What Would Superman Do? — Review of the Latest Film

Last night, I decided to watch James Dunn’s Superman expecting to see a nostalgic return to form. I absolutely love the first two Donner films, as well as their spiritual sequel, Superman Returns. I could feel this old school tone immediately, with the welcome return of John Williams’s classic score, as well as those 70s title cards. I purposely refrained from looking at reactions online, so I wasn’t expecting how prominent the genocide in Gaza was in the film. I guess it’s my cynicism, but I’m just trained to expect Hollywood to ignore what’s going on over there. Israel is such a touchy subject in those circles. I remember when Jonathan Glazer, the director of The Zone of Interest, was called a “self-hating Jew” when he spoke out against the abuse of the Israeli government against Palestinians. His film was about the Holocaust, and his message was that detachment from the humanity of the “other” is what allowed the Holocaust to occur in plain sight. It happens when people just look the other way. Kind of how Hollywood has, thus far, treated the genocide in Gaza. It is another Holocaust.

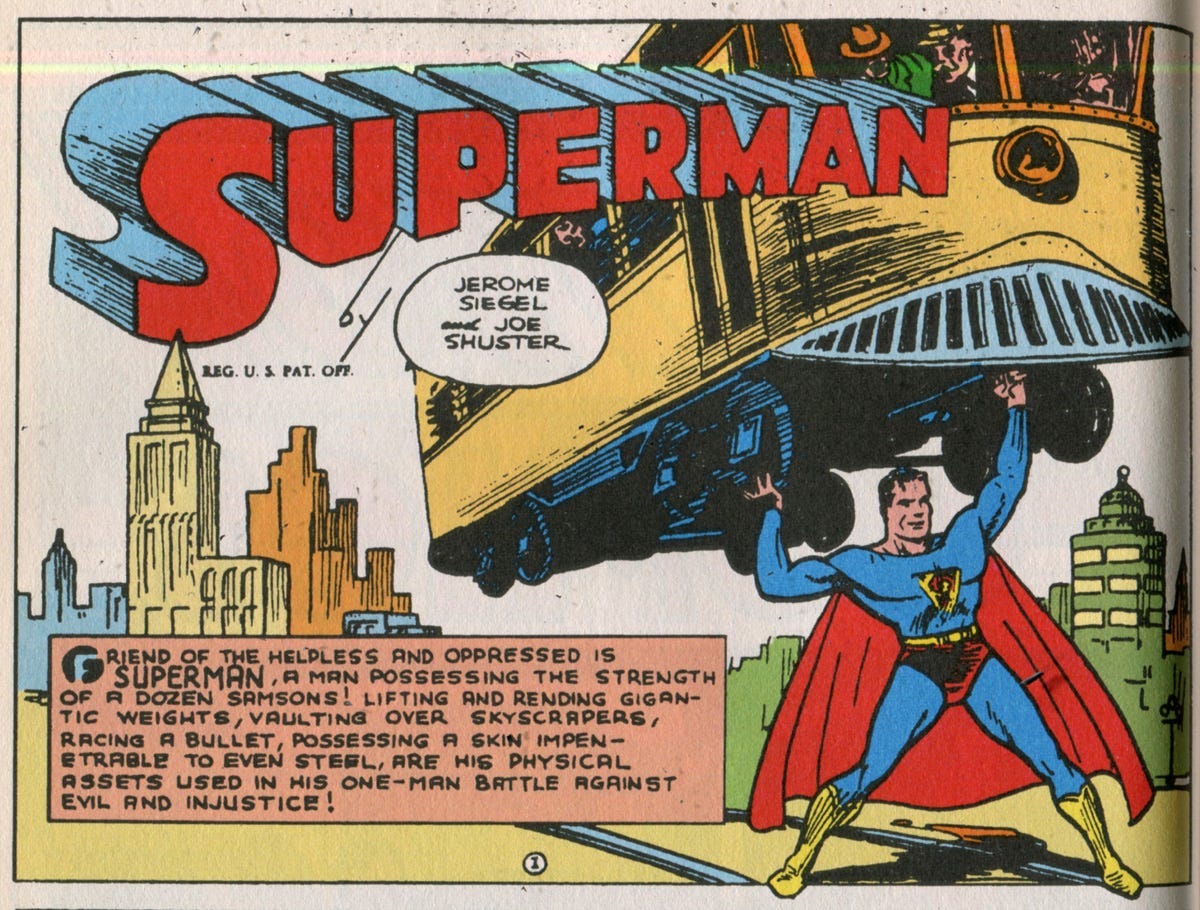

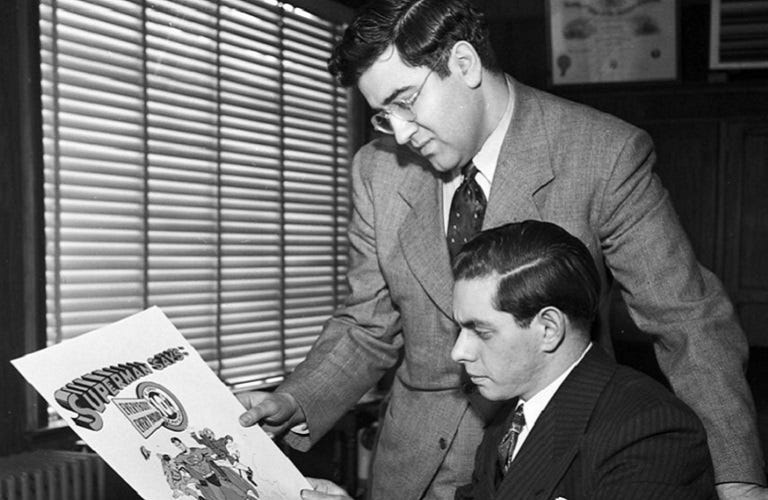

But that’s where a Superman film in the wake of October 7, 2023 is a critical opportunity. The character Superman was created in the mid-1930s by author Jerry Siegel and illustrator Joe Shuster.

A lot of people have talked about the idea of Siegel and Shuster reflecting their experience as Jewish immigrants into the character. I think sometimes this can be a problematic assumption, as if Jewish artists are bound to put Jewish themes into their work. People often pin Stanley Kubrick like that, as if he wanted to make especially Jewish films. My read of Kubrick’s own words is that he precisely tried to avoid that stereotype. He didn't want his films to be read as specifically “Jewish” stories. I think Siegel and Shuster were similar in that regard. They wanted to create an American superhero. But at the same time, Superman is an outsider, and his main objective was to be a champion of the oppressed. I think for that reason, many Jews throughout history have identified with that message. The original Superman stories were released at the height of anti-semitism in Europe. This naturally fueled a new wave of immigration to the United States, which had already been strong since the end of the 19th century. What followed was the cross-road that any immigrant from a traditional culture faces in the “melting-pot” of the United States. Do we keep our traditions and identity from back home, or do we fit in?

One of my favorite films is The Jazz Singer (1927) with Al Jolson. That film is famous primarily for it being considered the first “talky”, which isn’t even really true. There’s only a handful of scenes with synchronized sound. The rest of it is just like any other silent film of the twenties. But that being said, what is less discussed, but more powerful is the fact that it is a film about a young Jewish cantor who wrestles between his traditional culture and his love of American Jazz music. Naturally this puts him at odds with his family and synagogue. It likewise causes issues with his broadway producers, who essentially want him to reject where he came from and melt like everyone else. But at the end, he realizes he doesn’t need to choose. He doesn’t need to melt in the melting pot in order to exist in New York and have the career he wants. He can be an American and be Jewish. One doesn’t have to dominate the other. It’s a beautiful film.

I think Superman represents this tension. He’s an outsider who really doesn’t melt in his original incarnation. Sure, there’s Clark Kent. But Clark is only a mask that he uses in his professional life at the Daily Planet. It doesn’t erase the fact that he is Kryptonian. In fact the most important work he does is as his real self, as Kal-El, and he becomes the “friend of the helpless and the oppressed”. In the 1930s and 40s this could represent a ton of people, as it does today. Superman was the great “anti-nazi” force. In the same way, he was against the melting pot. He used where he came from to better the place where he arrived, in a way only a Kryptonian could. This is the value, not of the “melting pot”, but of an eclectic settlement on the same land. It is an anti-nationalist statement. Superman is about co-existence. It is Lex Luthor, the business mogul, who seeks to strike fear against Superman as the “other”. He represents institutional control, seeking to enforce the melting pot. Nationalism often demands homogeneity. Superman, as the ultimate alien, contradicts that notion. He proves difference can be a gift, not a threat. Luthor’s fear-mongering is an echo of the demagogues who paint immigrants and minorities as existential threats. This is the brilliance of Siegel and Shuster’s original story. I don’t think, for them, it’s specifically Jewish. But it was definitely the kind of story that Jews, and other immigrants, could latch on to. It was their experience. In that sense, and only that sense I feel, is Superman a Jewish story.

But that leads us to today, and the modern rendition of Superman. I was particularly touched by that question that permeated the film: what would Superman do about Gaza? The answer is simple and obvious. He would fly in and protect the children, even going against his own government to do so. Since the 1950s, Superman has acted as an agent for the “American Way”. This is a bastardization of his character. He’s not an American nationalist. He is a champion for justice globally. The American government in the film works in tandem with Lex Luthor’s fear mongering and corporate exploitation. They also back the country Boravia, an obvious stand in for Israel. For much of the film, Superman is maligned as a dangerous supporter of terrorists — something that those who speak out against Israel’s genocide often face. One key moment is a startling revelation that Kal-El’s parents recommended that he use his strength to conquer the human race. Luthor airs this to the world. It touches on something that Jews and Arabs experience all the time. Conspiracy theories about Jews controlling everything, and all being Zionists as if they are a monolithic group without individuality. There’s also the idea of there being Arab and Muslim sleeper cells in the United States, just waiting for the opportunity to commit 9/11 2.0.

In one of the film’s most touching scenes, Kal-El’s adoptive father tells him that it is his actions that define him, not his identity. While this on its own is a bit cliche, given that super hero movies tend to have this Uncle Ben style “great power, great responsibility” speech, it still touches on a challenge the film is offering to its viewers. Many people consider anti-Zionism to be “anti-semitism”. Some Jews feel threatened by it. On the one hand, it’s understandable. The trauma of the Jewish experience in Europe is insurmountable. But at the same time, the establishment of the state of Israel created its own trauma against the people who were already living there. It took the trauma of the Holocaust and European anti-semitism and created a new Holocaust, 80 years in the making. It’s not about who suffers more or harder. Both the Jews and the Palestinians have been victims of hyper-nationalism and colonialism, and both have faced genocidal erasure.

I hope this film helps steer the conversation away from allegations of anti-semitism and other nationalist fear-mongering. I hope it calls all of its viewers, no matter where they come from, to see a common humanity. Modern Jewish commentators like Noam Chomsky, Shlomo Sand, Norman Finkelstein, Seymour Hersh, and Jay Shapiro — just to name a few — are courageous representatives breaking the stereotype that Jews must be Zionists. They actually learned from the horrors of the Holocaust to speak out against it when they see it happening again in real time. It is so powerful that James Gunn’s Superman had the heart to stand with that crowd. History will remember.

L’Chaim ve Ahavath Achim.