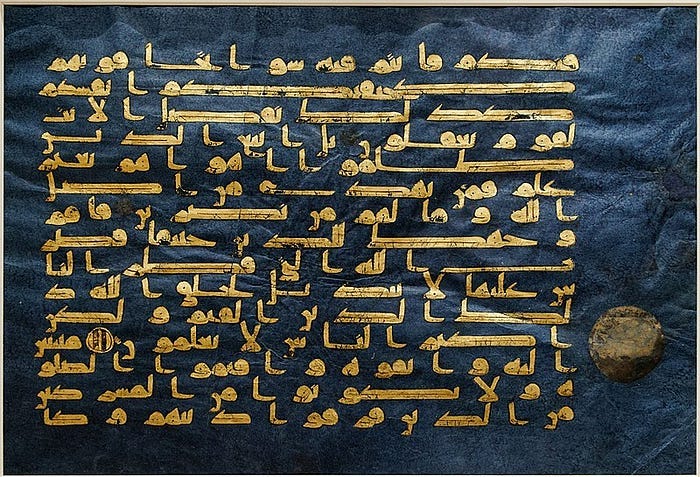

إِنَّ ٱلَّذِينَ فَرَّقُوا۟ دِينَهُمْ وَكَانُوا۟ شِيَعًا لَّسْتَ مِنْهُمْ فِى شَىْءٍ إِنَّمَآ أَمْرُهُمْ إِلَى ٱللَّـهِ ثُمَّ يُنَبِّئُهُم بِمَا كَانُوا۟ يَفْعَلُونَ

Surely you have nothing to do with those who have made divisions in their religion and become factions (شِيَعًا shi ‘an). Their matter is with God and He will indeed tell them what they have been doing. — Q. 6:159

And perhaps anticipating the reliance of these communities on their own concocted “narrations”, the Qur’an asks the following rhetorical question:

تِلْكَ ءَايَـٰتُ ٱللَّـهِ نَتْلُوهَا عَلَيْكَ بِٱلْحَقِّ فَبِأَىِّ حَدِيثٍۭ بَعْدَ ٱللَّـهِ وَءَايَـٰتِهِۦ يُؤْمِنُونَ

These are the proofs of God that we declare to you truthfully. Then in what narration (حَدِيثٍۭ ḥadith) after God and his proofs will they believe? — Q. 45:6

And also anticipating the inevitable failure of the Ummah to remain free from sects, the Qur’an chillingly forecasts Muḥammad testifying against his own people on Judgment Day.

وَقَالَ ٱلرَّسُولُ يَـٰرَبِّ إِنَّ قَوْمِى ٱتَّخَذُوا۟ هَـٰذَا ٱلْقُرْءَانَ مَهْجُورًا

And the Apostle will say: “O my Lord: my people took this Qur’an as a thing abandoned.” — Q. 25:30

This parallels Jesus’ testament against his followers outlined in surah 5:116.

If we are to treat the ḥadith literature as religious hagiography rather than history, what can we say about its origins? I think the answer is found both in the Qur’an itself, as well as contemporary witnesses of the Arab invasion of the Byzantine and Sassanid territories. Before continuing, it must be asked, why is this important? While I tend to be more focused on the literature itself, rather than its origins, I have found that properly understanding the historical context of a massive literature such as this is critical to hearing what it has to say. The fact of the matter is that the Qur’an was revealed during incredibly tumultuous times. I have outlined this before in two previous articles, one on surah 5 and another one on the topic of the suffering servant in the Qur’an. Those, I feel, do an adequate job of setting the stage for my thesis.

Historical Context — Nisibis, the Greco-Persian War, and the ḥanfa Arabs

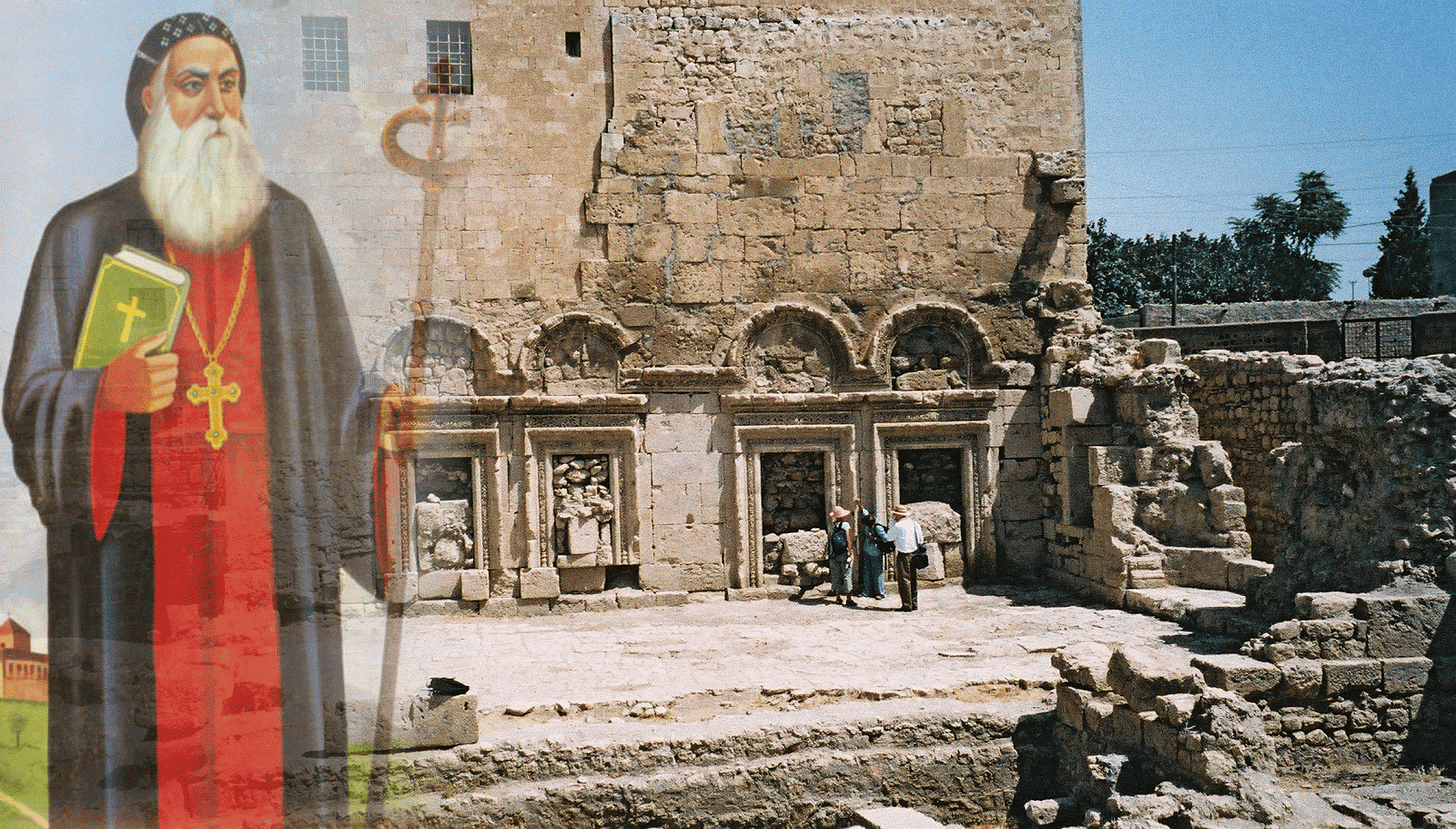

It was in the wake of the violent aftermath of the Christological controversies of the councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, which severely decimated any semblance of Christian unity in the East. This began as a dispute between two prominent bishops of the Eastern churches: Nestorius of Constantinople and Cyril of Alexandria. When the council finally met in 431, Nestorius was condemned as a heretic before he was even able to defend himself against the charge. He was promptly defrocked and excommunicated by the Byzantine bishops, and those who were loyal to him eventually fled to the Persian territories to avoid persecution. Today, the descendants of this community are known as the “Church of the East” or by modern scholars as “East Syriac”.

This community set up its headquarters in the Mesopotamian city of Nisibis (Nusaybin in the south of modern-day Türkiye), and founded an exegetical school based as a continuation of the Antiochene and Edessan schools, of which John Chrysostom, Theodore of Mopsuestia, Diodore of Tarsus, and Ephrem the Syrian were critical contributors. They were incredibly well-read in scripture, which I believe, conditioned the East Syriac Christians to respond “scripturally” to the later Arab invasion. The Persians also welcomed this community and supported it because they, like the so-called “Nestorian” Christians, were enemies of the Roman Empire. By the 7th century, the two massive empires were deadlocked in a devastating war that brought both powers to their knees.

Taking advantage of this weakened state, an organized militia of Arab tribes led by Muḥammad rapidly invaded territories spanning as far south as Egypt, up through Palestine and Syria, and even into Iraq and the Sassanid territories. While the Byzantines took a huge blow, the Persian Empire was completely finished by this raid. They were wholly unprepared for it. From the earliest Christian sources, the Arabs were simply brutal. From an anonymous West Syriac (miaphysite) witness circa 640:

There was a battle between the Romans and the Arabs of Muḥammad in Palestine, twelve miles east of Gaza. The Romans fled. They abandoned the patrician Bryrdn and the Arabs killed him. About four thousand poor villagers from Palestine — Christians, Jews, and Samaritans — were killed, and the Arabs destroyed the whole region.

Within a few years, the local Syriac Christians (East and West alike) began to interpret this invasion in apocalyptic terms. The Apocalypse of Pseudo-Ephrem is a prime example and even anticipates parts of the Qur’an. The thesis presented in this account is that the arrival of the Arabs was a punishment from God against the Byzantines for iniquity and heresy. The author accuses the Byzantines of “weighing down” the scales of justice, which calls to mind surah 55:7–9. The author also asserts that God will unleash the apocalyptic forces of Gog and Magog, who had been kept at bay by a wall set up by Alexander the Great (a reference to the Syriac Alexander legends). This same event is referenced in the Qur’an concerning Dhu al-Qarnayn and Ya’jūj and Ma’jūj in 18:94 and 21:96.

Even more intense is the Khuzistan Chronicle, written in the 660s by an East Syriac (Nestorian) author. Throughout the chronicle, he recounts that the Arabs destroyed everything in their path without mercy. By the end, he says something striking:

The victory of the Sons of Ishmael who overcame and subjugated these two kingdoms (Persia and Rome) was from God. Indeed, the victory is his. But God has not yet handed Constantinople over to them.

Perhaps the most critical piece of literature at this time is the monumental Book of Main Points written by the East Syriac monk John Bar Penkaye. Being well-read in scripture, he responded to this invasion scripturally. Unlike many of the miaphysite and Maronite responses, his response wasn’t just an indictment against his enemies — it was a scathing self-critique. For Bar Penkaye, God was not only punishing the Byzantines for their heresies, He was punishing all Christians including the church he belonged to. In his words, even the supposed “true faith” had grown so far from the basics of the faith, that if an early Christian martyr were to be transported to the present day they would not recognize the faith they gave their life for.

The westerners (miaphysites), it is true, clung tightly to their sacrilegious faith, but we who believe we adhere to the true faith, we were so far from the works of Christians, that if one of the former had risen and had seen us, he would have had been dizzy and said: “this is not the faith in which I died.

He traces this descent of Christianity with the continuance of fruitless controversies, forcing the church into endless scandal.

There were, indeed, many synods even before Nicaea, but they were not ecumenical, and were not convoked in order to make a new creed, but only for the purposes indicated indicated above. But once peace was restored and Christian kings had taken over the reins of government of the Romans, then vice and scandal entered the Church, and synods and sects multiplied, because every year someone invented a new creed. Security and peace led to many evils. The lovers of glory stirred up troubles unceasingly, using gold to obtain the consent of kings, so they could play about with them like little children. All this happened among the Romans.

As a response, God sent the Christians several signs that they were going astray but each one was unheeded.

Therefore when we were mixed up in every evil and all the impurities that we have mentioned, and God looked on and was saddened, and began to show mercy as usual, in order to excite our minds gradually to repentance. There were an earthquake in the city, but the hardness of our hearts saw them and was silent. He made signs appear in the sky, and our wicked nature saw them and did not take the hint. He sent grasshoppers and locusts that ravaged the fields and vineyards, and none of us wondered the cause of all this.

This lack of repentance, according to Bar Penkaye, led God to raise up the Arabs against them.

When he saw that there was no amendment, he raised a barbarian kingdom against us, a people who would not hear supplications, who knew no compromise, no peace, and disdained flattery and meanness. Its delight was in shedding blood without reason, and its pleasure laying hands on everything. Its passion was raiding and stealing, and its food hatred and anger; it was never appeased by offerings made to it. When it had prospered and done the will of Him who sent it, it had taken possession of all the kingdoms of the earth, had subjected brutally all the peoples and brought their sons and daughters into a bitter slavery, had avenged in them the opprobrium of God the Word, and the blood of the martyrs of Christ shed through no fault of their own, then our Lord was satisfied and rested, and He agreed to give grace to his people.

This reads very much like a prophetic oracle, right out of the Book of the Twelve in the Old Testament. If Bar Penkaye was one of those biblical prophets, Muḥammad would be Nebuchadnezzar or even Cyrus the Great. What is striking is that Bar Penkaye describes in detail both the leadership and internal conflicts among his oppressors. He is clearly writing during the reign of Mu’awiya I, amid the two successive civil wars among the Arabs. In all of this detail, he says nothing of their religion other than that they follow the traditions of their leader Muḥammad. There is nothing about the Qur’an, which is striking because Penkaye and others contemporaneous with him would have at least heard the adhan or would have encountered Qur’an inscriptions or recitations. Others around this time are also silent about any new holy text, or anything signaling a particular religion being brought over. The closest we get is a mention of the Arabs worshipping at a place called “The Dome of Abraham” in the aforementioned Khuzistan Chronicle.

And concerning the Dome of Abraham, we could not find out what it is except for this. Because the blessed Abraham had become rich in property and also wanted to be far from the Canaanites’ envy, he chose to dwell in the vast and distant parts of the desert. As a tent dweller, he built that place for God’s worship and the offering of sacrifices. Because the place’s memory had also been preserved by the clan’s descendents, it took its current name from what it had been. It is not new for the Arabs to worship there. Rather, from their beginning, from long ago they have worshipped therem paying honor to the forefather of their people. And Haṣur (Ḥebron), which scripture designates as “the capital”, is also the Arab’s. Theirs are also: Medina, which is named after the name of Midian, Abraham’s fourth son from Keturah.

These details, plus the political and religious climate, leads me to the thesis that the Qur’an was revealed, not in Mecca and Medina, but in northeastern Syria near the city of Nisibis, where its addresses — Arabs, Christians, Jews, Sabaeans, and Zoroastrians (Q. 17:22) — were found. It was the right place at the right time, where Christian monks like Penkaye were primed for its radical message (see 5:82–83) against sectarianism and total submission to the one God. Iraq was also home to a major center of Aramean Jewish scholarship, with much of the Talmud being compiled in Babylon. The Jews and Christians of the Persian Empire antagonized each other over the execution of Christ, which is directly put down in surah 4:154–158. To state the thesis in clearer terms, the Qur’an was revealed to the Arabs after the conquest and the two civil wars, not before. And it was just as much delivered to the Arab conquerors, as much as it was delivered to the various religious groups of the region. It was, for this reason, that the Qur’an was presented as a revelation in Arabic to Muḥammad in order for the two warring factions within the Umayyad Caliphate to learn the contents of the Torah and the Gospel and to be tamed by their teachings.

الٓر تِلْكَ ءَايَـٰتُ ٱلْكِتَـٰبِ ٱلْمُبِينِ إِنَّآ أَنزَلْنَـٰهُ قُرْءَٰنًا عَرَبِيًّا لَّعَلَّكُمْ تَعْقِلُونَ نَحْنُ نَقُصُّ عَلَيْكَ أَحْسَنَ ٱلْقَصَصِ بِمَآ أَوْحَيْنَآ إِلَيْكَ هَـٰذَا ٱلْقُرْءَانَ وَإِن كُنتَ مِن قَبْلِهِۦ لَمِنَ ٱلْغَـٰفِلِينَ

alif lām rā: Those are the proofs of the Clear Writ. We have sent it down as an Arabic recitation, that you might use reason. We relate to you the best of stories in what We have revealed to you of this Qur’an, though before it you were among those unaware. — Q. 12:1–3

The Arabs were also a people who highly regarded their poetry. Thus the Qur’an takes a jab at those poets.

وَمَا عَلَّمْنَـٰهُ ٱلشِّعْرَ وَمَا يَنۢبَغِى لَهُۥٓ إِنْ هُوَ إِلَّا ذِكْرٌ وَقُرْءَانٌ مُّبِينٌ

And We taught him not poetry, and nor is it fitting for him; it is only a remembrance and a clear recitation — Q. 36:69

It also embeds itself with an open challenge. If the Arabs doubt the Qur’an, they can bring forth one of their best poets to rival its words. Such an exercise is pointless because as 12:3 says, the Qur’an taught them what they did not know beforehand (ie the Torah and the Gospel).

وَإِن كُنتُمْ فِى رَيْبٍ مِّمَّا نَزَّلْنَا عَلَىٰ عَبْدِنَا فَأْتُوا۟ بِسُورَةٍ مِّن مِّثْلِهِۦ وَٱدْعُوا۟ شُهَدَآءَكُم مِّن دُونِ ٱللَّـهِ إِن كُنتُمْ صَـٰدِقِينَ

And if you are in doubt about what We have sent down upon Our servant, then bring a sūrah the like thereof; and call your witnesses other than God, if you be truthful. — Q. 2:23

While Muḥammad was long dead at this point, it was important for the Qur’an to have his “endorsement” so to speak as a key factor for the Arab leaders to take it seriously. In so doing, it keeps Muḥammad as under-stated as possible so that the Arabs do not turn their Apostle into an idol.

وَمَا مُحَمَّدٌ إِلَّا رَسُولٌ قَدْ خَلَتْ مِن قَبْلِهِ ٱلرُّسُلُ أَفَإِي۟ن مَّاتَ أَوْ قُتِلَ ٱنقَلَبْتُمْ عَلَىٰٓ أَعْقَـٰبِكُمْ وَمَن يَنقَلِبْ عَلَىٰ عَقِبَيْهِ فَلَن يَضُرَّ ٱللَّـهَ شَيْـًٔا وَسَيَجْزِى ٱللَّـهُ ٱلشَّـٰكِرِينَ

And Muḥammad is only an apostle; apostles have passed away before him. If then he dies or is killed, will you turn back on your heels? And he who turns back on his heels does no harm to God at all; and God will reward the grateful. — Q. 3:144

The Qur’an also discourages the Shi ‘ite obsession with Muḥammad’s family:

مَّا كَانَ مُحَمَّدٌ أَبَآ أَحَدٍ مِّن رِّجَالِكُمْ وَلَـٰكِن رَّسُولَ ٱللَّـهِ وَخَاتَمَ ٱلنَّبِيِّـۧنَ وَكَانَ ٱللَّـهُ بِكُلِّ شَىْءٍ عَلِيمًا

Muḥammad is not the father of any of your men, but the Apostle of God, and the seal of the prophets; and God is knowing of all things. — Q. 33:40

A comment like this makes the most sense if that were already a controversy, much like the sectarianism that Paul rebukes in 1 Corinthians 1:10.

Another clue as to the timeline is its mention of battles that God made the Arabs victorious in during their conquest. This closely parallels the apocalyptic literature of the Syriac Christians.

وَلَقَدْ نَصَرَكُمُ ٱللَّـهُ بِبَدْرٍ وَأَنتُمْ أَذِلَّةٌ فَٱتَّقُوا۟ ٱللَّـهَ لَعَلَّكُمْ تَشْكُرُونَ

And God had already helped you at Badr, when you were despised. Then be in prudent fear of God, that you might be grateful. — Q. 3:123

It also makes mention of the war between Byzantium and the Sassanids, which was viscerally in the memory of those in Iraq/Syria, right at the crossroads of Rome and Persia.

غُلِبَتِ ٱلرُّومُ فِىٓ أَدْنَى ٱلْأَرْضِ وَهُم مِّنۢ بَعْدِ غَلَبِهِمْ سَيَغْلِبُونَفِى بِضْعِ سِنِينَ لِلَّـهِ ٱلْأَمْرُ مِن قَبْلُ وَمِنۢ بَعْدُ وَيَوْمَئِذٍ يَفْرَحُ ٱلْمُؤْمِنُونَ

The Romans have been victorious. In the lowest earth; but they, after their defeat, will be victorious. — Q. 30:2–3

The Qur’an is clearly being revealed in an environment that is closer to these events and controversies. Of the intense Christological debates of Ephesus and Chalcedon, it says:

وَمِنَ ٱلَّذِينَ قَالُوٓا۟ إِنَّا نَصَـٰرَىٰٓ أَخَذْنَا مِيثَـٰقَهُمْ فَنَسُوا۟ حَظًّا مِّمَّا ذُكِّرُوا۟ بِهِۦ فَأَغْرَيْنَا بَيْنَهُمُ ٱلْعَدَاوَةَ وَٱلْبَغْضَآءَ إِلَىٰ يَوْمِ ٱلْقِيَـٰمَةِ وَسَوْفَ يُنَبِّئُهُمُ ٱللَّـهُ بِمَا كَانُوا۟ يَصْنَعُونَ

And among those who say: “We are Christians,” We took their agreement; then they forgot a portion of that they were reminded of. And We brought about among them enmity and hatred until the Day of Resurrection; and God will inform them of what they wrought. — Q. 5:14

From even a broad reading of the Qur’an, it is clear that its main message is anti-sectarianism and the simplicity of Abraham’s original submission to God. As one of its digs against the Jewish and Christian communities, it employs the adjective ḥanif to describe Abraham.

وَقَالُوا۟ كُونُوا۟ هُودًا أَوْ نَصَـٰرَىٰ تَهْتَدُوا۟ قُلْ بَلْ مِلَّةَ إِبْرَٰهِـۧمَ حَنِيفًا وَمَا كَانَ مِنَ ٱلْمُشْرِكِين

And they say: “Be such as hold to Judaism, or Christians — you will be guided.” Say: “Nay, the way of Abraham, was ḥanif; and he was not of the idolaters.” — Q. 2:135

This is particularly striking because the Jews and Christians used the Syro-Aramaic word ḥanfa from the same root to describe pagans. A more precise way to render it would be “heathen”. Calling him ḥanif is a way to say that he does not belong properly to either Judaism or Christianity (or even to Sunni and Shia Islam). Abraham was declared righteous before he was circumcised, as is argued by Paul in Galatians 3 and Romans 4. Despite Abraham being a pagan “ḥanfa”, he submitted himself to God and that becomes the model, not man-made religions.

As a means to outline the “Way of Abraham”, the Qur’an begins with a creed of its own in the form of al-Fatiḥa. Unlike the endless creeds of the Christian tradition, al-Fatiḥa is a declaration of Abraham’s faith, something the Christians, Jews, and Sabaeans accepted without issue. It is simply a statement of allegiance to God and him alone, and a prayer that he blesses those who he guides on the straight path. After that creed, we enter into the second surah of the Qur’an which opens like so:

الٓمٓ ذَٰلِكَ ٱلْكِتَـٰبُ لَا رَيْبَ فِيهِ هُدًى لِّلْمُتَّقِينَ

alif lām mīm: That is the Writ about which there is no dispute, a guidance to the righteous. — Q. 2:1–2

The use of the word رَيْبَ rib is striking because that root in the Hebrew Bible is commonly used to describe fierce contention. It is something that one disputes in a legal court, or perhaps here, in an ecumenical council. The Qur’an is offering its audience a clear creedal statement that cuts the fat, and goes straight for Abraham’s faith, which is what the Jews and Christians ultimately rest on. In one fell swoop, it offers this creed as something novel to the Arabs but as a remembrance to the Jews and Christians who have gradually lost sight of it. But, as there is nothing new under the sun, the Qur’an was simply co-opted by the Shi ‘as and the Sunnis and they continued on following their traditions of men. But what is written stands as a testimony against them and us, and now that it has been written none of us have an excuse to ignore it. This is true for Jews who have the Torah, Christians who have the Gospel, and Muslims who now have the Qur’an.

Further Reading:

When Christians Met Muslims — Michael Philip Penn

The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Qur’an — Christoph Luxenberg

The Silk Roads — Peter Frankopan

The Qur’an in its Historical Context — Gabriel Said Reynolds

St. Cyril and the Christological Controversy — John McGuckin