Continuing my recent work on lexicography, I would like to explain why this discipline is desperately needed for Biblical and Qur’anic studies. I have come to not only see its practical value but also its necessity (see my paper on the subject). While the discipline of lexicography is useful in any language, Semitic languages deserve special attention because of their dynamic utility with consonants and consonantal structures. This is not only a feature of Semitic languages, but actually, their broader Afro-Asiatic family spanning from East Africa to Mesopotamia.

To put this in simple terms, languages communicate meaning by two means: inflected and analytic expression. Most fall on a spectrum, but many lean towards one expression over the other. Afro-Asiatic languages, in contrast to Indo-European ones, lean heavily towards the former. What is the difference? Let’s look at an example from Hebrew.

We begin with the basic structure of Hebrew vocabulary which is centered on a template of three consonants. For example, we could have the function ש-ב-ר ( šin-bet-resh). This root points to a range of lexical values (everything from brokenness to desolation) that can be specified only by how the verb is inflected. The simple inflection of the verb is שָׁבַר šabar — he broke. If we wanted to intensify the action by saying he “shattered” something, we would inflect the vowels as such: שִׁבֵּר šibber — he shattered/ smashed. Where in English, we had to change the verb from “break” to “shatter”, Hebrew can communicate both functions from the same root, just inflected differently. If I wanted to communicate that someone caused something to break, I would say הִשְׁבִּיר hišbir — he caused to break. This is where English takes after a more “analytic” expression. Meaning is conveyed via helping words (i.e. caused to break) and different, more specialized vocabulary (i.e. shattered) whereas inflected languages pack layers of meaning into a single word with remarkable efficiency. Hebrew has seven binyanim (verbal forms) on top of the routine verbal conjugations in two aspects, perfect and imperfect. Likewise, all of these roots have nouns and participles that coorespond to the verbs. For example, שֶׁבֶר šeber — destruction appears in Jeremiah 6:1. As a participle, we have the phrase קָרֹ֣וב יְ֭הוָה לְנִשְׁבְּרֵי־לֵ֑ב qarob yahweh lenišberey leb — Yahweh is near to the broken hearted. We also have examples such as Psalm 42:7 which uses the nominalized form מִשְׁבָּרֶ֥יךָ mišbareka — your waves. Here, even the word “wave” (in Hebrew, literally a breaking of the waters) is connected with this root. Therefore, we as students of Hebrew must submit to this reality where vocabulary does not have “meaning” per se, but different (albeit related) functions depending on what the lexical item is doing in a particular environment. I opt for itinerary rather than context because “context” can be misapplied by the reader. If we think of these words having an itinerary, we are forced to stick the activity of the word, rather than its supposed essential definition.

For this reason, dictionaries often do a disservice to students of scripture. They place a higher importance to lexical value rather than the itinerary of a given consonantal construction. Such dictionaries will treat words like שֶׁבֶר and שִׁבְרוֹן as different words, despite being from the same root. This results in unnecessary confusion especially when a form of the root acts in a way that is contrary to its typical function. A clear example of this is the oft misunderstood word חֶסֶד ḥesed typically rendered as “steadfast love”. This is complicated when a Hebrew student comes across Leviticus 20:17 and finds that חֶ֣סֶד ḥesed functions there as a “wicked” or “shameful” thing. Does that word mean love or shame? Neither. Meaning is arbitrary! What matters is the word’s function. Someone familiar with Arabic will understand this, because the same root (ḥ-s-d) often has a negative connotation as indicative of “envy”.

Thus, it is imperative to study Semitic languages with their consonantal structures in mind.

Another difficulty that complicates the study of Hebrew is an over-reliance on the Masoretic vocalizations, which were embedded into the manuscript tradition by medieval rabbis to standardize cantillation. European scholars have greatly abused this feature and tend to treat the vocalizations as “vowels” instead of useful diacritics for reading. THE DIACRITICS ARE NOT VOWELS. We must remember that vowels don’t really exist in Hebrew; the sound between consonants are merely inflected for emphasis. Diacritics do not constitute their own letter, and are meant only to aid the reader instead of being ipso facto native to the text. An example from Koine Greek would be the use of diacritics in scholarly editions of the Greek New Testament which are all but ignored completely in Modern Greek (as are vowel diacritics omitted in Modern Hebrew publications). One has such diacritics as the hard (‘) and soft (’)breathing marks that differentiate the nominative- feminine-singular-definite article ἡ (pronounced hē w/ the rough breathing) and the subjunctive third person singular form of εἰμί eimi — to be in the dative ᾖ (pronounced ē w/o the rough breathing). These diacritics are not native to the original manuscripts and are merely there for convenience. To treat these diacritics as their own consonants is just as ludicrous as to treat the Hebrew vocular diacritics as vowels.

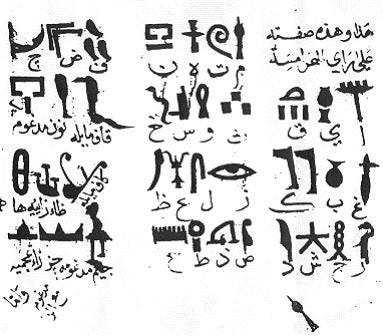

We have to submit to the fact that we are dealing with a consonantal text, where the vowels are not only secondary but perhaps even tertiary to the matter at hand. So unimportant were they, like the rough and soft breathing for the Greeks, that the Phoenicians didn’t bother to include vowels in their abjad. It simply didn’t fit the consonantal structure of their language. Not only them, but the Egyptians also had a semi-phonetic writing system that was purely consonantal due to this shared feature of the Afro-Asiatic family, of which Semitic languages are only a part. Like their Afro-Asiatic counterparts, the Egyptians did not see a reason to include vowels in their script.

If vowels were not necessary for them, we should not see them as a missing component in the consonantal text of the Bible. While it certainly takes more work, we should pay far more attention to the consonantal root than any other lexical feature. Even when the grammar points to a specific orientation of the word’s function, we can’t gloss over the broader matrices in any given root. Another example would be the verb לָחַם laḥam — to fight which shares its triliteral root with לֶחֶם leḥem — bread. This can throw students off until you realize that לָחַם can also be used to communicate being devoured or consumed (as one does with eating and fighting), which can be demonstrated by verses like Deuteronomy 32:24. In Arabic, لَحَّام laḥām can refer to either a butcher or a welder, interestingly covering both food and blacksmithing. Instead of “bread” specifically, لحم laḥm properly means “meat”, evoking the butcher and violence carried out with fighting. This could clue us into the functionality of the famous בֵּית לֶחֶם beit leḥem in scripture which is commonly thought of as the house of bread, especially given the vocalization. Without the vocalization though, we could just as easily treat it as the house of devouring, or the house of fighting/ violence. Judges 5:8 uses לָחֶ֣ם laḥem as “war” which is consonantally identical to לֶחֶם. This could shed light to the choice of the biblical authors to set David’s origins in Bethlehem. It adds an unsettling layer to the story, especially given David’s intense life of violence once he becomes king. Bethlehem is not necessarily good news, despite Jews and Christians taking pride in the city because of David’s and Jesus’ origins respectively. In scripture לחם can either be nourishing or destructive depending on its particular itinerary. There is no essentialism in consonantal literature. A translation could never communicate the link between bread and violence.

In this, we must take the prologue to the book of Sirach with utmost seriousness:

παρακέκλησθε οὖν μετ᾿ εὐνοίας καὶ προσοχῆς τὴν ἀνάγνωσιν ποιεῖσθαι καὶ συγγνώμην ἔχειν ἐφ᾿ οἷς ἂν δοκῶμεν τῶν κατὰ τὴν ἑρμηνείαν πεφιλοπονημένων τισὶ τῶν λέξεων ἀδυναμεῖν· οὐ γὰρ ἰσοδυναμεῖ αὐτὰ ἐν ἑαυτοῖς ἑβραϊστὶ λεγόμενα καὶ ὅταν μεταχθῇ εἰς ἑτέραν γλῶσσαν. οὐ μόνον δὲ ταῦτα, ἀλλὰ καὶ αὐτὸς ὁ νόμος καὶ αἱ προφητεῖαι καὶ τὰ λοιπὰ τῶν βιβλίων οὐ μικρὰν ἔχει τὴν διαφορὰν ἐν ἑαυτοῖς λεγόμενα.

Wherefore let me intreat you to read it with favour and attention, and to pardon us, wherein we may seem to come short of some words, which we have laboured to interpret. For the same things uttered in Hebrew, and translated into another tongue, have not the same force in them: and not only these things, but the law itself, and the prophets, and the rest of the books, have no small difference, when they are spoken in their own language.

Here is a translation that is up front and honest about its inadequecy. How can you render a consonantal language into an analytical one like Greek? This warning from the grandson of Sirach underscores the importance of the original in getting the accurate elements, whereas translations always serve as an approximation (or in this case, an invitation).

SCRIPTURE IS WRITTEN IN CONSONANTAL SEMITIC AND (SEMITICIZED) KOINE GREEK. EVERYTHING ELSE IS NOT SCRIPTURE!